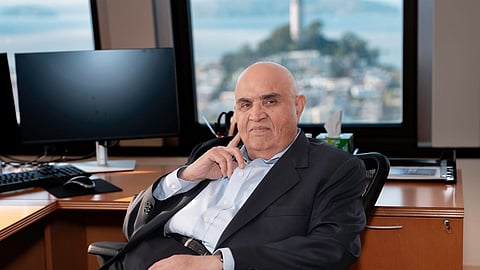

Kanwal Rekhi did not write The Groundbreaker to celebrate success. He wrote it because time, family, and reflection demanded honesty. Now at 80, the pioneering Indo-American entrepreneur looks back on a life defined by being written off, taking risks without permission, and learning leadership the hard way.

Explaining why he chose to tell his story now, he is characteristically direct. “Why now? I’m getting old. At some point, time will run out,” he says. The deeper motivation, however, came from his son, who urged him to move beyond the surface-level understanding people had of his life. “There are a lot of things here that people don’t know,” he recalls his son saying, “There is a very superficial understanding of you. You need to tell your full story, for posterity.”

That impulse coincided with a period of enforced stillness. Kanwal was homebound while his wife was unwell, a circumstance that unexpectedly gave him the time to write. “That also gave me the time to write the story,” he says, noting that the process demanded care and patience.

The memoir is as much about responsibility and failure as it is about achievement — offering an unfiltered look at the forces that shaped one of Silicon Valley’s most influential immigrant founders.

One of the book’s most striking reflections is his belief that being written off especially by his father was ultimately liberating. “I thought about being written off, having low expectations by others, as a liberating experience,” he explains, adding, “People expect you to fail, so if you fail, it’s no big deal. You don’t surprise anybody. But if you succeed, you surprise everybody.” Low expectations, he says, remove pressure and scrutiny: “You’re not being monitored all the time. People just leave you alone.”

He had already made peace with his father long before writing the book, and he is careful not to frame that relationship in absolutes. While acknowledging emotional distance, he also recognises his father as a role model in responsibility. “He assumed responsibility for things around him — for his parents, for his children, for his brothers and sisters,” he notes. Watching him do ‘whatever needed to be done to take care of the extended family’ left a lasting impression.

If any part of the book was difficult to write, it was the chapter on his wife’s suicide attempt in 2003. “That came as a surprise to me,” he expresses, admitting he struggled to understand how it happened within a loving relationship. He adds, “That’s when I became aware of depression and how it plays out.” Unsure whether to include it, he ultimately did so after his wife read and approved the manuscript.

Writing The Groundbreaker did not challenge his beliefs so much as contextualise them. “If I die tomorrow, I will die happy. I achieved much more than I had any right to expect,” he warmly states. He describes the book as an attempt to understand how it all happened. IIT, he explains, taught him first-principles thinking. “It gives you tools — how to take any problem and break it down into its fundamentals,” skills he later applied when learning sales, finance, and leadership as a CEO.

Honesty, he believes, is non-negotiable. He highlights, “One of the messages I deliver to entrepreneurs is: own your failures. Your failures define you, toughen you up, and give you perspective.” He rejects polished narratives: “I am a whole package — good, bad, and ugly. Sweeping things under the rug doesn’t mean much.”

What keeps him engaged even now is curiosity. “Never lose your curiosity. Keep your hunger for knowledge going,” he enunciates. Mentoring young entrepreneurs helps him stay relevant. “When you engage with entrepreneurs, you learn more from them than you teach them. They are closer to technology, markets, and customers,” he states on a concluding note.