KOCHI: The oldest form of prayer likely centres around the worship of the feminine. Across regions — be it Indian, European, Arabian, or African — every civilisation included prayers to the divine feminine as part of their worship culture.

The Shakta cult remains one of the hallmarks of India’s spiritual heritage. Here, Shakti, or energy, is personified as a female entity, and this energy is the force that creates, sustains, destroys, and enables life.

This Shakti is revered most during the nine nights of the year when the country unites to celebrate nine exemplary forms of feminine power.

Navaratri has unique regional characteristics across India. In the north, the goddess is worshipped as a caregiver and protector, with devotees observing fasts and holding night-long prayers for her blessings.

In the east, the goddess takes the form of the valorous Durga, whose fiery image, often shown defeating the demon Mahishasura, is crafted from clay and worshipped for nine days. In the west, Navaratri rituals invoke Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and abundance.

In southern India, the goddess is celebrated in different ways during the nine days. In Tamil Nadu, the first three days are dedicated to Lakshmi, the next three to Durga, and the final three to Saraswati.

Nature, or ‘Prakriti’, is also worshipped through the ‘golu’ arrangement, where dolls depicting themes of mythology, environment, and life are displayed on makeshift staircases. Some of these dolls are passed down through generations. The ninth day is dedicated to ‘Ayudha Puja’, where tools of work and weapons are worshipped.

Karnataka has similar celebrations, with homes displaying dolls and temples in full grandeur. Art festivals are organised at many places, including the famous Mookambika Devi temple at Kollur, known as a seat of learning.

The Mysore Dasara spectacle coincides with the Navaratri festival. Mysore is named after Mahishasura, and legend says that the region, then called Mahisuru, was ruled by him before the goddess Chamundeshwari of the Chamundi Hills defeated him.

In Andhra Pradesh, the nine days are dedicated to Maha Gauri, representing womanhood. A unique regional ritual is ‘Bathukamma Padunga’, where women make flower stacks for nine days, which are floated on water on the final day.

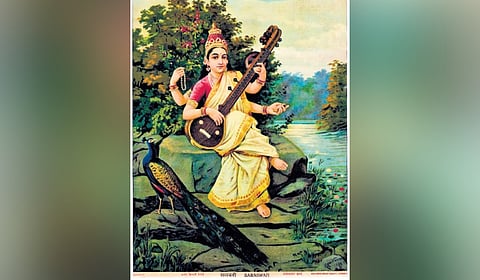

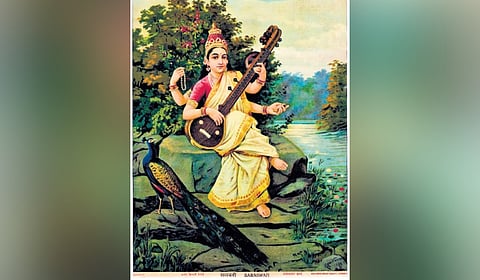

Kerala’s Navaratri customs are distinct, with the entire period predominantly dedicated to Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge. Recent years have seen the introduction of chants of sacred texts during the festival, but the predominant practice is the prayer to the deity of letters.

On the eighth day, the ‘Poojaveyppu’ ritual is observed, during which people place their work tools and study materials before the goddess, along with flowers, fruits, and agricultural produce. These offerings are worshipped for three days, from the eighth day (Ashtami) until ‘Vijayadashami. After prayers, the books, instruments, and tools are taken up again, symbolising a renewed commitment to the blessings of the goddess.

Toddlers start their educational life with a ritual called ‘Vidyarambham’, where an illustrious adult or priest writes the first letters of the alphabet on the child’s tongue. Grown-ups, meanwhile, write the letters on sand or raw rice. Artists begin their art life afresh or with renewed vigour by offering their obeisances to their gurus.

These rituals have roots in Kerala’s Tantric tradition. “The Kerala school of Tantra is one of the three main branches of Tantra in India, the others being the Kashmir and Gaudiya schools,” Ashwin Salija Shrikumar, a researcher in plant biology and expert in Tantric studies.

“The Kashmir school was practised more in the north, and the Gaudiya in Bengal. In Kerala, the goddess worshipped during this period was predominantly Lipi Saraswati, the goddess of letters. She embodies the energy behind sound and language. Lipi Saraswati, or Vaagdevi, is invoked for proficiency in learning, to enable deeper study of any subject.” The worship of Lipi Saraswati as a form of the divine feminine in Kerala coexisted with other forms of Shakta worship. The relatively peaceful environment of the region fostered learning and intellectual growth.

“Sharadiya Navaratri, observed in October-November (as per traditions, there are four Navaratris in a year, the popular one being the Sharadiya), is also associated with Lord Rama, who sought blessings from Jaya Durga, or Mahakali, to prepare for his war against Ravana. This is why the fiercer forms of the goddess are worshipped in most parts of the north,” Ashwin says.

Although ‘Poojaveyppu’ and ‘Vidyarambham’ are observed across Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram’s celebration has a unique historical significance. It dates to the 13th century, when Tamil poet Kambar, famed for his rendition of the Ramayana, entrusted an image of the goddess Vagdevi, or Saraswati, to the Chera king, anticipating his death.

He asked the king to ensure that the goddess was worshipped exclusively during Navaratri. The Chera kingdom, later transformed into Venad and then Travancore, followed this tradition. When the capital moved to Thiruvananthapuram, the custom of bringing the idol to the city for Navaratri began.

“The goddess is kept at the Navaratri Mandapam near Sri Padmanabhaswamy temple and worshipped with offerings of music and dance. Swathi Thirunal (1813–1846), the legendary composer, even wrote nine songs for the nine evenings of Navaratri. The promise to honour the goddess is still being kept,” says Aswathi Thirunal Rama Varma, musician and member of the Navaratri Mandapam Trust.

Thiruvananthapuram maintains Navaratri’s traditional fervour, while border regions like Palakkad and Malabar reflect the customs of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka.

“However, across Kerala, ‘Poojaveyppu’ has become a norm. In Malabar, the Theyyam and Thira performances begin after Navaratri, so the festival has significance in those regions too,” Ashwin notes.

Historian Vellanad Ramachandran points out that the festival was historically celebrated with equal enthusiasm in Kochi and central Kerala, likely due to Pandya influence.

He also suggests that Navaratri has caste connotations, with writing considered inferior to the oral study of scriptures. “This may explain why castes like ‘Kaniyars’, who prepare astrological charts, and artisans, who carved temple inscriptions, were initiated into the world of letters,” he explains.

Writing, at the time, was seen more as a skill than a mode of acquiring knowledge, which was typically passed down orally among the learned.

The caste debate is rooted in interpretations of who qualifies as ‘learned’, according to Ashwin. “Ideally, the learned are those who make the pursuit of knowledge a habit,” he says.

“However, this has been misinterpreted, creating wedges between the learned and the less learned. This later led to social divisions. Can we blame knowledge for this? It has more to do with power and the human mind.”

Despite its complex history and philosophy, Navaratri in Kerala today is a festival that unites different cultures. The state, a melting pot of diverse cultures and traditions, celebrates with equal enthusiasm ‘Dandiya’ from Gujarat, Bharatanatyam performances, Carnatic concerts, and Bengali cultural extravaganza.

It is a celebration of prayer, learning, art, and joy, as the divine feminine is honoured.