After a cobra bit Rajinikanth, despite the best doctors working tirelessly, they couldn't save the cobra. This is one of the jokes I heard, or helped make in school. I wouldn't know. For Rajinikanth jokes, like his myth, were community property, passed through school corridors like contraband comics. They defied logic because Rajini himself never needed sunscreen to protect himself against the harsh glare of logic or reason: the imagination of his fans was his shield. This joke, I just made up. Call it yours. Copyleft!

I grew up in the 1980s, stumbling into my teens as the last millennium gasped its final decade. We didn't need phones to distract us; we built our own distractions. Our finest invention? Rajini jokes.

Perception back then was Bollywood's heartthrobs made girls sigh: Aamir's coy peck on Pooja Bhatt's shoulder, Salman's brooding dosti ka usool, but we small-town boys in Ankleshwar, Gujarat, as in hundreds of small towns of India, knew the real currency: a well-timed Rajini joke. The senior-class girls (since all classmates were rakhi-bound to you) only noticed you if you cracked one. Hasi toh phasi? Never. Our creed was Hasi toh baat badhi; laughter was collateral, humour was our social leverage.

I remember a boy from the lower grades lobbing this grenade: When Rajini lost a little blood killing the Dead Sea, the Red Sea had to be emptied to replace it. Hai? The studious girl blinked, the joke flying over her head like a well-timed Malcolm Marshall bouncer. The tot's attempt at cracking a joke on his senior didn't crack her up, but us boys laughed at him for the rest of the school year. That's the power of a Rajini joke: Comes with a one-year warranty.

We lack frivolous sociology Ph.D.s. If we didn’t, someone would surely have dissected the Rajini Paradox: What came first—the physics-defying stunts or his jokes. Like the chicken-or-egg mystery, God doesn't know because Rajini sir won't tell the truth of either. I can still feel my incredulity when a South Indian classmate, having seen the latest Rajini film on a pirated VHS tape smuggled not from Chennai or Hyderabad, but Dubai, told me of what Rajini did in it: kill two goons with one bullet after firing the bullet first and splitting it with a knife.

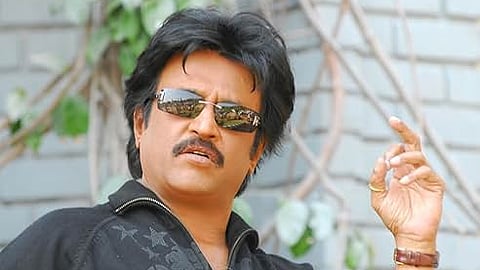

Our childhood minds marinated in a delicious disbelief. Of course, he could. It's Thalaivar. He can do anything: toss a cigarette, shoot it alight, and catch it between his lips as goons gape, even spin spectacles by their arms to land perfectly on his nose. We all mimicked that one. Easy-peasy, we thought. The girls giggled at our shattered frames.

I didn't know then that this persona—Bruce Lee's fury, Chuck Norris' swagger, Amitabh's chutzpah—was engineered, coincidentally yet carefully. Rajini credits Bachchan, but he should thank Salim-Javed's Angry Young Man. He reinterpreted that rage for the South: 11 Bachchan remakes in Tamil, several being Salim-Javed scripts, yet each radiating with a kinetic energy wholly his own.

Here, in this translation of Amitabh's channelling of everyman's anger through his tall, lean frame, into Rajini's smiling dynamism, was born the phenomenon. The one that bored office workers and schoolkids alike was weaponised into jokes and tall tales capable of haunting Einstein's ghost.

For me, Amitabh embodied the 70s, the nation's rage against Nehruvian promises gone sour. Rajini? He was the confused catharsis that followed. The 80s and early 90s were India's purgatory: corruption festered, anger curdled into apathy, and we drifted, waiting without knowing what we waited for—until the license raj died with the Soviet bloc, and new channels flooded our airwaves.

That limbo of a nowhere time, in nowhere towns like Ankleshwar of the somewhere country of India, was filled up by the stunts and jokes of Rajini. We were all Trishanku—suspended between heaven and earth, cynicism and hope—entertained by a god masquerading as a movie star.

Fifty years since Rajini sir first faced the camera, how do I, a Bollywood-fed kid denied his Southern movies, define him? You had to be there in the 1980s and '90s: breathing the dust, trading those jokes, feeling the absurdity of an era where only the impossible felt real, to truly understand what it really meant for us. He wasn't a phenomenon. Not a person. Not even a superstar.

He was the punchline to India's cosmic joke, the one where we laughed through the chaos, knowing that while heroes fade, legends twist gravity. And when Death finally comes for Rajinikanth? He'll just reboot the universe and make it his origin story.