The dictatorial and brutal Khmer Rouge regime under the tyrant Pol Pot in the mid-to-late 70s in Cambodia and the genocide engineered by it of over 2 million civilians have been perennial preoccupations in the works of Rithy Panh. The Cambodian documentary filmmaker-writer-editor’s own family faced expulsion from the nation’s capital Phnom Penh, and his close relatives, including parents and sisters, died of starvation even as he managed to escape to Thailand.

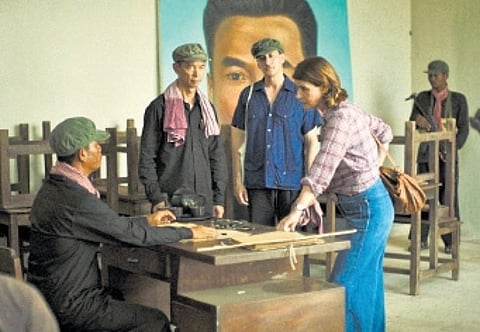

With his latest film, Meeting With Pol Pot, he enters the same zone—Cambodia—again, albeit as a fiction filmmaker. Based on the book by Elizabeth Becker, his latest film is about three French journalists—played by Irene Jacob, Gregoire Collin and Cyril Guei—invited to Cambodia by the Khmer Rouge in 1978 to conduct an exclusive interview with Pol Pot.

Though Panh uses his familiar narrative patterns—mixing archival footage, newsreel and clay figurine scenes with dramatic acts and performances—the film is as much about the inhuman phase of Cambodian history as it is about the role of journalists reporting on it. An ode to Panh’s own The Missing Picture and Roland Joffe’s 1984 classic The Killing Fields.

Panh brings the ethics of journalism into focus through three pairs of foreign eyes and perspectives—one political, other apolitical and a third compromised and in cahoots with the despots. It raises several questions which, while being rooted in history, have a contemporary, universal ring—does a set-up, conducted tour/junket kind of interview opportunity even qualify as a genuine inquiry and coverage? How do you get past it and search for the horrors of the truth hidden behind the ruse of “all is well” propaganda? How loyal should you be to someone who has offered you a story? All of it resonates in terms of what media has been reduced to across the world. It’s about how a pliable media can get insinuated in building a convenient narrative by manipulative governments. It’s both a morality play, and a cautionary tale.

In an exclusive interview with TNIE at the film’s world premiere at Cannes Film Festival, Panh talked about switching between fiction and documentary filmmaking, the role of cinema in capturing contemporary complexities in the light of history, the use of archival footage and clay figures in his filmmaking, about a filmmaker’s own engagement with the subject of his work, the involvement and distancing required and addressing issues of extreme violence in cinema.

Excerpts:

Meeting with Pol Pot is fiction filmmaking. How is it for you to alternate between fiction cinema and documentaries and weaving fact with fiction?

I have always liked making films but what I like the most is this kind of freedom I have learned from the older filmmakers like Dziga Vertov and Chris Marker. It is very important for me to have freedom to create my own thing within the art and craft of the classic form. Sometimes fiction cannot be filmed well. Whatever you do feels less strong than what you envision for the film. So, I try new forms to express, I experiment. The cinematic possibilities then feel exciting to me. And I think it works well in the film eventually.

Did you think of the present film as a documentary first or as a fiction film?

I never start by considering whether I will make a documentary or a fiction. It’s not to do with the standard definitions. When I make a film, I just make a film. I don’t talk too much about its category or form.

If you fictionalise reality, you can’t tell a story in the documentary form. But even in a documentary by framing reality in a certain way, with the cuts and editing, you make it a subjective interpretation anyhow.

What is about Elizabeth Becker’s work, on which your film is based, that you find fascinating?

It was a very important work then and is still important now. How many journalists have been killed in Gaza, in Africa? What is the role of journalists and what are the ethics of journalism in conflict situations? Is it to show what is visible or make people aware of that which is not visible? What is the correlation of journalism with ideology? All these subjects interest me. They are in Chapter 11 of the book and echo today’s situation.

There is a great change with the entry of Twitter and Instagram on mainstream news and information channels. There is this necessity for us to immediately take sides. But as human beings we need to step back sometimes. We need to take 30 minutes, maybe one day to form an opinion. Unfortunately, you wake up in the morning and switch on your TV or go to your social network to see the wars and conflicts, people screaming and shouting in discussions. It may seem like freedom of expression but it’s not. There is no maturity. You just want to exist by yourself, you start to talk to the world early in the morning and you don’t even know who you are talking to or what the source of your message is.

How to write an article, how to report about a situation, how to investigate. It looks like we have access to information but it’s too much information coming too fast with no time to think and react. We are working like machines. Before we react to one subject, another takes over. People are not reacting any more. They believe everything, not just the facts but they do nothing.

Pure ideology, radicalisation, woke culture. I am scared about that too. I wonder how people can live together if they have to take sides? You are with them or with us. You are an enemy if you are not with me.

How did Elizabeth Becker react to the film?

She was at the premiere and for 10 minutes I was scared. After all, it’s her story. But she allowed me the liberty to do it my way, using my narrative form and devices. It was liberating and a good sign that she accepted it so well. She is generous.

You have been consistently looking at the history of your nation but there’s so much in your new film which is contemporary and universal. Is it the way you have thought through the film? Or is it for viewers to pick those meanings?

Both. In fact, I’m happy when you can take the film and make it your own. It’s the most beautiful gift for me as a creator. I have experienced life and sometimes what I see today reminds me of an echo in my past, like radicalism, pure ideology, and information overload. I just try to bring it back in my films. When the Khmer Rouge started killing people they talked very little. Now we either don’t talk or talk too fast. We don’t discuss, we don’t hold dialogue. History has a way of repeating itself. And we don’t do anything to stop that repetition from happening again.

Doesn’t the idea of revolution, to bring in a change also come with its own contradictions? The movements often lapse into violence.

Revolution happens when there is no justice. You take to revolution for more freedom, to live correctly and with dignity. But the leaders often end up using people. They bring hope but also often deny it eventually.

The usage of archival footage and the device of clay figures—why did you integrate them in the fictional narrative?

It helped create just the right distance from the subject. The extreme violence, rapes and brutality in the situation is very hard to miss. So how to have the crucial correct distance that it plays right on screen? Even after so many years in filmmaking I am not capable of portraying violence as yet. I don’t think I can show an actor killing another. These devices like the figurines help project the real violence without me having to recreate it on screen.