The doctrine of separation of powers must always be acknowledged in a constitutional democracy, the Supreme Court said in its May 15 order ruling that any law made by Parliament or state legislatures cannot be held to be in contempt of court. The decision by a bench of Justices B V Nagarathna and Satish Chandra Sharma came while dismissing a 2012 contempt petition filed by sociologist Nandini Sundar and others against the Chhattisgarh government for enacting the Auxiliary Armed Police Force Act, 2011, alleging the law violated an earlier SC order. The bench held that the law did not amount to contempt of the SC’s 2011 landmark judgment that disbanded the state government-backed Salwa Judum, terming it unconstitutional. Salwa Judum was a government-backed militia formed in Chhattisgarh in 2005, which used armed tribal civilians to combat Maoist violence.

The contempt plea claimed that the Chhattisgarh government failed to comply with the 2011 order to stop open backing of vigilante groups like the Salwa Judum, and instead went ahead and armed tribal youths in the fight against Maoists. It said there had been a clear contempt of the SC order when the state government passed the Chhattisgarh Auxiliary Armed Police Force Act, 2011, which legalised arming tribals in the form of Special Police Officers (SPOs) in the war against Maoists.

The petitioners further submitted that instead of disarming SPOs, which was a key constituent of the SC's 2011 order, the Chhattisgarh government legalised the practice of arming them. They also argued that the victims of the Salwa Judum movement had not been adequately compensated.

In the latest ruling of May 15, the Supreme Court said the Chhattisgarh Auxiliary Armed Police Force Act, 2011 does not constitute a contempt of court per se, and that the balance between sovereign functionaries must always be delicately maintained. “Every State Legislature has plenary powers to pass an enactment and so long as the said enactment has not been declared to be ultra vires the Constitution or, in any way, null and void by a Constitutional Court, the said enactment would have the force of law," the bench said. If any party wants that the legislation be struck down for being unconstitutional, the legal remedies would have to be presented before an appropriate constitutional court, the bench noted.

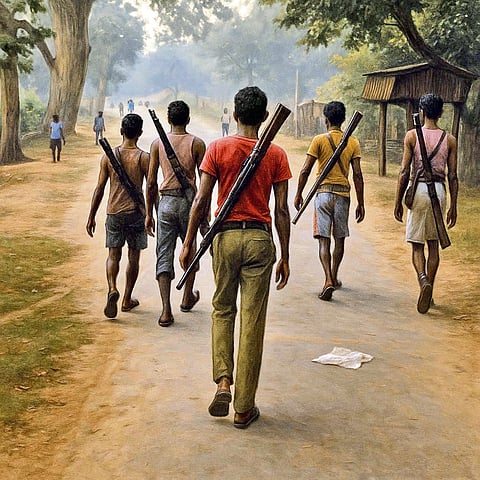

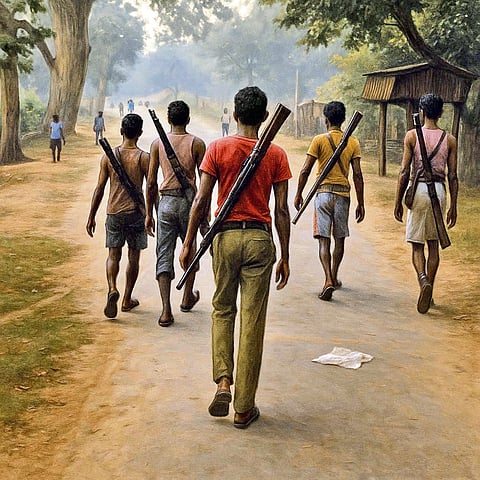

In 2005, Chhattisgarh witnessed the emergence of Salwa Judum, a state-sponsored vigilante movement aimed at countering the Maoist insurgency. The movement, led by Congress MLA Mahendra Karma, was initially supported by local traders and business community, and soon received backing from the state government.

However, Salwa Judum's methods were marked by violence and human rights abuses, with villagers and tribal people being herded into makeshift camps. The movement's actions led to large-scale displacement, with over 100,000 civilians, as per one report, fleeing to camps or neighbouring states. The movement led to significant loss of life and property.

A fact-finding team's account in an essay titled ‘Salwa Judum: War in the Heart of India' by the Independent Citizens Initiative stated that many tribal youths, many unwilling, were drafted in as SPOs for paltry salaries. “Many SPOs complained that while they had been enlisted in the service of the nation to rid the area of Maoist menace, they had not been trained in weapons use and could not even defend themselves let alone rid the area of Maoists. Many were armed with bows and arrows, or with obsolete World War II vintage 303 rifles. The government was unwilling to arm them with better weapons for fear they could fall into the hands of Maoists. On the other hand, they are vulnerable to Maoist counter attacks.”

By 2008, Salwa Judum’s influence began to wane, with the number of people living in camps dwindling and public support decreasing. The group was accused of human rights abuses, including killings, abductions, and rapes. The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), which launched the fact-finding mission, said the movement had lost momentum, restricting itself to 23 camps in Dantewada and Bijapur districts. Chhattisgarh police's experiment to employ tribal youths as SPOs, or Koya Commandos, seemed to have backfired.

In its February 2011 judgment, the Supreme Court declared Salwa Judum as illegal and ordered that the movement be disbanded. The court also directed the state to cease using SPOs in any form or manner, recall all firearms issued to SPOs, provide security and protection to affected communities, and investigate and prosecute instances of human rights abuses.

The SC’s ruling came during the hearing of a petition filed by Nandini Sunder, Ramachandra Guha, and E A S Sarma, alleging widespread human rights violations by Salwa Judum in Dantewada district. The court considered allegations of gross human rights violations, including the burning of villages, rape, and murder. Swami Agnivesh, a social activist, had alleged that 300 houses were burnt down in three villages, women were raped and men killed. The court noted that the state's response to these allegations was inadequate. This apart, the court also questioned the nature of training, control, and accountability of SPOs, apart from the fact that the state's affidavit revealed that 1,200 SPOs had been suspended and FIRs registered against 22 SPOs for criminal acts, pointing towards grave human rights violations.

Months after the Supreme Court's verdict, Chhattisgarh passed the Auxiliary Armed Police Force Act in September 2011 to create an additional armed police force drawn chiefly from the tribal populace. This outfit was intended to aid and assist regular security forces in maintaining public order and combating Maoist violence and insurgency within the state.

The passage of the Act was contentious, following the Supreme Court order to disband groups like Salwa Judum. Critics argued that it circumvented the SC order by legalising existing SPOs.

By providing a legal basis for the recruitment, training, and deployment of the auxiliary armed police force, the Act empowered the state government to establish a more robust and legally sanctioned framework for auxiliary policing in Chhattisgarh. According to the state government, the law aims to address Naxalite/Maoist insurgency and maintain public order, ultimately enhancing the state's ability to tackle security challenges.

The Supreme Court’s May 15 ruling has removed the legal challenge to Chhattisgarh’s 2011 law, for now.