HYDERABAD: 36-24-36—these are not just numbers, they are considered as standardised measurements of a model in the fashion industry; they represent the so-called ideal figures for women. But let’s not forget that whoever created us — human beings — didn’t set us up with parameters like these.

We all come in different sizes, shapes, and colours. Even though we know these beauty standards don’t align with reality, society still pushes these unrealistic ideals on women, which has a real impact on their mental health across generations.

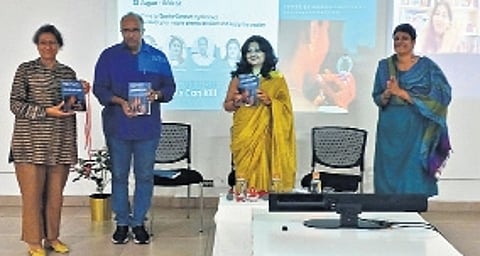

Underlining this very issue, Srirupa Chatterjee, Associate Professor of English, Body Image, and Gender Studies and Head at the Department of Liberal Arts at IIT Hyderabad and Shweta Rao Garg, an artist, poet, author and academic have come forward with their new edit, ‘Female Body Image and Beauty Politics in Contemporary Indian Literature and Culture’, a book published by Temple University Press.

Launched recently at the Goethe-Zentrum, this book takes a closer look at the influence of these beauty standards and explores their representation in contemporary Indian literature and culture.

What is the central theme and what inspired you to write this book?

Srirupa Chatterjee: The central theme of the book is how the dominant standards of beauty impact Indian women across ages, ethnicities, classes, communities, and regions. It’s not just a one-time thing; it’s almost like from the moment a girl is born until she grows old, she’s constantly reminded of how she looks. And while we acknowledge in the book that appearance bias affects everyone—across genders, sexual identities, body types, and so on—it’s women who tend to face the brunt of this discrimination. This is something women worldwide experience, but as Indian women, we face some very specific challenges regarding appearance discrimination. That’s really where this whole idea started.

For me, this understanding grew through my studies of feminist literature during my undergraduate and postgraduate years, and later in my PhD. I noticed that in the Western world, feminists were strongly addressing and discussing body image issues. But in India, while psychologists, anthropologists, and even medical practitioners and plastic surgeons had talked about appearance discrimination, there wasn’t really a cultural movement around it. We’ve had sporadic efforts—like the Dove campaigns, the ‘Dark is Beautiful’ campaign etc but there wasn’t a unified voice. Indian feminists did talk about it in certain spaces and moments, but perhaps it wasn’t seen as a strong enough issue to engage with fully. This is where we felt our intervention was crucial because this issue is so close to all of us, yet it’s rarely articulated, probably out of fear and shame.

You explored many topics like literature, culture, cinema etc. How did you navigate through these topics?

Srirupa Chatterjee: We wanted to cover a wide range because India is incredibly diverse, and there’s no single category that defines ‘the Indian woman’. So, we aimed to articulate as many body image concerns as we could. We decided to start with the voices that are often unheard and the most marginalised. That’s why we began with a chapter on Tamil Dalit women, exploring their experiences with body image, hygiene, shame, and social acceptability.

Next, we moved on to narratives from trans and lesbian women, who often feel ashamed to talk about how their bodies are perceived. Even when they embrace alternative sexual identities, there’s still this underlying pressure to conform to some idea of what’s ‘ideal’.

We chose to focus initially on literary engagements and then gradually expanded to culture in general—covering films, advertisements, popular media, and even magazines. We wanted to give voice to as many issues as possible. Of course, there’s so much more that needs to be addressed, but we felt this brought together certain key issues that needed attention.

In what ways do you think the beauty narrative affects women’s self-perception and mental health in India?

Shweta Rao Garg: One thing is that you’re constantly being judged, and when that happens, what’s external to you starts becoming internal. When something is repeated over and over, it starts affecting how you see yourself. When you realise there’s a deviation from the ‘ideal’ standard, especially regarding your body, it affects your confidence. Even if people say you’re beautiful, there’s still that fear that things will change.

Now, with post-liberalisation and the rise of social media, there’s constant pressure to look a certain way. People say things like ‘fair is beautiful’, but what does that really mean? Or ‘fat is beautiful’, but only within certain limits. Even ‘dark is beautiful’ comes with caveats. Everything is commodified in some way, and you end up working on your body to fit these paradigms. That’s what’s painful—you do this every day.

Srirupa Chatterjee: I mean, it really takes away from our natural abilities to be leaders, doers, agents of change in this world because so much of our effort, energy, and attention goes into maintaining our appearance. It’s a constant negotiation. I’m not saying that all women are victims — many do negotiate and come out successful — but we’re constantly reminded of this, and that’s something we can’t deny.

You mentioned the role of media and advertising in perpetuating body image standards in India? Can you mention any changes that you observed in recent years?

Srirupa Chatterjee: It’s actually really interesting, this whole body positivity movement. While there’s this growing effort to include plus-size models and feature a wider range of skin tones, there are still a lot of gaps. You see attempts to challenge things, like Dove’s campaigns that question traditional beauty standards. But at the end of the day, they’re still selling their own products. Instead of promoting fair skin, now it’s all about glowing skin. While the market might be accommodating different body types, it’s also making sure to profit even more from it. That’s one of the toughest issues to deal with. And that’s why this inclusivity doesn’t feel as genuine as it should.

How do you think the conversation around body image might evolve in the coming years in India?

Srirupa Chatterjee: The more advocacy we have, the better chance we have of making policymakers, educators, and media houses understand the importance of addressing body and appearance discrimination. This could lead to a healthier society where people feel comfortable with their bodies.

Maybe one day, education policies will include this in the curriculum to help people understand. We need sensitisation from all stakeholders — education, media, the internet, and even within families. I really believe that if there is a future where this discrimination is acknowledged, questioned, and slowly eliminated, we would have a healthier world when it comes to bodies and appearances.

Shweta Rao Garg: Another thing is at the individual level. For instance, when I’m talking to my family, I make it clear that I won’t participate in conversations where people comment on someone’s appearance. Of course, this goes beyond just personal interactions — it needs to happen at a larger level with schools, education policies, media, social media, everything, from the micro to the macro. That’s where the change needs to happen.

Can you highlight key takeaways from the book?

Shweta Rao Garg: One of the key takeaways is how different bodies experience beauty bias in different ways. We’ve inherited this colonial idea of a fair, slim, athletic body, but our own DNA often doesn’t align with that ideal because Indians are diverse. Every region in India has its own DNA coding — our bodies, skin tones, everything varies. It’s practically impossible for us to fit into a single ideal body image. Each essay in the book explores these challenges across different contexts and subcultures.

We also look at the body positivity movement, which, while it seems great and is growing, still feeds into a commodification culture. It’s like saying, ‘Big bodies are great’, but then implying you need to buy certain things to make your bigger body acceptable. So, inclusivity comes with exceptions, and while it might change in the future, right now, bodies still need to be ‘Instagram-worthy’.

That’s the problem with a scopophilic culture that focuses so much on visual glamour and the pleasure derived from it.