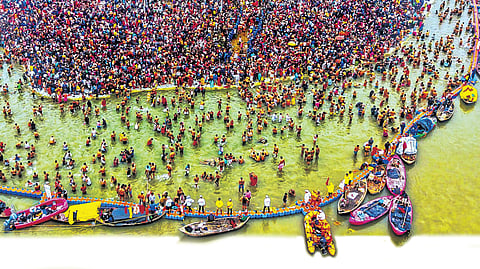

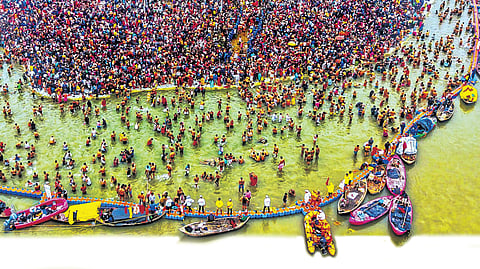

LUCKNOW: The ongoing Maha Kumbh will have the world’s largest human gathering, surpassing even the FIFA World Cup or the Olympics in attendance. While FIFA’s event saw 35 lakh attendees over 40 days, and the Olympics 1.1 crore in 18 days, the Maha Kumbh is expected to draw 45 crore people over 44 days, from January 13 to February 26 this year.

While it is a humongous challenge for the authorities to manage such large crowds—at least 30 people were killed and 60 injured in a stampede on January 29 in Prayagraj—the Maha Kumbh Mela is not just about size. It is about convergence of faith, culture and heritage at the Triveni Sangam, the confluence of the Ganga, Yamuna, and the mythical Saraswati. Here, the ancient civilisation’s spiritual, historical, and scientific facets blend.

The origin

The Maha Kumbh’s origin is steeped in mythology, with the legend of Samudra Manthan (the churning of the ocean) from the Bhagwat and Vishnu Puranas. It describes how gods and demons churned the ocean to retrieve Amrit, the elixir of immortality, with drops falling at four sacred places in India: Haridwar, Prayagraj, Nashik-Trimbakeshwar, and Ujjain.

Each of these sites hosts the Kumbh Mela in a 12-year cycle. Their timing is determined by Jupiter’s 12-year cycle, along with specific Sun and Moon configurations. In Prayagraj, it occurs when Jupiter is in Taurus and both the Sun and Moon are in Capricorn. This Maha Kumbh, being held after 144 years, is significant for several reasons. It began with two extended Shahi (Amrit) Snans on Paush Poornima on January 13 and Makar Sankranti on January 14, and coincided with the Pushya Nakshatra, a planetary alignment. This year’s Maha Kumbh marks the completion of a cycle of 12 Maha Kumbh melas. The last such event was held in 1881.

The Maha Kumbh represents an interplay of Sanatan history, celestial science and geography reflecting how our ancestors perceived the universe as an integral part of life. Among many legends and theories about its origin, the Maha Kumbh finds mention in Vedic scriptures and Puranas.

Mythological references

The Puranas attribute the Maha Kumbh to a curse of Rishi Durwasa, known for his short temper and impulsive curses. As a result of one such curse, legend has it that the gods lost their power and the demons captured heaven. This led Indra, the king of gods, to request Lord Vishnu to free the heaven of demons. Vishnu said the lost fortunes were lying at the bottom of the sea and could be restored only by churning it (Samudra Manthan).

As the legend goes, both the gods and demons engaged in Samudra Manthan which led to the emergence of a whole lot of divine energy including 14 gems, Goddess Lakshmi, and Lord Dhanwantri carrying an ‘Amrit Kumbh’ (a pitcher containing the elixir of immortality). Dhanwantri is believed to be an incarnation of Lord Vishnu and physician of the Devas and God of Ayurveda. On getting their hands on Amrit, both gods and demons staked their claim. The demons snatched the pitcher from Dhanwantri and ran away. While the demons were fleeing, drops of Amrit fell at four different places — Haridwar, Prayagraj, Nashik-Trimbakeshwar and Ujjain.

The gods then pleaded with Vishnu to get back the elixir. Vishnu consented and took the form of Mohini, an enchantress who enticed the demons into submitting to her terms. She made both the gods and demons sit in two separate rows and distributed the elixir among the gods, who consumed it and defeated the demons.

The four spots where the drops of elixir fell acquired a mystical power. It turned the corresponding rivers at these four sites into Amrit at that cosmic moment. These four sites gradually turned into divine locations where pilgrims took a holy dip in the rivers to imbibe the essence of purity, auspiciousness and immortality.

Antiquity of Kumbh Mela

The Skanda Purana has references of the Kumbh Mela. According to many astrologers and students of Sanatan history, and also a book published by Gorakhpur’s Gita Press, called Maha Kumbh Parva, the Kumbh is as old as Rig Veda, which has shlokas mentioning the benefits of participating in it.

However, some believe that it was 8th century Hindu philosopher Adi Shankaracharya who established these four fairs, where Hindu ascetics and scholars could meet, discuss and disseminate ideas of Sanatan. In some treatises, the origins of the Kumbh are linked to the worship of River Ganga as the great force of life in the northern plains.

According to Prof D P Dubey, retired professor of ancient history, Allahabad University, and general secretary of the Society of Pilgrimage Studies, the Kumbh Mela started sometime after the 12th century CE during the Bhakti movement, a movement of the socio-religious reforms by Hindu saints and reformers.

Celebration of life and path to moksha

While many come to the Maha Kumbh for a just dip in the holy river for atonement, some, especially, the kalpwasis, stay at the site for a month for their spiritual evolution by practising religious discipline and austerity. It is believed that taking a holy dip at the Sangam during the Maha Kumbh liberates the soul from the unending cycle of life, death, and rebirth; the soul attains moksha (salvation), considered the ultimate goal of human life.

Auspicious ‘Amrit Snans’

Some days are extremely auspicious for the holy dip, also known as Amrit Snan days. These include Makar Sankranti, Mauni Amavasya and Vasant Panchami apart from three normal snan days: Paush Poornima, Maghi Poornima and Mahashivratri.

Moreover, 13 akharas (monastic orders) comprising thousands of saints and seers set up their camps at the mela and lead processions for taking a holy dip on Amrit Snan days.

Earlier, there used to be a tussle among akharas over leading the Amrit Snans, but now, with a predetermined order for akharas in place, there is no acrimony for bathing rights.

The akharas

The grand celebration of life and faith is also a reflection of the pull of the akharas, deemed the guardians of Sanatan dharma. Akhara means a wrestling arena but in a broader sense, it’s a world comprising many microcosms within. This ecosystem, otherwise relegated to the mutts, comes alive as the backbone of the Maha Kumbh.

Many Vedic researchers believe akharas could be as old as Sanatan dharma. Mythological references claim that demons used to disrupt the religious practices and rituals of seers. Consequently, seers raised a martial wing to guard themselves. Those guarding the seers had to be physically fit, and the place where they practised their art was described as akhara. Considered as a living proof of Sanatan tradition, one cannot imagine the canvas of Kumbh rituals without the akharas.

Adi Shankaracharya

The commonest story of how akharas became a defining element of the Kumbh is linked to Adi Shankaracharya, who is credited with consolidation of the Sanatan tradition in the 8th century. According to Prof Dubey, different sects were believed to be in a constant battle with each other for supremacy, against the purpose and teachings of Hinduism. Adi Shankaracharya brought many of them together by reconciling various sects such as Vaishnavism (followers of Vishnu), Shaivism (followers of Shiva) and Shaktism (followers of Goddess Shakti).

The present form of the Kumbh Mela comes from the structure created by Adi Shankaracharya and therefore many akharas treat him as a father figure.

Categorisation of akharas

The akhara system (see graphic) initially founded with four akharas, grew into 13 by and by. All of them are classified in three major categories — Shaiva, Vaishnava and Udasin.

The Shaiva Akharas comprise the Mahanirvana, Atal, Niranjani, Anand, Juna, Avahan, and Agni sects. The Vaishnava Akharas have Digambara, Nirmohi and Nirvani sects, while the Udasin Akharas comprise Bada Akhara and Naya Akhara. The Nirmal Akhara, which was established on the virtues propagated by Guru Gobind Singh, comes under the Udasin group. All akharas are identified by their flags and dress code.

Akhara Parishad and hierarchy

The first Kumbh in independent India was held in 1954. On Mauni Amavasya that year, an unprecedented crowd descended on the Sangam leading to a stampede that claimed 800 lives and left 2,000 injured. After a probe into the incident, the Akhil Bharatiya Akhara Parishad (ABAP) was formed. Since then, it has been playing an important role in organising the Kumbh Mela. The ABAP includes representatives of all 13 akharas and serves as the apex body of monastic orders. It takes important decisions on the Kumbh and addresses matters related to monastic orders. It also solves disputes (if any) among the akharas.

Vedic scholars attribute the origins of akharas and their way of life to the Sannyasa Upanishads, which focus on renunciation, monastic practice and asceticism. Within each akhara, sadhus are graded into four classes based on their spiritual progress: Kutichak, Bahudak, Hansa and Paramhansa. A Kutichali is a seer living in a forest hut, surviving on unasked alms. A Bahudah is a wandering sadhu collecting alms in kind. Both bear the tridandi title, symbolising control over speech, thought and action.

H S Bhakuni, a faculty member at the department of history, MB Govt PG College in Uttarakhand, says in his paper titled Akhara System in Kumbh Mela that an ascetic is acknowledged after a religious practice of at least 12 years. There is no minimum age for renunciation, and even children could be appointed as ‘mahant’. The paper was published in the International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research.

The Akhara hierarchy includes a spiritual head (Mahamandaleshwar) and administrative units. Ranks include Mandaleshwars, Mahants, Karbaris and others. The administrative body, ‘panch’, comprises five persons, with a president called Sabhapati. Each akhara has its own Naga sadhus and Hatha Yogis.

Naga tradition

The term Naga refers to the practice of renouncing material possessions, including attire, symbolising detachment from worldly life. Draped in ash from head to toe, adorned with intricately braided locks, kohl-lined eyes, many embodying their deity Lord Shiva in all his glory carrying tridents, damrus, and kamandals, Naga sadhus are steeped in mystery.

They trace their roots to ancient India, when ascetics were also warriors entrusted with protection of temples and sacred sites from invaders. Their martial tradition is said to have been formalised by Adi Shankaracharya.

The initiation process is rigorous and can take years for one to become a Naga sadhu. After renouncing worldly pursuits, the aspirant is required to undergo an intense spiritual and physical training under a guru. The training includes meditation, yogic practices, studies of scriptures and martial arts.

Naga sadhus are known for their austere practices, such as meditating in extreme weather conditions, performing penance in caves, forests and secluded places and living a life of celibacy. In their Digambar (unclothed) attire, Naga sadhus undergo a detailed 21-step adornment process to sanctify their body, mind, and spirit while taking the first dip in the Kumbh.

Naga sadhus belong to Shaivite Akharas, such as Juna Akhara, Mahanirvani Akhara, and Niranjani Akhara. These Akharas follow a strict order during the Amrit Snan, with the Naga sadhus taking the lead, emphasising their spiritual and martial legacy. As they are considered to be the disciples of Lord Shiva, they are made to lead the processions for Amrit Snan.

Juna Akhara, the largest and one of the most prominent akharas, includes a significant number of Naga sadhus. Their processions, featuring ornately decorated chariots and religious symbols, are a visual and spiritual delight, embodying the heritage and unity of Sanatan Dharma. Naga sadhus symbolise the essence of spiritual strength. Their participation in the Kumbh serves as a reminder of an eternal quest for moksha (salvation) and the resilience of Sanatan traditions. Their ash-smeared bodies signify mortality and the transient nature of life, while their chants and rituals invoke divine blessings for humanity.

Special provisions are made for their camps, processions, and ritualistic practices, reflecting their status in the Sanatan community. The Maha Kumbh Mela not only celebrates their significant role but also offers an opportunity to the devotees worldwide to witness the legacy of these mystical ascetics and their contribution to Hinduism.

Where do Naga sadhus go after the Kumbh?

For a common man, Naga sadhus are an enigma. As per Ravindra Puri, president of the Akhara Parishad, unlike monks residing in monasteries, Nagas vanish into solitude, returning to caves, forests, and Himalayan retreats to continue with their spiritual endeavours as soon as the Kumbh concludes. They are rarely seen in temples or Akharas across cities.

They prefer to travel at night to avoid public gaze. For them, Kumbh Mela is a rare occasion to emerge from their solitude, connect with the masses and disappear in the pursuit of their spiritual mission.

Aghor philosophy

A surreal and intriguing sight greets visitors at the Aghori camp in the Maha Kumbh. The camp is a huge draw with black clad ascetics, bodies smeared with ash, long unkempt hair flowing down their backs, rudraksha beads adorning their necks, and piercing red eyes. Some don black headgears while others have earrings dangling from their ears, often carrying human skulls as kapalas (bowls). Aghoris are both revered and feared.

The Aghor camps are identified with a large black flag with ‘Alakh Niranjan’ emblazoned on it. This is the enigmatic world of Aghoris, a sect often shrouded in mystery and misunderstanding. Aghoris aim to transcend fear and attachment, seeing life and death as different manifestations of the same existence.

As per an Aghor researcher, for an Aghori, everything is linked to Shiva. They are followers of Lord Shiva, particularly his fierce form as Bhairava. They dedicate their lives to intense spiritual practices aimed at achieving moksha. They believe in the ephemeral existence of life where the body is just a mix of five elements. Through rituals they tend to see beyond dualities like life and death. Their name, derived from the Sanskrit word Aghora, which means non-terrifying or without fear. It reflects their belief in overcoming all forms of fear, attachment and societal norms.

Taboo meets transcendence

Aghors are not bound by Akhara discipline. They believe in the unity of all creation. They view everything in the universe, whether considered pure or impure, as equally sacred. This philosophy leads them to engage in practices that challenge conventional ideas of purity, such as meditating in cremation grounds, consuming what others deem inedible, and embracing what society often shuns.

Their presence at religious congregations like the Maha Kumbh reminds about the deeper spiritual truths of detachment, fearlessness, and the belief that life and death are inseparable.

For a common man, an Aghor is a spiritual powerhouse who can remove obstacles and bring divine grace to life. However, many, intrigued by their persona, struggle to understand their unique way of life.

Some of their practices, such as post-mortem cannibalism (eating flesh from foraged human corpses), are symbolic acts meant to transcend worldly attachments. While these may seem shocking to outsiders, for Aghoris, they are a way of rejecting superficial distinctions and moving closer to enlightenment.

Economic and social impact

Beyond its spiritual significance, the Maha Kumbh invigorates local economies, providing a platform for cultural exchange and unity. It has historically been a venue for social reforms and nationalist movements during India’s struggle for independence, showcasing its role in the socio-political fabric of the nation.

Sequence of Amrit Snan of the 13 Akharas

Shaiva Akharas

Shri Panchayati Akhara Mahanirvani: Committed to spreading the tenets of Sanatan Dharma, with focus on spirituality and service. The akhara was the first to appoint a woman ‘mahamandaleshwar’

Shri Panchayati Atal Akhara: Works to promote ethical and religious virtues. They do not believe in the caste system or Brahminical order

Shri Panchayati Akhara Niranjani: Committed to protecting Sanatan Dharma, with educated seers and strong focus on spirituality

Shri Taponidhi Anand Akhara Panchayat: Unlike other akharas, this one doesn’t follow a protocol. A sanyasi on the lowest level of the ladder can speak his mind freely. It picks learned persons committed to Vedic education and promotion of Indian culture from society and academia to appoint them as Mahamandaleshwar

Shri Panch Dashnam Juna Akhara: Largest and most diverse akhara, known for Naga sanyasis and Hatha Yogis

Shri Panch Dashnam Aawahan Akhara: Known for its Naga sanyasis and Hatha Yogis, with focus on spirituality and service

Shri Panch Dashnam Panch Agni Akhara: Comprises Naishtika Brahmacharis (practice celibacy and live with guru until death) with focus on promoting religion, culture and serving society

Vaishnav Akharas

Akhil Bhartiya Shri Panch Nirmohi Ani Akhara: A key player in the Ram Temple movement, with focus on spirituality and service. Women can rise to become ‘Mahamandaleshwars’ but are not involved in administrative work

Shri Digambar Ani Akhara: Known for its maximum number of Khalsas (equivalent to Mahamandaleshwars) and its commitment to service and spirituality. They believe in service and run ‘langars’ and ‘bhandaras’ during Kumbh

Shri Panch Nirvani Ani Akhara Hanuman Garhi: Stands out for its unique tilak and culture of wrestling and physical fitness. The akhara also has a tradition of Niyudha or fighting without weapons

Udasin Akharas

Shri Panchayati Naya Udasin Akhara: Works to promote Sanatan Dharma and serve society, with focus on education, healthcare, and public welfare

Shri Panchayati Bada Udasin Akhara: Committed to the study of the Vedas, Vedangas, and Ashtanga Yoga, with over 100 ashrams across India

Shri Nirmal Panchayati Akhara: Has close ties with Sikhism, especially Khalsa Sikhs, and is home to Nihang Sikhs