In an ideal world, every compelling film would be followed by a conversation with its creator—a chance to unlock its mysteries, absorb its truths, and confirm our conclusions. That’s the magic of festivals: they make this ideal a reality.

On day 7 of the 55th International Film Festival of India, Goa, director Mariana Wainstein graced the screening of her film, Linda, offering a brief but potent preface. She took to the microphone and, with disarming honesty, warned the audience that her film might be “uncomfortable.”

The discomfort begins immediately—dog poop, an ant drowning in a drink. These small, visceral moments set the tone, preparing us for a film unafraid of unease.

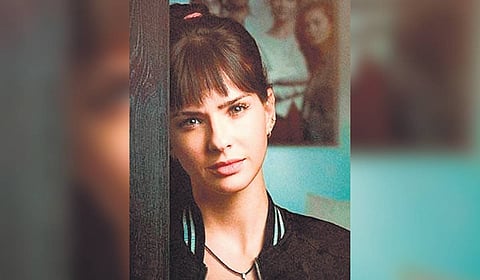

The premise is deceptively simple: a beautiful woman, Linda, who might have been a successful model in different circumstances, joins an Argentinian upmarket household as a maid. Her arrival is like a spark in dry grass—subtle at first, but inevitably incendiary. The family’s discomfort is palpable.

If Linda were plain or unremarkable, she might have slipped into the background, easily invisible. But her beauty refuses to be ignored, becoming an undeniable presence that disrupts the household, creating waves of tension—sexual and otherwise.

The film often takes Linda’s side, showing how quickly she becomes sexualised by the men and women around her, and likely even by us, the viewers. Yet, this sexualisation is not entirely ours to own; it is partly shaped by the film’s gaze itself—a layered, almost meta-commentary on how society collectively consumes beauty.

While I found the indulgent shot of her cleavage unnecessary, teetering close to the very obsession it critiques, the film largely succeeds in making us question the inherent voyeurism in how everyone views Linda.

What made Linda fascinating for me is its refusal to vilify the family members outright. Another film—a more judgmental one—might have portrayed them as caricatures of privilege, entirely irredeemable. Instead, Wainstein extends a surprisingly empathetic gaze to everyone, capturing their flaws without dismissing their humanity.

The husband flirts with Linda in predictable ways—playing music, showering her with gifts, and offering to drive her places—but he stops short of coercion. The children, a son and a daughter, stumble through their burgeoning sexual awareness, their curiosity tinged with some innocence.

The wife, on the other hand, is a more complex figure. In an unexpected twist, Linda reciprocates her attention. Their relationship transcends class differences, rooted instead in shared loneliness and unspoken parallels of a life defined by duty.

In this way, Linda resists the simplistic dichotomy of victim and oppressor. It neither glorifies Linda as an angelic figure nor demonises her employers. Her agency, though constrained by the rigid hierarchy of her environment, is still present and layered. This nuanced portrayal stands in stark contrast to Indian films like Nenjam Marappathillai, which reduce maids and their employers to certain stereotypes in pursuit of exaggerated drama.

After the screening, Mariana Wainstein engaged the audience in a lively discussion. When I asked whether she saw the sexual relationship between the wife and the maid as inherently problematic, her response, like the film’s, leaned towards humanising the characters.

“I don’t want to make that judgment because the wife has her vulnerabilities too,” she said. “Linda, meanwhile, doesn’t mind channeling her needs and desires, in much the same way any of us would in a moment of passion. It’s also a family living under the illusion of harmony.

Linda disrupts that, but soon enough, they brush it under the carpet—just as families often do when faced with uncomfortable truths that threaten their comfortable delusions.”

For all its exploration of physical desire, Linda is ultimately about disconnection. The family, cloistered by privilege, has become estranged from its own emotions. Meanwhile, Linda—oppressed by both class and work—is somehow freer, more in tune with her desires.

Her liberation, though imperfect and shaped by her constraints, feels poetic, almost just. In Linda, Wainstein invites us to confront not just the messy intersections of class, beauty, and power but also the ways in which desire—and its suppression—shapes our humanity. It is a film that lingers, not just for the discomfort that its filmmaker warned us of, but for the complex, relatable truths it dares to reveal.