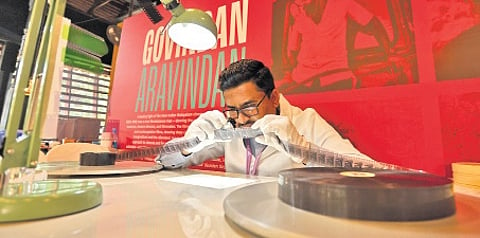

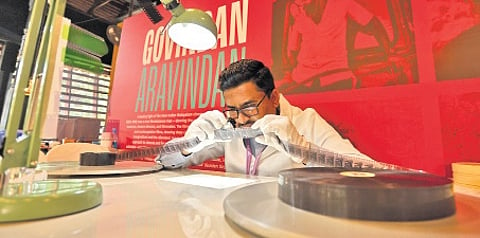

THIRUVANANTHAPURAM: Malayalam film veteran G Aravindan once famously remarked that he may not believe in God, but he did feel the mystical was as real as reality itself. Among his works, the film that most deeply bears this mysticism is ‘Thampu’, made in 1977.

Shot in black-and-white by another veteran, Shaji N Karun, the film captures, with poignant silence, how a village by the banks of the Bharathapuzha responds to a roving circus troupe setting up base there.

It reflects the rawness of villagers who had never before seen a film unit or a circus company, the transience of human relationships, an empathetic perspective on the rich-poor divide, and ultimately a search for deeper purpose.

Aravindan’s freewheeling filmmaking won the film cult status and a sacred place for him in Malayalam cinema. It also wove together many marvels — Shaji’s visual poetry, the serene presence of Sopanam legend Njeralath Ramapoduwal, the acting prowess of Bharath Gopi, and the early spark of Nedumudi Venu, who went on to become a legend.

“It was appalling to find that the original camera negative of this film (like other Aravindan works) had not survived, and whatever remained was in a pathetic condition,” says ace film archivist Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, who is in Thiruvananthapuram as part of the ninth edition of Film Preservation and Restoration Workshop India (FPWRI).

“After a wide and futile search for good film elements from which it could be restored, we found that we could use a dupe negative struck from a 35mm print that was at the National Film Archives of India (NFAI).”

Thus began a two-year journey led by Shivendra’s Film Heritage Foundation (FHF) to restore this classic – a joint project with Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation and Prasad Corporation Pvt Ltd.

The scanning and digital clean-up were conducted at the Prasad Corporation’s Chennai facility under the watchful eyes of Davide Pozzi, director of L’Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna, one of the world’s top restoration labs.

The team consulted the auteur’s son, Ramu Aravindan, as well as Shaji and producer K Ravindranathan Nair. After renaming the film ‘Thamp’ (instead of ‘Thampu’, as it was previously spelt), the restored classic premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2022.

“A similar process ensued for ‘Kummatty’, another Aravindan classic,” says Shivendra.

“In the past 10 years of FHF’s existence, we have been able to restore several landmark films, including ‘Ghatashraddha’ (1977), the first from Girish Kasaravalli’s stock, and ‘Manthan’ (1976), a film by Shyam Benegal on India’s White Revolution.”

‘Just one print of Amma Ariyan’

Another Malayalam masterpiece undergoing restoration is John Abraham’s ‘Amma Ariyan’. “Can you imagine that there is just one print of that film in the entire world? And if that gets damaged, the film will be lost forever,” rues Shivendra.

This, according to FHF, is the grim reality for 95 per cent of films made before 1995. For instance, the original negative of Shaji’s award-winning ‘Piravi’ (1991), based on the story of Prof. T V Eachara Warrier, whose son Rajan was killed in police custody during the Emergency, does not exist in India.

A few prints remain in the Fukuoka Archives, Japan, and in a Switzerland archive, but they are heavily subtitled in local languages, making it challenging to create duplicate negatives.

“The need for preservation is urgent,” says popular film critic C S Venkiteswaran. “Earlier, all technical work was done in Chennai labs, and the negatives and prints were typically stored there. Producers were responsible for safeguarding the prints, but after the film’s run, they would often be discarded without thought of future relevance. Distributors would sell them as scrap, and in some cases, silver would be extracted from the nitrate in the prints to make ornaments. However, there is a Central directive to preserve some films that have won national awards.”

Since 2015, FHF has been organising FPWRI, a “travelling school” that has trained about 400 participants nationwide. This year is special to Shivendra, as it is being held in the hometown of his mentor and a pioneer in Indian film archiving P K Nair.

Notably, the project in Kerala has the backing of several legends from the world of cinema.

“Some of the most remarkable pictures I have watched have come out of Kerala, whose cinematic heritage includes the work of Adoor Gopalakrishnan and Aravindan Govindan,” says eminent filmmaker Martin Scorsese, who heads Film Foundation, a global non-profit dedicated to film preservation.

“The World Cinema Project, an arm of The Film Foundation devoted to the restoration, preservation and dissemination of films from around the world, recently restored two of Govindan’s films, ‘Kummatty’ and ‘Thamp’, in partnership with Film Heritage Foundation.”

Bollywood actor Amitabh Bachchan, the cause ambassador of FHF, hopes the workshop would “sow the seeds of a film preservation movement in Kerala, which despite its incredibly rich and artistic cinematic legacy, does not have an archive”.

“As Malayalam cinema continues to make waves around the world, I hope that the film fraternity, cinephiles and the government will remember that film preservation is about the future – saving yesterday and today’s films for tomorrow – and that this workshop holds the key to that door to the future,” he adds.

Actor Kamal Haasan, who is an adviser to FHF, stresses that there is an “urgent need to preserve our film heritage”. “The world has lost a vast amount of our film heritage and we need an army of archivists to preserve our cinematic legacy and also work to save the films of today and tomorrow,” he says.

The workshop features resource persons from renowned institutes like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the British Film Institute, L’Immagine Ritrovata, Institut National de l’Audiovisuel, Fondation Jerome Seydoux-Pathe, and Cineteca Portuguesa.

Topics covered include film heritage programming, film repair, cataloguing, video and audio tape digitisation, digital technology, scanning, remastering soundtracks, and preserving paper and photographs, led by global experts. Notably, the participants will be certified by the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF).

“The workshop is being attended by over 66 delegates from across India and countries like South Africa, Brazil, Sri Lanka, South Korea, and Australia. Yet, the response from younger filmmakers of Kerala and the state government is not encouraging,” says Shivendra.

He adds that the state’s film sector did not even have a rotating table to mount the reels on for restoration. “We had to fetch two from Mumbai, and we will be donating them here. This shows the poor state of the state’s film heritage. We are training 30 people from Kerala, hoping they will spur a change,” says Shivendra.

“Kerala is a state that has a deep love for cinema and two major film institutions, the Kerala State Chalachitra Academy and the Kerala State Film Development Corporation, but sadly it does not have a film archive to preserve its incredible film heritage. The situation is dire. We found that so many films were lost and many others deteriorating due to neglect and lack of knowledge about preservation.”

‘Raja Harischandra is still in good condition’

Film preservation in the analogue is challenging due to space constraints and the laborious and costly process of preserving copies and negatives. “Vaults with adequate power to maintain a temperature of -13°C are needed to ensure about 100 years of storage. Without this, analogue content erodes quickly,” says Shaji.

The veteran filmmaker urges cinema lovers to get proactive. “Films are now considered heritage, but there is still little awareness about preservation,” says Shaji.

“Three years ago, we sought a regional archive in Munnar, but no action has been taken. For celluloid films, three years is precious time. Government funds are available — Rs 650 crore has been set aside for heritage preservation. What we need is a concrete plan of action. More archives, vaults are essential.”

While digitisation seems a quick solution, and young filmmakers may feel secure with digital storage options, Praveen Singh Sisodia, an FHF faculty member in film repair, argues that the good-old acetate film can last long. “We just need to ensure proper cold storage. India’s first film, ‘Raja Harischandra’, is still in good condition,” he highlights.

Echoing similar views, renowned filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan says: “It is proven that the optical film has survived for more than a century and beyond under controlled humidity and heat. The digital film’s longevity is a matter of faith and belief yet to be verified by real experience over a length of time. Those who wish a longer life for their films should have them transferred to celluloid scientifically, using modern methods of preservation. The workshop will equip and empower the motivated.”

Shivendra believes filmmakers should parallelly think about preservation.

“It is an art that requires technical know-how but, more importantly, a creative mindset. We are in awe of filmmakers like Adoor Gopalakrishnan, who have taken steps to ensure their work is well cared for,” he says.

“Kerala’s rich film heritage is in danger of vanishing if we don’t take urgent steps to preserve it. The state should have a proper archive. We hope that through the training and exposure to the best practices of film preservation at the workshop, we will be able to set this process in motion.”