DHARMAPURI: A cross the forested hills of northern Tamil Nadu, fragments of an ancient world lie scattered, half-buried hero stones, fading rock art and stories that survive only in the memories of tribal elders. As these traces face erasure from quarrying, encroachment and indifference, one man has made it his life’s mission to rescue them from oblivion.

Dr C Chandrasekar, a 52-year-old associate professor at Dharmapuri Government Arts College, is working against time to preserve the vanishing legacy of tribal civilisation. From decoding folklore passed down through generations to documenting prehistoric burial sites and unsung hero stones, he has emerged as one of the most committed chroniclers of TN’s lesser-known past.

What began as academic curiosity has grown into sustained work on the ground. Travelling through remote hamlets and forest interiors, Chandrasekar gathers oral histories narrated by tribal elders, interprets symbols carved on hero stones and maps burial sites increasingly threatened by neglect and commercial activity.

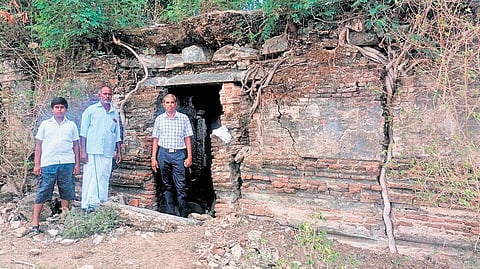

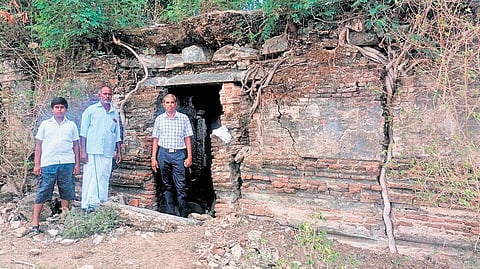

Through Thonmam Varalatru Ayivu Arakkattalai (also known as Thonmam Varalaru Kattalai), a collective he founded, he organises field visits, awareness programmes and volunteer-led documentation efforts. The aim, he says, is to instil a sense of ownership among local communities while pressing authorities to protect these fragile remnants of the past.

Reflecting on his fascination with history, Chandrasekar traces it back to his childhood. “It began 40 or 45 years ago. My father worked with the Tamil Nadu Electricity Board and was once tasked with providing hut connections to a tribal hamlet in Sitheri. That was where I first saw rock art, and it captivated me,” he said. “As I interacted with the tribal people, I came across hero stones, cairns and other seemingly mysterious statues. At the time, they felt like stories. Only later, when I pursued history formally, did I realise they were history that have been forgotten, but not abandoned.”

The accounts shared by tribal elders, he says, were history in their own right. After completing his doctorate and taking up teaching, Chandrasekar began systematically preserving these oral traditions. So far, he has compiled more than 1,500 folktales and studied over 95 hero stones, apart from numerous rock art sites, petroglyphs and megalithic structures from across the region.

Speaking about tribal cultures, Chandrasekar believes modern society has much to learn from indigenous communities. “Even today, I find tribal communities more advanced than the modern world in many ways. European societies continue to struggle with backlash over sex education, but many tribal communities have been imparting it for centuries, integrating it naturally into their culture,” he said.

He points to a tribe in Dharmapuri where elders preserve songs sung on the eve of a wedding. “These songs speak about healthy sexual practices, mutual respect, and the responsibilities of marriage. Many tribal societies are matriarchal, which means there is genuine women’s empowerment. There is so much we can learn from them and adapt to contemporary life,” he said.

For Chandrasekar, folklore represents the true history of indigenous people. “Their traditions are carried through folklore, with elders educating the next generation. Preserving these cultures, especially those without written forms or visual depictions, is even more important than interpreting symbols etched in stone,” he said.

“I don’t know how many languages have already been lost in my lifetime, but I cannot stand by and watch another language or culture disappear when it can still be recorded.”

To expand this work, Chandrasekar established the non-profit Thonmam Varalatru Ayivu Arakkattalai, a trust dedicated to research and empowerment of tribal communities. “This task is far too vast for one person. So I began the trust and brought my students into the work. We conduct research across India, studying tribal cultures and documenting historical artefacts and ancient structures,” he said.

The trust functions independently, he emphasised. “We have never sought funds or favours. At most, we ask for shelter when we are in the field, and even then we take care of our own food. I fully sponsor my students from my salary.” Several of his students, he noted, have gone on to specialise in Subaltern Studies, which seeks to rewrite South Asian history from the perspective of marginalised communities.

“It was through these students and through All India Radio that we compiled over 1,500 folktales in Hindi and English. We are now recreating them in Tamil as well,” he added.

Looking ahead, Chandrasekar hopes to build a comprehensive digital archive. “We want to create a freely accessible database where all our findings will be uploaded. From medicinal knowledge to cultural practices and folklore songs, the aim is to enable further research,” he said.

E Seenan (36), a PhD scholar from Gopichettipalayam and a member of the trust, said his fieldwork has been transformative. “Attending a wedding ceremony of the Toda community in Ooty was one of the most enlightening experiences. I am now preparing my thesis on their culture,” he said.

Another member, C Elandhiryan, said the trust has documented tribes across TN for nearly two decades. “We are not confined to ancient history. We also document recent histories,” he said, adding that the group has already published one book and is working on a second on freedom fighters.

Each story preserved and each stone mapped is a stand against forgetting. For Chandrasekar, history lives not just in archives, but in people and the land they inhabit, and the work remains unfinished as long as voices go unheard.

(Edited by Dinesh Jefferson E)