KOCHI: In an essay titled Everyday Moments, writer Perumal Murugan begins recounting personal experiences with the line: “caste is like god”. This omnipresent god dangles threateningly in daily life from house-hunting struggles to caste determining if the author must eat a meal on an easily disposable leaf or a family’s steel plate.

“There is no difference in villages, cities, mountains or among the educated or uneducated — god is everywhere; so is caste… everyday moments constantly produce before us visuals of caste” — these thoughts find a place in a 2013 collection titled Black Coffee in a Coconut Shell.

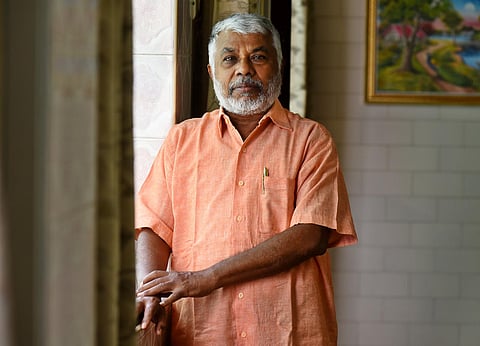

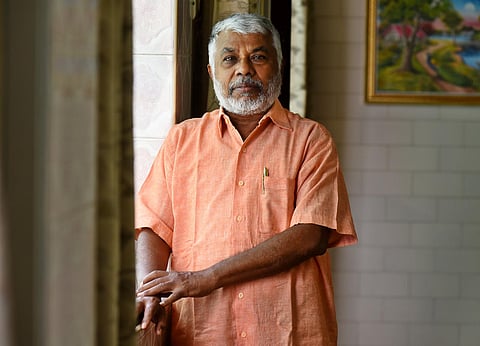

A decade has passed since this collection was published but Perumal’s words continue to ring true. With a long list of prolific works ranging from his novel Pyre (Pookuzhi) to short stories like The Goat Thief, he continues to chronicle tales of discrimination. Earlier this week, for a lifetime of speaking against discrimination, Perumal was awarded the New Indian Express’s Ramnath Goenka Sahithya Samman for Literary Excellence, launched this year.

As the citation notes, “A litterateur of rare empathy and insight, in his oeuvre of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry, he has portrayed the rhythms of rural life with a rare nuance.” After receiving this award, the author talks to TNIE about his new collection of short stories Sandalwood Soap, and the role of love in annihilating caste.

Edited Excerpts:

How do you feel about receiving the Ramnath Goenka Sahithya Samman at the Odisha Literary Festival?

In the name of Ramnath Goenka, this is the first series of awards. There were three categories — fiction, non-fiction, and lifetime achievement awards. They gave me the last one, and I was happy about it. But it also made me feel like I am old!

It’s been over 30 years since your debut novel, Eru Veyyil or Rising Heat. How do you look back on your journey?

It’s been quite good. And these awards seem to cement the same idea. Eru Veyyil has been translated into English, and panels of judges have read this and had meetings and discussions about it. My novel has been translated to other languages, and they seem to have garnered a good impression. That gives me the belief that my path has been good.

The translated collection of your short stories, Sandalwood Soap, was released recently. What was the process and translation like?

Sandalwood Soap is my third collection of short stories,. (Journalist and writer) Kavitha Muralidharan translated it. She had already worked on my interviews, compositions, essays, and book Amma. It is a pleasure to work with her as she has read widely in Tamil and many of my books. In this collection, she translated three of my stories for magazines. It was a natural and jolly process. As my stories feature the Kongu dialect, she clarified the meaning of certain words. I never expected Sandalwood Soap, the titular story, to be selected, as it had been written 20 years ago. I was happy as Kavitha and the Juggernaut editor liked it.

In your essay Everyday Moments, which is part of the collection Black Coffee in a Coconut Shell, you mention that caste is like god. Could you elaborate on that?

Belief in god is inseparable from one’s lifestyle. Caste is like that — one cannot go without thinking about caste, it is everywhere. I wrote that in this context. In some way, even if we leave our villages for cities, there would be something that would make us think or speak of caste, or associate our identity with caste. This is not seen only during weddings when brides and grooms look at caste, but even when we meet someone for the first time physically or on the internet.

If we encounter someone for the first time at a mess in Chennai and he is from Namakkal, the thought of which caste he belongs to runs through our mind. The question of caste enters in a camouflaged way. If they find out they are from the same caste, they want to figure out if they are related. Caste prevails everywhere in that sense in day-to-day life.

Several writers have contributed to this collection. How important is it for writers from different communities to address caste?

I began this collection for that reason, for writers to write openly about caste. While it was not openly spoken about, it did not mean caste did not exist. We can only think about how to (annihilate it) if we all openly speak about caste, think about it.

What role do love and inter-caste marriages play in destroying caste?

Inter-caste marriages play an important role in annihilating caste. Caste is well-protected when many marriages occur within the community and caste. Just like Periyar and Ambedkar have said, as long as marriages within the same caste happen, it will not be eradicated. If one person is Dalit, the couple will have reservation. Reservation must be increased, as only if inter-caste marriages are encouraged will caste come to an end. In cities, such marriages occur, and it is a welcome trend. But in villages and smaller towns, this is not the case. Threats and honour killings still take place. The government must bring in some plan and policy.

What have your experiences been like during teaching? How do you take topics like caste, or gender to classroom spaces?

I would take Tamil literature to class so I would have more of a chance to speak about these topics and for (discussions) to happen naturally. I would converse with my students on caste and gender discrimination through short stories and poems. There would be good responses from students. They accept caste discrimination. However, but (often) male students won’t accept gender discrimination. A lot more discussion and communication is needed for that.

Apart from writing, can teaching also be a form of protest?

We learn gender and caste politics from family and society. It is not easy to remove these ideas recorded in our common sense. It should be a continuous process. Holding flags, slogans and clashes are not the only ways to protest. Protests can be through meaningful discussions. In my experience, I feel writing and classrooms can do this.

What next?

Currently, I am writing short stories. I also plan to write a novel. Over the past four-five years, I have written several essays about freedom of expression. In October, a collection of these essays will be released during the Madurai Book Fair. I have signed agreements for other books to be translated.