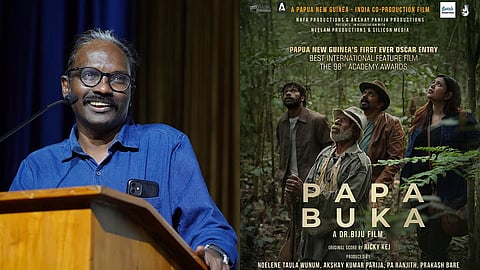

The special screening of Papa Buka at Chavara Cultural Centre on Monday evening, organised by the Cochin Film Society, felt like an invitation into a shared act of remembrance. Directed by acclaimed Malayalam filmmaker Dr Biju (Bijukumar Damodaran), the film arrived in Kochi after a significant international journey.

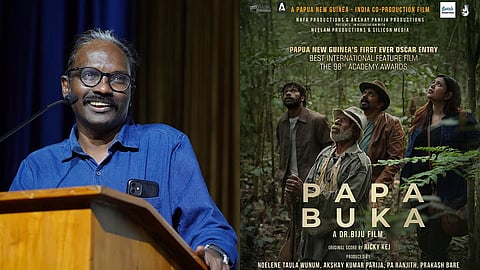

It had its international premiere at the Minsk International Film Festival in Belarus, followed by its Asian premiere at the 56th International Film Festival of India, and was later screened at the 30th International Film Festival of Kerala. Adding to its milestones, Papa Buka was selected as Papua New Guinea’s (PNG) first-ever official submission to the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film at the 98th Academy Awards.

A rare collaboration between India and PNG, Papa Buka revisits a forgotten chapter of World War II, when indigenous Papuans and Indian soldiers were drawn into a distant conflict that was never truly theirs. The film follows two Indians, Romila Chatterjee (Ritabhari Chakraborty), a Bengali researcher, and Anand Kunjiraman (Prakash Bare), a Malayali historian from a marginalised community, as they travel across PNG in search of unacknowledged wartime histories. Guiding them is the titular Papa Buka (Sine Boboro), an elderly PNG war veteran whose memory serves as the narrative's anchor. Rather than staging battles, the film delves into memory, loss, and the quiet aftermath of war.

In this reflective conversation, Dr Biju speaks about the making of Papa Buka, its political and emotional undercurrents, the challenges facing independent cinema, the importance of holding on to one’s convictions, his upcoming film and more.

Excerpts:

How did the initial thought process for Papa Buka take shape?

When we began planning the film with the people of Papua New Guinea, we were looking for a shared historical link between our countries. That search led us to World War II and, more specifically, to the Indian soldiers who died there. We studied records related to the Commonwealth War Graves and gradually developed a narrative thread. Once that historical base was clear, we built a fictional story around it, staying true to the emotional truth of that history. The name Papa Buka came much later, but from the very beginning, the idea was to centre the story on an aged war veteran who acts as a guide to two historians from India. That perspective shaped the entire narrative.

The Bengali researcher character Romila feels very specific...

Historically, a large number of Indian soldiers who went to Papua New Guinea during World War II were from Bengal, more so than from Punjab. That is why the historian was conceived as a Bengali character. It emerged naturally from our research.

Unlike most war dramas today, your film consciously avoids depicting violence. Why did you make that choice?

To show the devastating effects of war, it is not necessary to depict violence explicitly. Violence is the easier route. What interested me more was portraying how war affects people emotionally, through memories, trauma and lingering scars. We wanted to convey suffering without spectacle. Treating war without violence is harder, but it allows for deeper emotional and artistic engagement. When films depend on violent images to convey horror, they start resembling the war they claim to criticise. In the process, there is little difference between those who fight wars and those who turn them into a spectacle on screen.

The casting of Sine Boboro as Papa Buka adds immense authenticity. How did you arrive at casting him?

Casting Papa Buka was indeed challenging. Most elderly people who fit the character live deep inside forest regions rather than in cities. We met about five or six people, but nothing worked until we came across Sine Boboro. We did not ask him to act. We simply asked him to talk, to behave naturally and to be himself. That was enough. He has never watched a film or even a television serial. He does not know what cinema is. He is a tribal leader living in a forest village, and that reality is what the camera captures.

Though rooted in Papua New Guinea, Papa Buka subtly mirrors the struggles of marginalised communities in India. Was this layering present from the start?

No. That layer emerged in later drafts. The lived experiences of indigenous communities are remarkably similar across the world, differing only in intensity. That realisation helped me connect Anand’s character to the tribal communities in Papua New Guinea. I introduced this secondary layer to strengthen the core narrative.

Themes of caste and identity recur in your work. Do you still feel these issues remain underexplored in Malayalam cinema?

Absolutely. Malayalam films rarely engage meaningfully with caste or issues of marginalised communities. When they do, it is often superficial, limited to a scene or two. Compared to Tamil cinema, where even mainstream films address caste directly, Malayalam cinema lags far behind. Even many so-called arthouse films are often pretentious rather than honest. That is the unfortunate reality.

Despite international and national recognition, your films are often labelled as niche or inaccessible. Does that still disappoint you?

That phase is over for me. I felt that disappointment early on, but not anymore. After making ten to fifteen films that receive recognition outside Kerala but not within the state, you realise there is little you can change. We continue engaging with international festivals and global audiences. That is where our space exists.

You have consistently adhered to your own cinematic grammar. Where does that conviction come from?

That consistency actually creates space and opportunity. When our films travel to A-category international festivals, they must speak a universal cinematic language. Fourteen of my fifteen films have been screened at such festivals, which is not insignificant. That recognition comes from staying true to a grammar that aligns with world cinema.

In a fast-moving world with shorter attention spans, do you feel opportunities for independent filmmaking are shrinking?

Yes, especially in Malayalam cinema. There are fewer meaningful films now, and most filmmakers are moving towards medium-scale and safer projects. Political and experimental films receive very little support from the government, the industry or even audiences. Theatre space itself has become inaccessible, making it harder to reach even the small number of viewers who are interested.

The OTT space was once seen as an alternative. Has that changed?

Completely. OTT platforms now cater almost exclusively to films that succeed theatrically. Even films that premiere at major international festivals struggle to find space. Ironically, films from other countries have better access than ours. In India, OTT has become another extension of the mainstream, which is deeply disappointing.

What would you say to young filmmakers who aspire to make politically and artistically driven cinema today?

It is extremely difficult, but they must hold on to their convictions. Ideology, politics and visual language matter. Most filmmakers abandon these after their first setback and shift to conventional narratives. Survival demands courage, the courage to fail, to face economic and critical setbacks and still remain honest to one’s beliefs.

You have described Papa Buka as the second instalment of your war trilogy, following Adrishya Jalakangal. Have you started working on the final film of the series?

Yes. My next film Beyond the Border Lines will complete the trilogy. It is co-produced by Manju Warrier, who also plays the lead. It is an international project with actors from multiple countries and is set along the Indo-China border. Its production requires careful planning, and we are aiming to begin sometime in the middle of this year.