The Malayalis of Macondo

KOCHI: Time doesn’t flow linearly in Macondo. It’s circular, fluid - seven generations of the Buendía family live and eventually disappear off the face of the earth. Time alone bears witness to this magical town by the river, founded by patriarch José Arcadio Buendía, who dreamt of a city of mirrors.

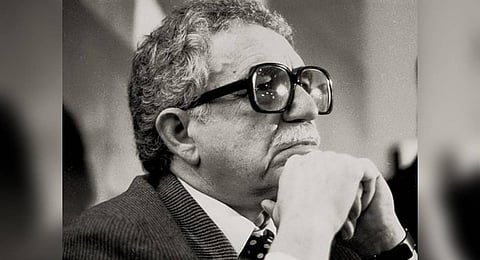

Often regarded as the greatest novel of the 20th century, Gabriel García Márquez’s masterpiece, One Hundred Years of Solitude, transforms Macondo into a sprawling character on its own.

In Macondo, the only visitors from the outside world were gypsies, who travel to the isolated town once a year, drawn by José scientific curiosity. It is they who introduce ice to Macondo.

As José turns insane, his wife Úrsula becomes the matriarch who ties the Buendia family together. The story expands with his son, Colonel Aureliano Buendía, who fathers 17 sons with 17 women, some of them incestuous. And the tale of Macondo unfolds through a multi-generation saga, with layers of Latin American politics over 100 years.

Everything in Macondo is surreal - children are born with tails and butterflies hover overhead like clouds. And reading this magical realist novel becomes a meditative act.

Published in Spanish in 1967, buzz about the novel reached Kerala’s shores in the 1970s through M T Vasudevan Nair’s American travelogues.

The first Malayalam translation of the novel appeared in the 1980s, and since then, Márquez has become a writer loved like no other among Malayalis. A popular joke in Kerala’s literary circle used to be that Marquez was “the best-known Malayali writer in Latin America” and “the first Malayali novelist who won the Nobel”.

Writer S Hareesh recalls those days when the Márquez fever swept Kerala, and ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ achieved cult status.

“I came across Márquez in M Krishnan Nair’s Sahitya Varaphalam,” he says. “His words drew Malayalis to Márquez. I was doing my pre-degree when I first picked up the book. The first try was unsuccessful - I think I wasn’t mature enough then,” Hareesh laughs.

But Macondo had a grip on him, and six months later, he returned to the Malayalam translation by the late S Velayudhan. “The language flows, and the long, winding sentences are never biting. It was a magical experience. The stories within were like a wonderland - I had never read anything like it before,” he says.

For many, Márquez’s novel was an initiation into a new literary style. “I don’t think Malayalam literature would be what it is today without him,” Hareesh says.

According to Hareesh, it was the “familial structures” resembling Kerala, the “emotional aspects” of Latin American literature, and the “superstitions and folktales of the land” embedded in Márquez’s writing that made his work resonate deeply in Kerala. “Moreover, they [Latin America] were also on the path of socio-economic development, like us,” he adds.

Márquez’s hold on the Malayali psyche has been immense. The fantasy became real, the dream universal, the struggles relatable, and the political unrest gnawing.

“A piquing curiosity about one’s neighbourhood, a genetic affinity towards magicalism, and perhaps a sense of alienation because of the failure to assimilate with nature could have been the raw materials that shaped an average Malayali’s reading predilections,” says P Kirathadas, a former English trainer and author of the book ‘Smruthiyorangal’.

He believes young Malayali readers had found an “escape” from the politically and socially committed fiction of their time and the “zig-zagging, poetic feudal stories” of earlier literature with the arrival of O V Vijayan’s Khasakkinte Ithihasam. “Márquez was received with the same enthusiasm. Add to that his innate spirit of rebellion and his friendship with [Fidel] Castro, who was viewed as an icon here,” he says.

“Márquez’s writing was an absolutely original style - sweetly distressing magical realism with occasional escapades into realms of fantasy and the hazy world of ghosts.”

These qualities, Kirathadas says, allowed Malayalis to “get lost in nostalgia for an abstract, non-existent past.”

“I read One Hundred Years of Solitude for the first time during a long train journey in the ’80s. The magicality of the narration transported me from the lakes and green paddy fields passing by to the landscape of Macondo,” he recalls.

“The periodic appearance of nomadic gypsies made Macondo colourful. Like from an enchanter’s magic box, they brought out curios—each one with many stories to tell... It was the intriguing circles in the writing style that made me love the book. I still remember the wonderful lines: Every year during the month of March a family of ragged gypsies would set up their tents near the village, and with a great uproar of pipes and kettledrums they would display new inventions.’ Then the wonders followed, one after another!"

Never before was there a foreign writer Malayalis loved as much as Márquez. They hung on to his every word, and Macondo became a village by the river they all felt they had visited. The many wars, lores, fantasies, magic, and inventions — all unfolded before their eyes. Never had someone conjured a story so unrealistic yet relatable.

It was these elements that captivated Aleena, a writer who discovered the book when Márquez was already a literary giant. “He was a god-like figure to us,” says the 28-year-old.

When she picked up the English translation, she was struck by the simple charm of his prose, right from the opening line: Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.

“Can you believe — ice? And it’s the simplicity of it, a mundane object like ice, that drew me in,” she chuckles. Aleena notes that many Malayali writers emulated Márquez’s style. “He said what he wanted without much decoration — simple and straight. And many of our writers follow his style now. It’s here that I learned to completely give myself up to a story. The suspension of disbelief is complete when you read One Hundred Years of Solitude,” she says. And even now it remains, a favourite among her list of favourite books.

For photographer and communication designer Ranjith Chettur, it’s the power of imagery in One Hundred Years of Solitude that swayed him. “The landscapes in Macondo are easy to imagine. You don’t have to be there or even know where Latin America is — you can vividly see every image, including the gypsies, like the circus of my childhood,” he says. “I have read the book at least four times. For me, One Hundred Years is a collection of vivid imagery.”

Writer K R Meera shares similar sentiments. “When I first read the book, at 18, Márquez had already won the Nobel Prize (1982). Writing like him, creating such powerful images in every reader — who wouldn’t admire that?” she smiles. And young Meera became that avid fan, who wanted to be like the man who wrote her most-cherished books.

“The concept of a city made of mirrors was so intriguing that I started imagining a Kollam made of mirrors! Remedios the Beauty, surrounded by yellow butterflies, levitating to the skies; Rebecca eating dirt in her sorrow; Colonel Aureliano Buendía facing the firing squad… These are not words – they are powerful, indelible images.”

Meera says she later understood the metaphors behind the fantastical events in Macondo. “With the history of Colombia unfolding through books and the internet, you can read ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ with a completely new lens. Now, we can understand so much more.”

As Macondo reaches screens on November 11 through Netflix, readers are curious: will the city of mirrors match their imaginations?

Gabo love

With over 50 million copies sold worldwide since 1967, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ has remained one of the most influential books ever in world literature. The book, which became a sensation in Kerala, was officially translated into Malayalam before it won the Nobel Prize. Interestingly, Malayalam was the second language into which the book was translated, after English. “Even now, Marquez’s books are as sought-after. It’s the nature of his writing, especially the magical realism, that captivates Malayali readers. Just like Khasakkinte Ithihasam by O V Vijayan, One Hundred Years of Solitude has been a path-changer in Malayalam literature,” says Ramdas Rajan, deputy editor of DC Books.

Some other fan faves by Marquez:

Chronicle of a Death Foretold

Love in the Time of Cholera

Strange Pilgrims

The Autumn of the Patriarch

Memories of My Melancholy Whores