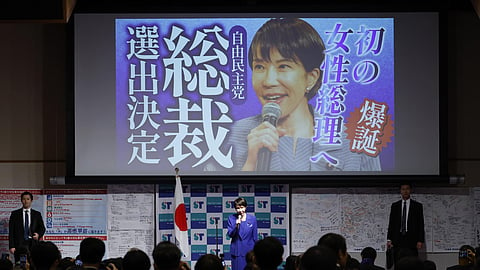

Japan is once again on the verge of a political shift. With the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) electing Sanae Takaichi as its new leader, the country could soon see its first female prime minister.

Takaichi’s rise comes on the heels of Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba’s resignation after just over a year in office, following two major electoral defeats that cost the LDP its majority in both houses of Parliament.

While Takaichi’s leadership marks a potential milestone in gender representation, it also underscores a deeper pattern: Japan’s revolving door of prime ministers. Despite its reputation for social stability, Japan has an unusually high rate of leadership turnover compared to other developed democracies around the world.

Why does Japan change prime ministers so frequently—and what does this mean for the country’s political system?

The long reign of the LDP — and the cost of dominance

Since 1955, Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party has dominated national politics, governing almost continuously for nearly seven decades. It was formed from the merger of two conservative parties in response to a rising post-war socialist movement. Many hoped this would evolve into a stable two-party democracy.

Instead, the LDP’s grip on power became so entrenched that Japan came to be seen as a “one-and-a-half-party system”, where the main opposition, the Japan Socialist Party (JSP), rarely posed a serious electoral challenge.

A similar dynamic played out in Italy during the Cold War era, where the Christian Democratic Party ruled almost uninterrupted, while the Communist Party remained the perpetual runner-up. Both countries shared long-term single-party dominance and a pattern of frequent leadership changes within the ruling party.

This paradox of political dominance by a single party combined with constant leadership churn is central to understanding Japan’s political instability at the executive level.

Electoral reform and the hope for change

In the early 1990s, growing dissatisfaction with corruption and stagnation led to electoral reforms. Japan introduced a mixed electoral system combining single-member districts and proportional representation, modeled in part to encourage a two-party system.

The goal was to bring accountability to government by increasing the chances of opposition parties winning, while strengthening the prime minister’s mandate. While this system did lead to some competitive elections and even brief transfers of power such as the Democratic Party of Japan’s (DPJ) win in 2009 the structural dominance of the LDP remained largely intact.

What didn’t change, however, was the pattern of frequent resignations. Since 1993, Japan has cycled through 13 prime ministers and many of them served less than a year. By comparison, Germany has had just three chancellors in that same period.

Why does Japan struggle to keep leaders in office?

One major reason lies in the architecture of Japan’s bicameral legislature, especially the power of the House of Councillors (upper house). While Japan’s Constitution makes the lower house (House of Representatives) superior in matters of legislation, a rejected bill can only be overridden with a two-thirds majority in the lower house — a high bar.

As a result, when the ruling party lacks control of the upper house — a scenario known as “divided government” — it becomes significantly harder to govern. In these cases, legislative deadlock, political brinkmanship, and public frustration all tend to rise, weakening the prime minister’s standing and often triggering resignations.

For example, in 1998, after the LDP lost an upper house election, Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto was forced to step down despite holding the lower house majority. More recently, leaders like Abe Shinzō (during his first term), Fukuda Yasuo, and Kan Naoto were all pushed out during periods of divided government.

However, the upper house alone doesn’t explain everything. Leaders like Yoshir Mori (2000-01) and Yukio Hatoyama (2009-10) stepped down even with relatively stable parliamentary control.

Clearly, other factors are at play.

Factionalism within LDP

The LDP is not a unified ideological bloc but a collection of factions — informal, often competing power groups within the party. While factional politics have declined in influence since their heyday in the 1970s and 1980s, they still shape leadership contests and policymaking.

Prime ministers must constantly navigate these internal dynamics to survive. Unlike in more presidential-style systems, Japanese prime ministers are more dependent on party consensus and backroom support than on popular mandates.

When approval ratings dip — either due to economic missteps, scandals, or international miscalculations — factions may quickly withdraw their support, setting the stage for leadership changes.

This is what happened with Ishiba, who lost internal support after poor electoral showings and was forced out before a formal challenge could even be mounted. The new leader, Takaichi, inherits not just the position but the same unstable foundation.

Cultural expectations and public sentiment

Japan’s political culture places a high value on consensus and accountability. When a government loses an election or a major policy initiative fails, resignation is often seen as the honourable course of action — even if the political stakes are not existential.

This cultural expectation contributes to the speed with which Japanese leaders step aside after setbacks. In other countries, such as the US or UK, leaders often weather scandals and policy defeats without resigning. In Japan, even minor missteps can create pressure to leave office, especially if public opinion turns sharply negative.

Additionally, Japan’s media and electorate tend to demand immediate political accountability — which, in practice, translates into frequent leadership turnovers.

Coalition complexity and fragile mandates

Although the LDP has usually governed alone or as the senior partner in coalitions, Japan's multi-party environment means that even large parties must often rely on smaller partners to pass legislation. This adds complexity to governance and can limit a prime minister’s ability to enact their agenda.

Coalition politics in Japan tend to be less fragmented. But the reliance on junior parties like Komeito still forces the prime minister to compromise, adjust policy direction, or abandon unpopular plans.

This fragile mandate, combined with a lack of presidential-style executive authority, makes it easier for party insiders or coalition partners to unseat a leader who loses popularity or policy momentum.

What Takaichi faces now

Sanae Takaichi takes the reins at a moment of considerable uncertainty. She inherits an economy burdened by low growth, inflation, and demographic challenges. Japan’s global positioning is also in flux, especially amid a more transactional approach from Washington under Trump and intensifying regional tensions with China and North Korea.

Most importantly, she must unify a party that has been rocked by scandals, fractured by factional infighting, and weakened at the ballot box. If confirmed as prime minister, Takaichi will face the same structural constraints and institutional volatility that forced out so many of her predecessors.

Her success will depend not just on policy decisions, but on her ability to manage internal party politics, navigate divided government, and respond to shifting public expectations — all within a system that seems almost designed to topple its leaders.

For now, all eyes are on Takaichi, whose leadership may be historic. But she is unlikely to be immune from the forces that have undone so many before her.