India placed the 65-year-old Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) in abeyance after the horrific April 22 terror attack in Pahalgam where 25 male tourists from 14 different states were selectively killed on the basis of their religion. The massacre shook every moral fibre of the otherwise polarised polity in the country and beyond, uniting them in anger and grief.

As Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Omar Abdullah eloquently said in a special session of the state assembly, “This was not just an attack on people from one state — it was an attack on the very soul of India. The victims hailed from across India, from Arunachal Pradesh to Gujarat, from Kerala to J&K. The whole country has been affected by this attack.” J&K observed a total bandh against terror for the first time in decades, as the attack emptied it of its main source of revenue at the peak of the tourist season. The carnage prompted the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS), the country's apex national security body, to weaponise the IWT and put it on hold till “Pakistan credibly and irrevocably abjures its support for cross-border terrorism.” It was among a raft of other measures to put the enemy on the mat.

In the first official communication after the CCS decision, Debashree Mukherjee, Secretary of the Ministry of Jal Shakti, Government of India, wrote to her Pakistani counterpart Syed Ali Murtza, on the need to reassess obligations under the IWT. She said the fundamental circumstances that led to the establishment of the IWT had changed significantly, requiring discussion and renegotiation. She referred to the altered population demographics, necessity for clean energy, and other factors arising from climate change that affect water-sharing assumptions. Additionally, the letter stated that the treaty was initially established in good faith, which has been consistently undermined, resulting in India’s inability to fully utilise its rights under the pact.

This was not the first notice sent to Pakistan on the matter. In January 2023, India first communicated its intention to amend the IWT as Pakistan failed to adhere to the dispute resolution mechanism built into the treaty; instead, it unilaterally approached the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague complaining about two hydropower projects in J&K — the Kishanganga and Ratle. In September 2024, India sent another notice to Pakistan, again highlighting the fundamental changes in circumstances that necessitated a review of the treaty.

During the British Raj, a complex canal system was built to irrigate Punjab. After Partition in 1947, control over major canal head points mostly remained with India, particularly at Ferozepur in Punjab. In 1948, India temporarily halted the flow of water to Pakistan, which heightened concerns in Islamabad about a potential agricultural collapse. It sought the assistance of negotiators involved in the Partition of the land, including Lord Mountbatten, on several occasions to seek an equitable treaty for the lower riparian state that would make India accountable for water flow. But since the UK had lost its colonial sway after World War II, the United States intervened, encouraging the newly independent India and Pakistan to engage in negotiations. In 1955, the US worked with the World Bank to facilitate these discussions, ultimately leading to an agreement in 1960.

A fact sheet put out by the World Bank says the IWT was signed on September 19, 1960 after nine years of negotiations. India and Pakistan and the World Bank are signatories to the treaty. In other words, the World Bank came into the picture four years before the US prodded it to do so.

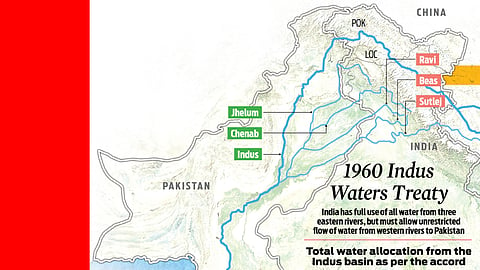

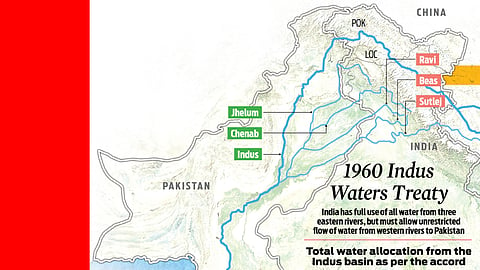

Under the treaty, Pakistan was given waters of three western rivers — Jhelum, Chenab and Indus — while India got absolute control of waters of eastern rivers — Satluj, Beas and Ravi. The western rivers provide a total of 80 million acre-feet (MAF) of water, of which India can use only up to 3.6 MAF for non-consumptive purposes, which include irrigation, drinking water supply, navigation, and hydropower generation without changing the course of the river.

India got full control over the eastern rivers, which have a total of 33 MAF water. The country has utilised almost its entire share of the eastern river system through the Bhakra-Nangal Dam, Ranjit Sagar Dam, Pong Dam, and the long canal network.

When the IWT was signed, several important factors were not fully considered. At that time, negotiators had a limited understanding of climate change and the impacts of groundwater depletion, water pollution from pesticide and fertilizer use, and industrial waste. Additionally, the treaty largely overlooked the potential for future dam projects, renewable energy developments and canal construction.

The IWT was designed in a different global context, where it was viewed as a fair and effective solution. It has proven resilient, having survived three full-scale wars between two nuclear nations. At the time of the treaty's signing, Pakistan's population was around 46 million, while India's was 436 million. By 2025, these figures have changed dramatically; Pakistan's population is now over 240 million, and India's exceeds 1.4 billion. The rapid population growth and increasing urbanisation have placed immense pressure on water resources, necessitating more drinking water and electricity generation.

As the world strives to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, there is a critical need to ramp up the global renewable energy capacity. This transition must include a higher mix of renewable sources such as solar, wind, hydropower, and nuclear energy. Studies indicate that approximately 850 GW of new hydropower capacity will be needed by 2050 to keep global warming below 2°C, underscoring the importance of hydropower in achieving climate goals. India shares the burden of decarbonising its economy and is ambitious about increasing its renewable energy capacity, including hydropower.

Currently, India has a renewable energy capacity of 150 GW, with 33% hydropower component. To meet its target of net-zero emissions by 2070, India aims to achieve 500 GW of non-fossil fuel-based energy. This entails doubling its current hydropower generation capacity from over 50 GW to 100 GW. The rivers in the Indus Water Basin will play a crucial role in this effort. According to potential studies by the Ministry of Jal Shakti, India can harness up to 20,000 MW (20 GW) of power under the IWT.

However, the treaty restricts India’s ability to utilise its own legal water and makes run-of-the-river projects less effective. Experts indicate that the treaty grants India rights to 3.6 million acre-feet of water, but Pakistan has not allowed India to use it effectively. For instance, in the Baglihar Hydroelectric Power Project, a run-of-the-river power plant on the Chenab, India aimed to legally store water up to 25 million cubic meters (MCM), but its capacity was reduced after Pakistan sought World Bank intervention.

Additionally, a significant provision of the treaty stipulates that the outlets of projects must be positioned higher, leading to increased siltation and rendering current projects less effective. (See box)

The impacts of global warming and ongoing support for terrorism in Kashmir have further exacerbated tensions. At the time of the treaty’s discussions, negotiators did not consider how global warming would affect glacier mass balance in the region, resulting in decreased water flow in the basins. A recent report by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) highlighted that global warming has led to lower snow persistence in the Hindu Kush Himalaya, of which the Indus Basin is a part. The region has experienced the lowest snow persistence in the past two decades, and various studies indicate that the glaciers feeding the Indus Basin are melting at an accelerated rate.

Following the Pahalgam attack and India putting the IWT in abeyance, Chief Minister Omar Abdullah described the treaty as the most unfair document for the people of J&K. Experts argue that the treaty was negotiated with the country's best interests in mind but it has prevented J&K from using its own water resources. Over time, the econ omic aspirations of J&K have increased. The government aims to negotiate a revised treaty to better address these aspirations and grant the region a fair share of water resources.