Who was Bhagat Singh? Was he the ardent patriot as shown in Bollywood movies? Or a lover boy (considering he sang Heer while in prison)?

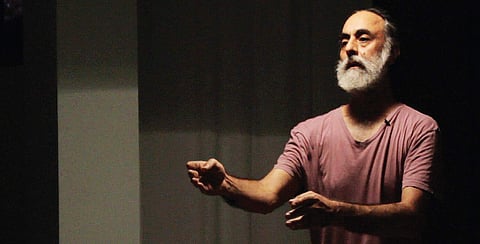

Dancer Navtej Johar tries to get you the answers to these questions as he explores the extremes of Bhagat Singh’s character in his solo show Tanashah at The Stein Auditorium, Habitat World, India Habitat Centre.

Tanashah is based on the jail diaries of the much-revered man in India, including his essay Why I am an Atheist. The show examines the resolve of a young man to walk to the gallows with searing clarity, totally unaffected by the religious doctrine or idealist philosophy.

So how did Johar choose Bhagat Singh? And why Bhagat Singh?

“The piece was commissioned by the Serendipity Arts Festival. Initially, I was told that one of the themes that the festival was considering was the charpai, so if I could possibly make a piece keeping that in mind,” says Johar.

Though Johar wasn’t too excited by the idea, it kept floating in his head till one day he suddenly saw the image of Bhagat Singh in his mind’s eye, sitting on a charpai, shackled, inside Lahore prison. He then began reading about the much-loved freedom fighter — took notes and made a collage of images and ideas. He then began working on the text, which, to him, was the toughest part. “To decide what to keep, what to leave, and how to sequence things isn’t easy,” he says. For the music and songs, he decided to mix portions of Waris Shah’s Heer, padams from his Bharatanatym repertoire, and ghazals from Ghalib. “I also had to find ways to interweave Bhagat with Navtej. All along, I kept improvising with this growing material, trying and testing different ways to string everything together,” he says.

The many articles written by Bhagat Singh left a deep impact on him. “I could identify with him, especially the way he questioned society, religion, and the idea of God,” he says. Quite expected since just like Bhagat Singh, Johar too detests religion though the idea of spiritual-atheism fascinates him — he calls religion inherently violent and a means of control while the idea of spiritual-atheism is inherently open-hearted, and poetic.

So why call an act on such a person Tanashah? He is quick to reply, “because Bhagat Singh is heckled by that name by his friends who feel that he is strong-willed, doesn’t take no for an answer easily, is persistent in pushing his argument & getting the last word.”

How much work did bringing forth those pathos, pain, calmness and clarity in his performance entail, all of which Bhagat Singh must have experienced back then? “Frankly, I don’t see much pain or pathos in his life, at least, he does not let it be known. He remains bold and challenging even in the face of death,” says Johar.

“Portraying Bhagat Singh was not very difficult,” he says, “he is a very inspiring character, he had searing clarity at a tender age of 23, and I find his courage almost infectious.”

Johar sees Bhagat singh as a passionate, bold, clear-sighted, sure-footed, deeply enquiring, and most of all a rasik. He sings Heer while in prison, is an avid reader, and delights in the poetry of Ghalib, Tagore, Iqbal and Wordsworth among others.

And the fact that he could actually relate to Bhagat Singh’s journey further made Tanashah easier.