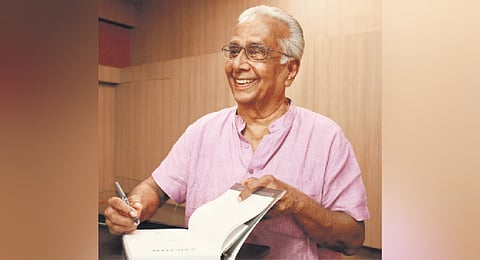

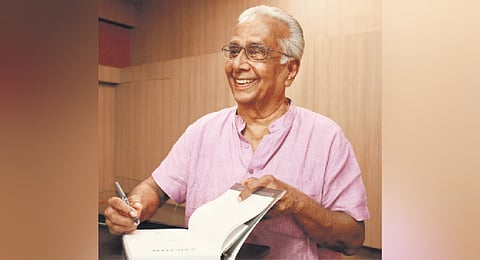

Were you always interested in history?

Oh, very much! In school, we had a subject on just Cochin history in addition to, of course, India and world histories. I was very fascinated, especially by the old Roman and Egyptian empires. Though I pursued economics and politics later, I always harboured a love for history. It is inescapable and weaves its fingers in all fields, especially politics.

What was the impetus for beginning work on the book?

It was the coffee table book that I was working on for the Cochin Port Trust which covered the socio-cultural life of Kochi and its people. Because the scope of the project was different, political history was only cursorily covered. This got me thinking — why not a book that was broader in sweep and scope: about the transformation of a cluster of fishing villages, which is what Kochi was to begin with, into the metropolis that it is today?

The spark was thus lit, but it wasn’t until I had completed another book, The Saga of Kalpathy, that I gave the idea any further thought. My friend and local historian V N Venugopal prodded me to write a story on a place now that I had completed one on people (on Tamil Brahmin community in Kerala in Kalpathy). Thus began the work, albeit slowly…

Why do you think there were no comprehensive history books on Kochi before this?

See, there’s no dearth of documents. The difficulty is only in accessing the materials. Getting into the archives, filing for permissions, etc. Even then, the state resources are in complete disarray. Several documents are in tatters and efforts to preserve them have not yielded the desired results.

That said, there are untapped resources as well. While working on my first book on the Cochin Chamber of Commerce turning 150, I was given access to the Chamber’s archives. It was a treasure trove of information on how the city grew, with documents stretching as far back as the 1850s. Surprisingly, no one had bothered to make use of them.

Did your research primarily revolve around archival material?

Yes and no. While archival material made up the bulk of my research, I also had long conversations with people who were in the know, with friends who were experts and even accessed a few personal documents. However, oral history has limitations. Subjectivity can seep in. They must be supported by documents. Hence, my greater reliance on archives.

One can also get bogged down in research…

Yes, no doubt! That’s where my experience as a journalist came to the rescue. I could establish connections relatively easily. I was a journalist at a time when ‘looking up’ something on the Internet wasn’t a thing. We were trained to look for connections between seemingly siloed events, learn about their backgrounds and sift through materials to make sense of the larger picture. Nevertheless, it took me over three years just to collect all the details and about a year to write it. But it was a labour of love.

Do you miss journalism?

Very much. The best days of my life were when I did reporting work. Meeting people, going to places. Getting a byline was a big spur at the time. Also, there’s nothing like pursuing a story on your legs. You come back not with one story, but three. The personal connections you build and the leads you develop are also very rewarding.

Is this your advice to young journalists?

Yes, I will also add. Talk less, listen more. Never say no to people who come to talk to you. Try to read widely. Ask everything about something and something about everything. Learn to find the connections. Also, don’t rely on the internet too much.

I’m told there’s a sequel in the works…

Not yet, but I think there is a need — to cover the arts and cultural aspects of the city. We dropped it from this narrative as I feared that it would take away the focus. The book would be spread too thin, fragmented even. So I’m very interested in seeing a sequel done.

In your work, the Cochin Chamber of Commerce, we learn, was an institution of much influence. Has this waned?

I’m afraid so. It’s high time they stepped up and worked out a long-term plan for the city. They could start by preparing a master plan for Willingdon Island, where their office sits. The nearly 750 acres of land here could be better used to prop up the IT industry or assemble a factory district. Like how British engineer Sir Robert Bristow envisioned.