Loss is a theme in many great melodies, whether it be Radha longing for Krishna in the Bhajana Paddhati or Rodolfo mourning Mimi in Giacomo Puccini’s La boheme. But there is no playlist for grief. As the famous Hindustani classical musician Pt Sajan Mishra mourns the passing of his elder brother Rajan, he recalls their first performance at a haazri at Varanasi’s famous Sankat Mochan temple in 1967. Rajan was 10 years old, Sajan five. Since then, the brothers sang together for the next five decades.

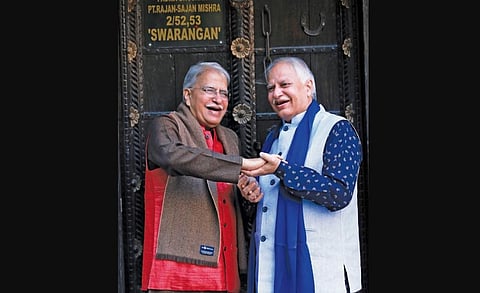

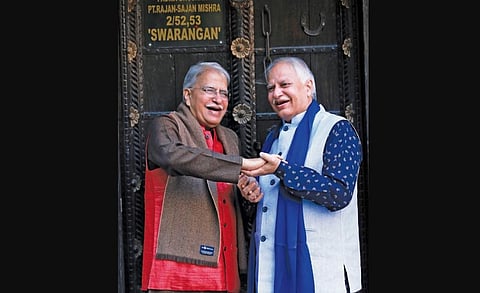

“We performed across the world. Ours was a relationship of friendship and respect. It is very hard to sum it up in words,” says Pt Sajan Misra about his elder sibling. It is always Rajan who occupies centrestage in his brother’s mind. Rajan the intellectual. Rajan the composer. Rajan the interpreter of nuances. The Misra brothers were born in a musical family in Varanasi, the UNESCO City of Music. Their ancestral house sits in Kabir Chaura, where the ghostly melodies play to the sounds of the tabla, sarangi and ghunghroo. The boys trained in the Banaras Gharana under their granduncle Bade Ramdas Ji Mishra, father Pt Hanuman Prasad Misra and uncle Pt Gopal Misra.

The eternity of Varanasi pervades their music, just as it veils the grief of valediction in Pt Sajan Misra’s memories. These remembrances define the relationship between the siblings—learning, bonding, and absorbing the world with music. Pt Sajan Misra recollects a concert in Germany “where no one clapped”. He says, “It was a full house. We chose soft ragas. The silence was so overwhelming that it almost felt like a trance.” After the first half of the performance, they went to the green room for a break. Rajan mentioned that though the programme was progressing well, no one was applauding.

They were a little concerned. While they were discussing the matter, some members of the audience came in. They told the Misras that it was better to announce now that no one must clap even after the recital was over. Rajan asked for the reason. The reply stunned them. Remembers Sajan, “The harmony we had created with the music was so powerful and intense that the audience wanted to retain the feeling in silence even after our performance was over. They felt that clapping would break that harmony.” The maestro remembers that his elder brother often gave the audience the same advice during later concerts. He would request them to voice their appreciation rather than clap after the music stopped.

“We had been singing together since childhood—54 years. I’m fortunate that he was my guide in my musical journey,” says Pt Sajan Misra. “Whenever I sang well, he would always make it a point to give me some money as a token of his blessings,” he adds. Born five years apart, the brothers lived in a joint family. Recalls the bereaved brother, “His room was just above mine. I always felt that his blessings were being showered on me.” He believes the reason their music never palled was that they lived in the moment without mulling over the past. Nor did they worry about the future.

The art of the duet is a difficult one, says the maestro. There are few classical musicians who can pull off a jugalbandi perfectly. Music historians note that the first classical duet was performed by Gopal Nayak and Amir Khusrau together in front of Allauddin Khilji in 1294— Nayak played the veena in the Carnatic style and Khusrau, of course, performed Hindustani classical on the sitar; the latter is given the credit for inventing the sitar for Hindustani classical music. The reason the Misra brothers sang in harmony was “understanding and love for each other”.

The younger Misra says that he believed in surrendering to his elder brother and never competed while singing. It was always complementary. “Therefore, the songs sounded so beautiful and often the audience could not make out who among us two was the one singing. When we sang, we became a single soul singing with two bodies,” he smiles. The Banaras Gharana is unique for incorporating all elements of Hindustani music—dhrupad, dhamar, khayal, chand, prabandh, thumri, chaiti and kajri. The Misras, however, chose to focus on the khayal and became its foremost exponents.

The reason seems symbolic because the song in the khayal musical form is sung in two recurring parts—first the slow (vilambit) khayal segueing into the shorter, fast (dhrut) khayal in the same raga. The brothers complemented each other as both dhrut and vilambit. Khayal, too, is attributed to Khusrau.

Is Pt Sajan Misra desolate? The singer smiles sadly, “My brother left us suddenly. But he has only given up his mortal body.

His soul is still with us. I see him in his children Ritesh, Rajnish, and my son Swaransh.” The singer hopes that the generation gap can be bridged as a tribute to Pt Rajan Misra. “We hope to sing together someday. Music is the true healer,” he says. Any Hindustani classical concerts start with the Bhairav and ends with the Bhairavi. Pt Rajan Misra’s farewell is not when the music stopped. His brother and music partner Pt Sajan Misra is certain that his son and nephews will carry the family legacy forward.

Rajan occupies his brother’s mind. Rajan the intellectual. Rajan the composer. Rajan the interpreter of nuances.