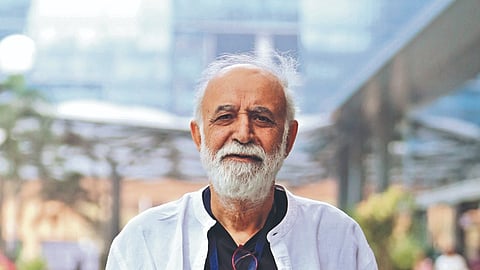

Veteran theatre actor and director MK Raina speaks with a quiet clarity that comes from decades of watching people, places and stories change. Back in Hyderabad, he reflects on why book reading events matter, especially in a time when reading itself feels under threat. He believes these events gently pull people back to books, reminding them of their value in an age dominated by screens.

Raina points out that cities today are filled with coffee shops and food joints, but there are hardly any spaces where young people can simply sit without spending money. “I always feel, where are the youngsters going to sit?” he asks, explaining that libraries can offer that and there are no places for them, unless and until you have good money in your pockets and you can sit somewhere.

A passionate reader himself, Raina says his reading ranges from politics and fiction to cinema and theatre. Speaking about books he feels young people should read, he mentions, “I recently read an author called Volga, who reinterprets Sita, and when it came into English, I could realise its significance even more. It is my political hurt that the Ram Janmabhoomi movement dropped Sita from the discourse. Here, her suffering and sacrifice stand out, as she was born from earth and returned to it alone in protest. Even today, it is always Ram, yet without Sita there is no Ramayana. She represents mother earth and mother India. This simple, beautiful book, where she engages with mythical characters like Shurpanakha, is something youngsters should read.”

When asked about an advice for aspiring actors, Raina does not soften his words. “I would say passion is not enough because knowledge is important, and there is no shortcut in anything. Normally youngsters are driven by glamour or passion, but they do not undergo the rigorous training an actor needs for four to five years, because it is not instant coffee. They believe a short workshop and a few plays are enough, but that mindset will not last, unless their families are very rich and can keep investing,” he expresses firmly.

Raina is equally selective about the scripts he chooses. He says he always asks for the script first and takes his time deciding. Speaking about a recent film set in Kashmir, Batt Koch, he explains why he agreed to be part of it. “The first thing I ask is to send me the script, and if it inspires me with a new idea or new knowledge, it challenges me. Seeing migrant youngsters in Kashmir helped me realise why we are making this film, to support it, and tell the stories of ordinary people that have never been told over the last 35 years,” he says.

His memories of Hyderabad brings a smile, beginning with biryani and moving to folk traditions like Golla Kethamma Oggu Katha and Burrakatha. Yet he worries that traditions are being reduced to symbolic performances. “I feel these traditions need to be reinterpreted because there is a lot of work to be done to make them relevant today. Only then will the tradition survive and the legacy truly live on. I see how the people preserving centuries of Telugu culture are overlooked, and I believe our duty is not to admire it and walk away. When I look around, from architecture to universities where I teach, I hardly see Telugu culture, and it cannot exist only in a handloom shop,” he says.

As the conversation winds down, Raina reflects on his approach to acting. Screen time, he insists, has never mattered. “I see it as a theme because I work with them and sometimes take on very small screen presence roles, but I know exactly why they want me. I can deliver what they need, and this has happened many times. For me, it is the time of the role that matters. No character is small or big, only actors are. I have a certain space, and I must justify myself within it,” he notes.