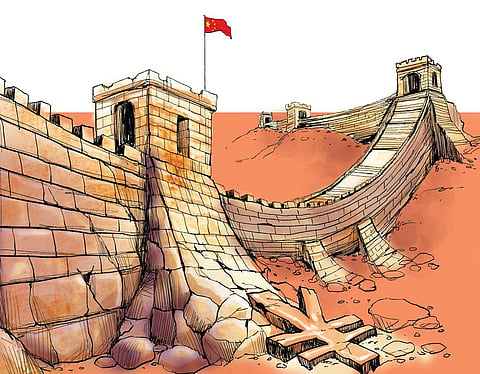

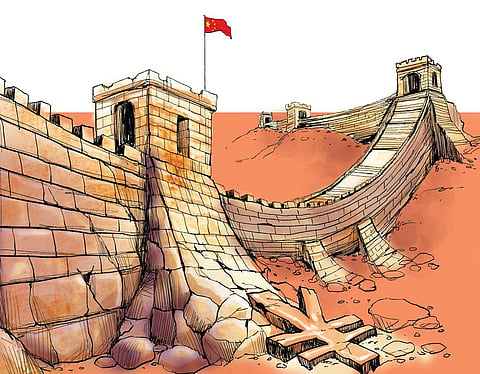

NEW DELHI: The Great Wall of China—its economy—is in tatters. Analysts of all hues and colours are busy writing epitaphs of the Chinese economy, which was hitherto considered unstoppable. They believe the 40-year march of the Chinese economy has already halted and gone into a long hibernation like the one experienced by its neighbour Japan from the 1990s till recently.

There are ample tell-tale signs of the Chinese economy powering down. In 2022, the GDP grew just 3 per cent against the official target of 5.5 per cent. In the same year, the net foreign direct investment (FDI) flow to the country more than halved to USD 180 billion from USD 344 billion in 2021. Also, the FDI inflow in 2022 was the lowest in five years.

The cracks have become much more visible in 2023, forcing some analysts to moderate their GDP growth projections to 4.5 per cent from earlier estimates of 5.5 per cent growth. In the first six months of 2023, net FDI fell 3 per cent year-on-year to USD 98 billion. China’s exports shrank 14.5 per cent in July while imports fell 12.4 per cent compared to the year-ago period.

On a year-to-date basis, China’s exports for the first seven months of the year slipped 5 per cent from a year ago, while imports dropped 7.6 per cent in the same period. The last straw, however, was the jobs data. China’s youth unemployment rate hit a disturbing high of 21.3 per cent in June. After this, China decided to stop releasing the official unemployment data altogether.

What exactly led to this situation, which was unimaginable till a couple of years ago? It seems the three great strengths of China — its polity, population, and an unquenchable thirst for infrastructure spending – are the reasons for its undoing.

Borrowing binge

Since the early 1980s, China’s growth story has been marked by unprecedented investment in the creation of public infrastructure, cities, and towns. The country’s leadership made conscious efforts to move a large number of its population from villages to cities. In 1980, only 20 per cent of China’s population used to reside in urban centres. Now, almost two-thirds of its population lives in cities. That’s no mean feat if one compares this with India’s numbers – in 1980, a little over 23 per cent of the population used to reside in urban areas. Now, even after 43 years later, India’s urban population has grown only to 36 per cent.

China achieved the massive urban shift by investing heavily on infrastructure, housing, and other physical assets. Needless to say, much of this investment was made using borrowed money. The Chinese government encouraged local governments in provinces, corporates, and even households to borrow generously and invest heavily in physical assets. This kicked off a borrowing binge in the country, which is now saddled with a debt that is a mammoth 300 per cent of its GDP -- one of the highest in the world. While government debt at 82 per cent of the GDP remains moderate, household and corporate debts, which have exceeded 200 per cent of the GDP, are the bigger problem for the country. Overspending has not just led to the rise in debt levels but also resulted in under-used, unproductive, and unnecessary infrastructure.

Realty bubble

By now, all of us would have heard about China’s ‘ghost cities’ and ‘ghost factories’. According to many reports and estimates, around 65 million homes in different Chinese cities remain unoccupied. The vacancy rate in China is 12 per cent, second only to Japan (with a 13 per cent vacancy rate). Large parts of many Chinese cities with connected roads, public spaces, and skyscrapers remain uninhabited. A Wall Street Journal report cited an example of the country’s excessive infrastructure overspending. The report talks about one of China’s poorest provinces Guizhou, which boasts 1,700 bridges, and 11 airports. The province has a total debt of USD 388 billion, and in April it asked for more finances from the Central government.

Estimates suggest that China’s real estate sector accounts for 30 per cent of the country’s GDP, and 70 per cent of household assets are held in real estate. In India, the numbers are 6-7 per cent and 50 per cent, respectively. With such high reliance on the real estate sector, China finds itself on the cusp of a crisis with two of the country’s large real estate firms—Evergrande and Country Garden—defaulting on debt repayments. The two together owe more than USD 500 billion to their creditors. Evergrande has already sought bankruptcy protection in the US. If either of them collapses under the burden of heavy debt, it could spiral into an uncontrollable debt crisis in China.“Defaults by large property developers outpace regulators’ ability to resolve them, causing investment to plummet, home and apartment sales in China to plunge, and dwelling prices to fall some 20 per cent peak to trough,” says a Moody’s Analytics report.

Political somersault

China’s communist party till a few years ago supported a market-driven economy and private entrepreneurship. But, things are slowly changing ever since President Xi Jinping rose in stature within the party. Xi has begun undoing the legacy of previous regimes since the days of Deng Xiaoping, who embraced the market economy and began the process of great ascent of the Chinese economy. Xi has now undertaken a new set of economic policies with an emphasis on common prosperity, a green economy, and upholding socialist values. The Chinese president has also spoken about correcting the ‘imbalances’ of the past economic policies that have led to unequal growth and increased stratification of the society. The focus now seems to have an increased say on the public sector in the economy, and restrictions on the private sector. The conventional market economic thinking is being side-stepped for more party-led policymaking.

The Chinese government has also hinted at slowing down the breakneck speed at which it was growing in the past and choosing a more long-term sustainable growth model. “We should first consider the size of the population and the large rural-urban development gap. We cannot be ambitious and unrealistic but we cannot simply follow the beaten path,” Xi has been quoted as saying by Qiushi, the official journal of the Chinese Communist Party.

When China began its crackdown on big tech companies in late 2020, commentators wondered if Xi Jinping’s new economic model was finally unfolding. The crackdown started with an unceremonious last-minute calling off of the initial public offering (IPO) of Jack Ma-led Ant Group in November 2020. This was a week after Jack Ma had taken a dig at China’s regulators and banks for holding back the growth of the country’s tech companies. The Chinese authorities, then, pressed ahead with their crackdown. At the annual Central Economic Work Conference in December 2020, they told tech bigwigs including Alibaba, Tencent Holdings and Byte Dance in December 2020 to correct their monopolistic and anti-competitive practices.

Ever since, Chinese regulators have sent notices to over 30 tech companies, many of which were also fined for anti-competitive practices and non-compliances. And, China’s market regulator started the scrutiny of mergers and acquisitions involving the big tech companies dating back to the 2000s. All these measures led to the erosion of trillions of dollars in the market cap of Chinese technology companies. The crackdown that began in 2020 has left the country’s private entrepreneur-led tech sector smaller in stature. Commentators believe Xi is steering the economy towards a more government-administered system, curtailing the private sector and entrepreneurs.

Demographic debacle

China, the world’s second-largest populous country with 1.4 billion people, is fast losing its demographic advantage. China’s population in 2022 dropped for the first time in six decades. The UN estimates the Chinese population to drop to 1.3 billion by 2050. More than its decreasing population, its ageing population is a bigger concern for the country. Those in the working age population (15-64 years) account for 69 per cent of the country’s population, which according to Moody’s is likely to drop 6 percentage points by 2040.

China followed the one-child policy from 1980 till 2016, and while it helped the country keep its population in check, it also created a demographic crisis. It junked the policy in 2016 but it was probably too late. The country’s working-age population, which had peaked in 2011 at 900 million, has been shrinking ever since. By 2050, China’s working-age population might fall to 700 million. According to Brookings, these 700 million working-age population might be supporting 500 million Chinese aged above 60 years, who are currently estimated at 200 million.

With a shrinking working-age population, the country is no longer a home to cheap labour. Per-hour manufacturing labour cost rose to USD 6.5 in 2020 compared to USD 4.82 in Mexico and USD 2.99 in Vietnam. With curbs on the private sector, a shrinking demographic advantage, and an oversized corporate debt, the country has somewhat lost its competitive edge in manufacturing and is unable to attract fresh investments in the sector. As it struggles with structural issues such as high debt, unfavourable demographic shifts, and a policy overhaul by the government, Beijing is staring at growth fatigue. It may be a long winter for China.

Impact on India