Seated in a dark room lit by a single candle, Ishar Das Arora (the character is voiced by Indian actor Adil Hussain), an Indian Hindu who migrated from Pakistan to India and Iqbal-ud-din Ahmed (the voice behind this character is Pakistani actor Salman Shahid), a Pakistani Muslim who made the opposite journey, discuss memories from the 1947 Partition of India and Pakistan while playing a board game.

"God was a little late that day," Ishar comments, as he recounts the chaotic mass migration after the Partition. This scene from Child of Empire (CoE) is haunting.

Memories of the Partition are revisited in CoE, a 17-minute-long animated virtual reality (VR) docu-drama 'experience' - Sparsh Ahuja (23) from Malviya Nagar, who is the co-director, says, "Film is not the best way to describe CoE. It is an experience" - that was screened at the 2022 Sundance Film Festival.

Real-life inspirations

CoE has been created using Virtual Reality (VR) by Project Dastaan, a peace-building initiative, which was co-founded by Sparsh and Sam Dalrymple in 2018. Project Dastaan seeks to reconnect individuals who were displaced from their ancestral land during the 1947 Partition.

Over the course of this Project, the team conducted 30 interviews with individuals who had personally experienced the trauma of the Partition. Three selected interviews have served as inspirations behind two characters we 'meet' in CoE.

Ishar's character has been scripted keeping in mind the experiences of Sparsh's maternal grandfather, Ishar Das Arora and his paternal grandfather Jagdish Chandra Ahuja - both Ishar and Jagdish migrated from villages in the Punjab province of Pakistan (Ishar from Attock Tehsil and Jagdish from Dera Ghazi Khan), and settled in Tilak Nagar, New Delhi. Iqbal's character is inspired by Iqbal-ud-din Ahmad’s migration journey from Ropar (East Punjab) to Lahore.

"The idea was to give a sense of state narratives in the conversations with one another. Iqbal’s story represents the general Pakistani sentiment of how the Partition happened and Ishar’s story represents the Indian narrative," shares Dalrymple (25), co-producer. "The two stories complemented each other well," adds Omi Zola Gupta (25), screenwriter.

Treated with empathy

History books have recorded the impact of the Partition and the bloodshed that unfolded during the time. Critics often mention how Bollywood films tend to overdramatise these moments.

The creators of CoE make it a point to steer away from the conventional treatment and avoid sensationalising the violence. "When my nani and nana (maternal grandparents) talk about the Partition, it might be suppressed trauma, but there is nonchalance to it," shares Gupta.

The same sentiment is projected into the film as well. "By and large, when you speak to grandparents about the Partition, something that history told us to be a very traumatic event, they speak of it in a very casual manner, sometimes with a sense of humour as well," Gupta adds.

A unique aspect is how the film revisits Partition through the lens of childhood - almost every scene has a child in it. "We were trying to move it beyond politics, giving people the lens through which they can have greater empathy," mentions Gupta.

"When we started the project, the opening idea was to look at conflict from the lens of a child who wants to go home. All 30 people we spoke to were children when the Partition happened; they had no idea of what or why it was," adds Dalrymple.

Alternative filmmaking

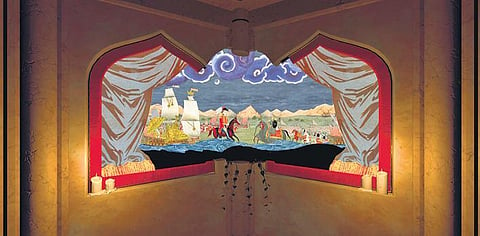

The VR experience is central to the film and helps transport the viewer amid the gruesome tragedy. Smoky skies, ground covered with blood, dilapidated establishments; it seems like 17 minutes of time travel.

"It takes away all sense of surroundings. It is a very powerful experience. When we were designing the film, it was less thinking about scenes and shots, as you would do in a conventional film. It was all about what world could we create," shares Sparsh.

Even though VR has been around for a while now, it is still inaccessible given the prerequisite of a specialised headset and additional gadgets. Commenting on the same, Sparsh adds, "I don't think it [VR] will replace traditional film. Not everyone has a headset. It depends on how the industry evolves in the next four to five years and the scale of adoption. With every film, you want as many people as possible to see it. But if people don't have access to the technology, then the industry can’t move forward. So it would be a shame if that didn’t happen."

The team is currently in process of creating another three-part animated project titled Lost Migrations. It is centred on lesser-known tales from the Partition, specifically highlighting the experience of women and the Indian diaspora.