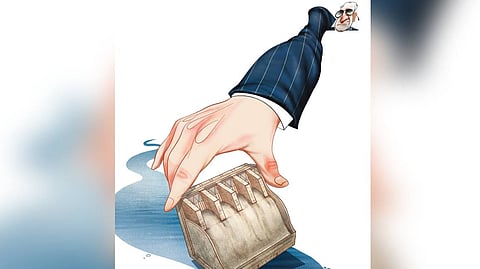

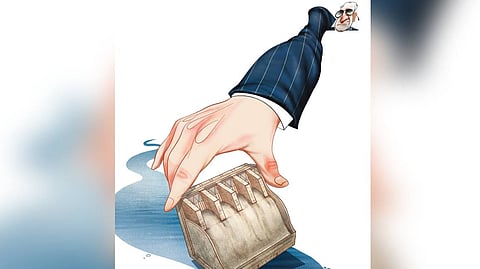

NEW DELHI: It is said that the future wars might be fought for water. The frosty relations between India and Pakistan could see further strain as New Delhi has stepped up pressure on Islamabad for a review of the 64-year-old Indus Water Treaty, which stipulates how the water from six cross-border rivers should be shared between the two countries.

The treaty, brokered by the World Bank and signed by the then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Pakistan’s Field Marshal General Ayub Khan on September 19, 1960 in Karachi, allocates the west-flowing rivers Indus, Jhelum and Chenab to Pakistan and eastern rivers Ravi, Beas and Sutlej to India.

Because of the nature of the original treaty, India has access to only about 20% of the total water covered in the pact with the 80% going to Pakistan. This is because the western rivers have much more water than the east-flowing ones.

India now wants the terms of the treaty reviewed saying the circumstances under which the treaty was signed six decades ago have drastically changed. On August 30, India served a formal notice to Pakistan under Article XII (3) of the pact, which deals with modification of the terms and conditions. It told Pakistan there will be no more meetings of the Permanent Indus Commission till both governments discuss the renegotiation of the treaty. In effect, India put the three-tiered dispute resolution process built into the treaty on pause.

Why review

In its notice to Pakistan, India cited the change in demographics, environmental challenges, and other factors as the rationale behind asking for a reassessment. Also, India’s population exploded over the years and limited access to river water sources has remained a big challenge.

The treaty allows India to develop hydroelectric projects on the western rivers provided they are built on a 'run-of-the-river' basis without significantly altering water flow to the downstream areas in Pakistan. Run-of-the-river projects use the natural downward water flow along with microturbine generators to capture kinetic energy while impounding little water and protecting the interests of lower riparian Pakistan.

However, Pakistan has tried to obstruct India’s Krishnaganga hydroelectric project on the Jhelum and Ratle project on the Chenab claiming these would impact water flow into their territory. India asserted that while the projects do hold some water, they don’t adversely alter the water flow downstream. Pakistan invoked the dispute resolution mechanisms under the treaty multiple times but a full resolution has not been reached.

Dispute resolution mechanisms

Under the treaty, the dispute resolution mechanism is graded. The first level is the Permanent Indus Commission, which comprises a commissioner each from India and Pakistan. This panel is meant to settle minor questions that are mostly technical.

If issues remain unresolved after exhausting this step, then the 'questions' become 'differences' and finally 'disputes'. They may be escalated to the next level, in which a neutral expert is appointed by the World Bank, who acts as the mediator. For example, a neutral expert ruled in favour of the Baglihar run-of-the-river hydroelectric project on the Chenab in J&K despite Pakistan’s objections to the dam’s design.

If the neutral expert fails to resolve the matter satisfactorily, then the third mechanism of a Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague can kick in. In the case of India’s two hydroelectric projects, Pakistan has repeatedly raised objections and approached the Court of Arbitration without exhausting the other dispute resolution mechanisms under the Indus Water Treaty.

Previous notice

This is not the first time that India has notified Pakistan about the need to revisit the treaty. In January 2023, New Delhi sought review citing Islamabad’s 'intransigence' in implementing the treaty, by raising repeated objections to hydro-electric projects on the Indian side.

Welcoming the latest notice to Pakistan, former foreign secretary Harsh Vardhan Shringla said: “The treaty has served its purpose over the last six decades but developments over time warrant a review of the arrangements.”

Pakistan’s stand

In its rebuttal, Pakistan said all discussions could take place within the treaty’s existing framework. Pakistan’s foreign office spokesperson Mumtaz Zahra Baloch said Islamabad is committed to the treaty and the issues could be discussed between the commissioners appointed by both countries. “The Indus Water Treaty is an important treaty that has served both Pakistan and India well over the last several decades. We believe it is the gold standard of bilateral treaties on water sharing and Pakistan is fully committed to its implementation. We expect India to also remain fully committed to the treaty,” Baloch said.

What the treaty says

The preamble of the treaty states, “The Government of India and the Government of Pakistan being equally desirous of attaining the most complete and satisfactory utilisation of waters of the Indus system of rivers and recognising the need, therefore of fixing and delimiting in spirit of goodwill and friendship, the rights and obligations of each in relation to the other concerning the use of these waters and making provision for the settlement in a cooperative spirit.’’

According to India, Pakistan has been intentionally obstructing projects on the Indian side by misusing some provisions of the treaty. In 2016, Pakistan raised objections with the World Bank on the design features of these two projects and sought a settlement through a neutral expert. Later, it withdrew the request and sought adjudication through a Court of Arbitration.

For its part, India moved a separate application asking for the appointment of a neutral expert to deal with the dispute. After negotiations failed, the World Bank accepted the demands of both sides by appointing a neutral expert and the chair of Court of Arbitration in October 2022.

India opposed the decision saying such parallel consideration of the same issues is not allowed under the treaty. However, when the matter came up before the Court of Arbitration, it rejected India’s objections in a July 2023 ruling and appointed itself as the competent authority to consider and determine the dispute raised by Pakistan.

India flatly rejected this fiat. "India cannot be compelled to recognise or participate in illegal and parallel proceedings not envisaged by the treaty," then spokesperson of the External Affairs Ministry Arindam Bagchi said. Ever since, the country has boycotted proceedings in the Court of Arbitration.

“It is a bit contradictory to activate both the neutral expert mechanism and the Court of Arbitration on the same set of issues. Also, a lot has changed between India and Pakistan since the last 60 years – including terrorism from Pakistan being on the ascendant. It is time for a review and modification,” a source said.

What next

India’s loss of patience with Pakistan stems from the neighbour’s sinister moves to block development projects on the Indian side using outdated provisions of the treaty. New Delhi seriously considered walking out of the Indus water pact after the outrageous Pak-backed terror attack on Uri in September 2016.

The attack prompted India to suspend the routine bi-annual talks between the Indus Commissioners of the two countries. “Blood and water cannot flow together,” Prime Minister Narendra Modi said at that time.

Three years later while addressing an election rally in Charkhi Dadri, Modi said, "For the last 70 years, the waters that belonged to India and farmers of Haryana were going to Pakistan. Modi will stop it and bring it to your households."

He added, "This water belongs to farmers of Haryana, Rajasthan and the country, and we will get it. Work towards realisation of this has been started and I am committed towards it. Modi will fight your battle."

Similarly, in the wake of Pulwama terror attack in February 2019, Union minister Nitin Gadkari questioned the logic of letting Pakistan use the water of India's quota despite that neighbour continuing to export terrorism to India.

Experts believe India will continue to salvage the treaty by updating the provisions to address the concerns of the present times. It is the only cross-border water sharing treaty in the region that played an important role in maintaining peace, notwithstanding the wars in 1965 and 1971 – both of which Pakistan lost.

False equivalence

India's demand to modify the treaty now has a climate change component that was not part of the original mandate. Climate change is a major global concern because of the frequency and severity of floods and droughts, melting of glaciers, and reduction of river water flows. Add to that population stress and the demand for water keeps growing on either side of the border.

The other point India has made is about Pakistan continuing to export terror into Kashmir through its non-state actors from across the border. Since protection of India's security interests is paramount, water could well become an instrument of coercion if push comes to shove.

Hobbled as his country already is due to terror attacks from elements having sanctuary in Afghanistan and a weak economy, Pakistan Prime Minister Shehbaz recently drew a false equivalence between Kashmir and Palestine. He did so at a time when J&K is experiencing the most peaceful of assembly elections in decades. For example, the Nowhatta area of downtown Srinagar saw people going to polling booths and casting their ballot for the first time in ages in the second phase of elections. Before Article 370 was read down, Nowhatta was a stronghold of terrorists and separatists, who induced stone pelting on security forces every Friday. All that is history. Now people are participating in the peaceful democratic exercise of the battle of the ballot.

Parallel activation of two mechanisms

In October 2022, the World Bank appointed Michel Lino as the neutral expert and Prof Sean Murphy as Chairman of the Court of Arbitration. It’s logic: The treaty does not empower the World Bank to decide whether one procedure should take precedence over the other

Both independent

The two mechanisms are independent. The treaty vests the authority in both mechanisms to determine their own jurisdiction and competence as well as the power to decide on their rules of procedure. The Bank’s role is to reimburse the remuneration of the neutral expert from amounts paid by India and Pak held in a trust