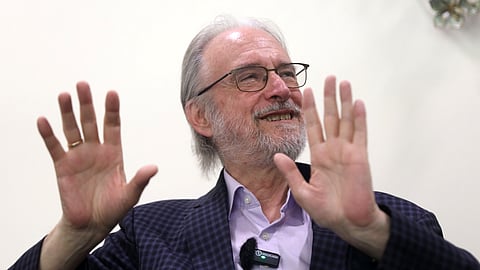

A visionary whose legacy hums through every playlist and podcast, Dr Karlheinz Brandenburg is the genius behind the MP3, a tiny file that sparked a massive revolution. His groundbreaking work didn’t just shrink audio files, it reshaped how the world listens to music, paving the way for pocket-sized players.

In an exclusive interview with Siddhardha Gattimi of TNIE, Dr Brandenburg shares his latest pursuit: the Immersive Audio Augmented Reality Headphone System, a cutting-edge solution to bring rich surround sound to those without access to expensive speaker setups.

Excerpts:

Where did the idea of compressing audio data so efficiently originate? Was there a specific moment or problem that sparked the concept of MP3?

The idea emerged in various parts of the world, but in our case, it began at Erlangen University. My thesis advisor, Dieter Seitzer — an expert in psychoacoustics — had worked on digital phone connections. He envisioned the equivalent to the introduction of black & white TV to phone networks by enabling not just speech but full-range music. He applied for a patent for that idea, but it was rejected as “impossible”. That’s when he approached me. I initially thought the examiner was right, but it would still make a good PhD topic. Turns out, I underestimated the idea completely (chuckles).

What was it like working on MP3 in the early days, especially when few people understood its potential?

It wasn’t easy. In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, public funding supported research into digital radio technologies. We were a part of a team led by Heinz Gerhäuser, competing with others. People told us our system was too complicated and unlikely to be used. But we stuck to our vision, and in the end, we succeeded.

You recently met music director MM Keeravani. Indian classical music uses microtones and complex rhythms. From a psychoacoustics standpoint, how does that impact compression and perception modeling?

Not at all. Unlike speech coding where generation of speech is crucial, audio compression aims to reproduce every sound. It’s all about how our ears work, and human hearing is largely consistent across cultures.

Did you face challenges compressing Indian classical music compared to Western music?

Not really. When judging audio quality, we found that people are most sensitive to subtle differences in the music they are familiar with. In our team, one member who loved hard rock was the only one who could hear certain distortions — others just heard noise. It’s likely the same with Indian classical music. Listeners may notice subtle differences more easily, but ultimately, the compression process works the same.

Q. Have you ever analysed Indian music specifically for MP3 compression?

In our team in Ilmenau (a town in Germany), we have a member who composes Indian-style music. We have used his work, though it sounds more like Western classical, as demo material for spatial audio. But we have not done specific experiments on Indian music.

Your recent work with the Immersive Audio Augmented Reality Headphone System is fascinating. Could you tell us how this technology works and where it can be helpful?

Yeah, immersive audio through headphones is something people have wanted for a long time, especially those who can’t install multiple speakers or play audio loudly. But many attempts overlooked how our brain processes sound. As we move, the sound reaching our ears changes constantly, and our brain interprets those changes to locate sound sources. Another key factor is reflections; rooms naturally have them, and we use them subconsciously, like bats, to understand our surroundings. By incorporating both movement and reflections, we can now create headphone experiences that feel realistic. That’s been a major breakthrough in recent years.

Has psychoacoustic research evolved since MP3? Could newer insights lead to better compression?

In two-channel audio compression, we have likely hit the ceiling — it’s limited by the ear biology. But with spatial or impressive audio, the real processing happens in the brain, and that’s still only partly understood. Over the past decade, we have made significant progress and immersive sound is now more realistic than ever. Still, I believe there’s room for improvement as we continue learning how the brain interprets complex sound environments.

Do you think the MP3 format is nearing its end with newer codecs like AAC (Advanced Audio Coding) or Opus becoming more common?

It’s easy for me to recommend AAC as we were involved in its development too. While I worked more directly on MP3, I also had a strong influence on AAC, along with our team. AAC is clearly better than MP3 in several ways. Having said that, MP3 is still widely supported and will continue to be around for a long time. Most devices today can handle multiple formats, so MP3 isn’t going away anytime soon.

AI is being used in spatial acoustics for VR and gaming. What’s your take on AI’s role in shaping audio experiences?

At Brandenburg Labs, we’re currently exploring how AI can enhance spatial audio. It’s not easy, but in some cases, AI is essential. For example, if we imagine a future with personalised auditory reality (AR), the headphones would need to understand the room’s acoustics and adapt accordingly. Imagine being able to block out voices you don’t want to hear — AI would be crucial for that. At the same time, much of this still depends on how the human brain processes sound. We’re also researching ways to recognise and compare acoustic environments.

What do you think is the future of audio technology? Any innovations you are especially excited about?

What we are working on now really excites me. At trade shows and conferences, it’s amazing to see people’s reactions when they hear our demo for the first time. They often can’t believe it’s possible. I’m also curious to see what new ideas the next generation will bring.

What are the current major projects you’re working on?

I’m no longer directly involved in audio coding — that continues at Erlangen. My focus now is on immersive sound. We’re working on three phases. First, we’re supplying recording studios with systems that let them monitor multi-channel mixes without needing 15 loudspeakers. Next, we plan to bring that tech to high-end consumers. There’s a whole community willing to invest in top-quality audio, and we want to serve them. Finally, we’re developing a fully adaptive, personalised auditory AR system. I compare it to wearing glasses; just as glasses enhance vision, these headphones will enhance hearing. You’ll wear them all day, hearing your environment, but with customisable sound — turning down unwanted noise or boosting conversations when needed.

Have you ever collaborated with any Indian musicians?

Yes, we currently have an Indian former student pursuing his master’s who also composes for Indian films. So in a way, yes — there’s collaboration and cross-cultural exchange happening.