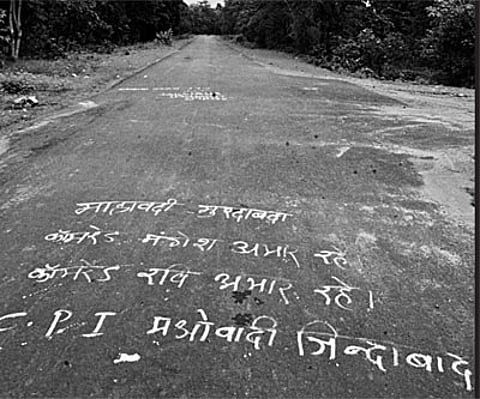

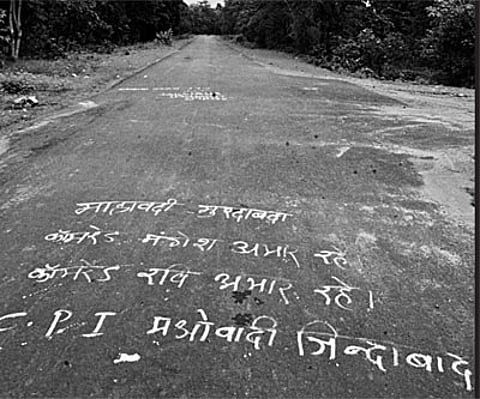

The closer one gets to the eastern border of the Gadchiroli district in Maharashtra, the closer one gets to Chhattisgarh and the eerily similar narratives of violence and counter-violence. Maoist graffiti marks the asphalt and the walls, while police outposts find themselves marooned in the middle of nowhere. The stories of brutal suppression, encounters and informant killings, and the accompanying threat of violence gets louder and louder.

“Nobody can even move anywhere. It’s too much of a risk,” says Veeresh Prabhu, the Superintendent of Police. He’s referring to the policemen posted at Laheri and Bhamragad police stations, which are closest to the Maoist “liberated-zone” of Abhujmarh in Bastar.

This has led to a presence of security personnel in the region, not something that has translated into security for the people.

“I asked them why they were beating my son, and they beat me as well,” says Dama Pada of Mungner. “They said I was feeding the Naxalites, and they beat me,” says Mungner’s village head.

A civil rights activist speaks of an incident of rape allegedly committed by a member of Maharashtra’s elite C-60 group. The victim was 13 years old. “She wanted to pursue the matter, but we believe that the family was too afraid,” the activist says.

The most damning words, however, come from a servant of the state, Gadchiroli’s deputy collector, Rajendra Kanfade: “The people are more afraid of the police than of the Naxalites.”

The Story of Mungner

On August 31, four villagers were beaten by the security forces during a routine operation in the predominantly Madia Gond village of Mungner in Gadchiroli.

“They came from all sides, and they asked all the villagers, men, women and children to come to one spot,” said Tukaram Walko, the village-head or ‘Patel’. He had been caught returning from his fields with an empty steel box. “A policeman saw the empty box, and said I was feeding the Naxalites. He slapped me then and there.”

“Then they told us not to support the Naxalites, and threatened us,” said another villager. “He (Hingle, the CO) said that I can kill 10 of you just like this.”

Mungner is said to be approximately three kilometres from Chhattisgarh. Crops have failed for lack of rain for two consecutive years now. For every 180 homes here, there is only one patta. Contractors have defaulted on NREGS payments, and the Forest Department has been cutting bamboo for `1 for over 30 years.

Unsurprisingly, the villagers reveal that the Maoists do visit them. Three years ago, they had even killed the then village-head for being a mukhbir or informant. At the same time, the villagers revealed that it was a ‘surrendered’ Maoist who had brought the police to their village.

“Don’t tell them,” screamed a woman from inside a hut, when one asked about his/her identity and an animated discussion in Gondi broke out among the other villagers.

“There were bullets flying across our homes,” they recalled.

This was not the first time the police had come to Mungner. The village lies deep within the jungle but a dirt road connects it to the Dhanora Police Station.

On April 6, 2009, there was an encounter near the village, and three security personnel were killed. The police claim at least seven Maoists were also killed.

That day, the villagers heard gunfire that lasted till evening, and claimed that the gunfire had even gone over their roofs.

“Us din duniya bhar ki gadiyan gaon aa gaye the (all the world’s cars had come to our village that day),” said Budram Galme, the sarpanch of Mungner, referring to the police rescue party.

Yet irrespective of the proximity to the Maoist ambush, the villagers claimed no one was mistreated by the police in retaliation.

“Munna Thakur (commander of the C-60) was good to us,” said a villager, “whenever there was an incident of firing nearby, he used to tell us to stay away. And no one from our village was harassed.”

“He may have been something else with other villages, but he was okay with us.”

The legend and infamy of Munna Singh Thakur

Munna Singh Thakur is a name well-known even in Adivasi villages of Gadchiroli district. The commander of the elite C-60, a specialist counterinsurgency group, Munna Singh Thakur lost his older brother Lalbabu Singh to an encounter with the Maoists on July 8, 1988.

“He was shot 17 times, I still remember that day,” said Thakur, who was 18 at the time, “He was left alone to fight. The other policemen had all run away. And those policemen are still in the service.”

Munna Singh Thakur would then serve in anti-Naxal operations in Maharashtra for the next 20-odd years. There are many who believe that the C-60 under Munna Singh Thakur worked directly under the auspices of the Director General of Police (Anti-Naxal Operations) Pankaj Gupta. Munna Singh Thakur functioned out of the Pendri police station, and effectively had a free hand from around 2004.

The villages around would grow to fear him and his reputation, or in the particular case of Mungner, find him reasonable — making him a proponent of the carrot-and-stick approach of counterinsurgency.

Nevertheless, 2009 was a particularly brutal year for the police. There were three widely reported incidents where the security forces were ambushed, with deadly results. Fifteen police officials including a sub-inspector were killed on February 1 near Markegaon, 16 police officials, including five women personnel were killed on May 17, and 18 were killed near the Laheri police station on October 8 during assembly elections.

Munna Singh Thakur was the CO when his party was ambushed near Mungner where they only suffered three casualties. The casualities of 2009 ensured that no police party can move within sensitive areas of Gadchiroli in smaller numbers.

In that year alone, there were a total of 52 fatalities from among the police, in contrast to a total of 27 fatalities among the police in the four years preceding 2009. In 2009, Gadchiroli district was elevated to being one of the worst-affected LWE (left-wing extremism) districts.

In 2010, there have been minimal incidents of violence, with only two fatalities among the police as of September 13. Interestingly Munna Singh Thakur, Pankaj Gupta and the then SP Rajesh Pradhan, were transferred out in 2009.

“The police had not followed standard operating procedures in 2009, they kept going out in small numbers and made mistakes. The incidents were self-created,” according to a local journalist in Gadchiroli, “Munna Thakur with his signature of carrying two rifles, was useful, quite dynamic, if he was told to rescue one police party, even when engaged in another area.”

“A particular incident took place where a police party was stranded in the jungle, and their commanding officer was too circumspect to move, believing they’d be ambushed if they did. Munna Thakur, was sent to rescue the party. And yes, the mission was accomplished with no casualties.”

“There were many incidents like that where I was involved,” said Munna Singh Thakur, now posted in Nagpur. “I once had to rescue a jawaan at midnight. He had lost one of his hands.”

“But I got tired of all of it,” he continued. “I had to take note of my family, my children are older now and the risks I took affected them. I have been wounded, my jawaans were killed. I got tired.”

The village of Paverval

Advocate Anil Kale, of the Indian Association of Peoples Lawyers

received a message through the Jailer of the Chandrapur jail, sent by one of his clients in prison.

The message regarded a young girl who had just arrived in prison. The child not even in her teens yet, having been born on March 20, 1996. In violation of the Juvenile Justice Act, she had been sent to prison after being arrested by the police in the village of Paverval on March 4, 2009, just two weeks short of her 13th birthday.

“My client had also told me that the girl claimed she was raped by the police,” said Kale.

The girl would eventually be released on bail after she was produced before the Juvenile Justice Board. She had been booked under sections 307 (attempt to murder), 143, 147, 148, 149 of IPC and Section 3, 25 of the Arms Act.

Payal (name changed) had been visiting her sister who lived Paverval when the police had raided the village on March 4, 2009.

An unidentified man had run past her sister’s house at the edge of the village as the police gave chase. Gunshots were heard, and the police returned to the house without the man. They started beat ing the villagers there, including Payal’s brother-in-law Kaju Potawe, insinuating they had been helping the ‘Naxalites.’

The police would go on to spend the night in Paverval village, with eight villagers, including Payal, detained in the home of Dayaram Jangi. The next morning, all of them were flown out by helicopter. At some point of that morning, Payal was raped repeatedly. One of her alleged rapists was none other than Munna Singh Thakur.

“She gave us graphic details, these were not things a 13-year-old would know,” said a civil rights activist from the Committee Against Violence on Women who was involved in the fact-finding team that would later take Payal to the police to register her complaint.

According to the fact-finding report Payal did not use the word rape. Instead “She used the phrase badmash kaam. Payal said that her breasts and her entire body were pressed. Then, that a portion of the male body from which urine is passed was pushed into that part of her body from which she urinates,” the report says.

“The first person who raped her told her that he was Munna Singh Thakur, and that she must have heard of him. Payal said that she was in great pain, and after some time she fainted. She gained consciousness when the police were splashing water on her,” it adds.

Kale said the investigation into the rape was initially lukewarm. “We even took the girl and her family to meet the Superintendent of Police, but he stuck by his men. Eventually, an inquiry took place and he was transferred,” he said

“At night, the DSP had asked us about where we’d all be sleeping. They knew we’d be sleeping at the guesthouse. And over there, the girl identified Munna Thakur, loitering around the guest house.”

Munna Singh Thakur refutes all the allegations. “All those allegations are just the work of Naxals,” he said. “There were 60-70 of us there, and we encountered that girl, and put her on a helicopter and took her with us. Nothing else.”

But that is not the only cause of anger against Munna Singh Thakur. “Munna Singh Thakur should be hanged,” says Manik Jangi of Paverval village. His own son Ramse Jangi was shot dead by a police-party lead by Munna Singh Thakur in 2006. Another son is the only in the village to have studied past Class 11.

— javed@expressbuzz.com

The red infection rages unabated in newer places

Five security personnel were killed on August 31, 2010 in Kanker district in Chhattisgarh. Two days later, in the neighbouring district of Gadchiroli in Maharashtra, security personnel are on a patrol on Dhanora road.

Anti-landmine vehicles, and groups of 4-5 CRPF personnel and state police are positioned 30-40 metres along the Gadchiroli-Dhanora road. Just a few kilometres through the jungle is Kanker, where search operations are taking place.

“Gadchiroli is Bastar” isn’t something that far-fetched and few disagree with it.

Gadchiroli borders Rajnangoan, Bijapur, Narainpur and Kanker districts of Chhattisgarh and, more specifically, Abhujmarh, the infamous Maoist bastion.

The river Indravati forms the border through Bijapur and Gadchiroli, yet the districts and their forests intersect near Bhamragad or Laheri police station in the north, and it is no surprise that here the police live in virtual prisons.

Nearby, three young men cross the Indravati in a dugout boat from Chhattisgarh to enter Gadchiroli. There is a clear organic link between Bastar and Gadchiroli. The Madia Gonds of Gadchiroli are similar, yet differ from the Murias and Koyas of Bastar, often referring to the ‘Abhuj Murias’ or ‘Hill people’ of Abhujmarh as the ‘Bada Gonds’.

“Did the Salwa Judum ever come to your village?” I asked one of the boys who just came from Bastar. He is a Muria boy. He affirms that the Salwa Judum had come to his village. And they burnt their village down, and beat people. Yet then a forest department ward officer shows up. The boy says hello to him and leaves.

Where the police evoke more terror than the rebels

Late August, a team of government representatives crossed the Indravati. They were led by the Deputy Collector, Rajendra Kanfade, and they crossed into Abhujmarh after being detained by the police in Laheri, who refused to provide them protection.

They had gone into Naxalite territory on August 24, a Tuesday, to check on the condition of the Ashram schools in the village of Binagonda. There was no news of them for the next 18 hours, and many officials believed they had been kidnapped by the Maoists. Yet they returned the following evening, unscathed — nobody had harassed them. Kanfade would then deliver a scathing report about the condition of the schools in Binagonda.

“The situation of these schools is terrible, there are irregularities in the number of students and malnutrition is pervasive,” the report says.

“We already have schools from the Zilla Parishad, why do we need schools from the Tribal Welfare department also?” he asked.

“Some people are taking advantage of poverty. This is all just a money-making racket.”

There were around a hundred or more villagers who had come to meet the deputy collector, the tehsildar and other members of the team at Binagonda and the officials took cognisance of the relationship the people had with the Naxalites as well.

“They (the Naxalites) come to these villages with guns. So the villagers do what they want. And here, they’re even paying for food,” Kanfade continued, “I have been to many areas, and here too, it seems that the people in these areas are far more afraid of the police than of the Maoists.”

“There is legalised violence committed by the state, and illegal violence committed by the Maoists. I do not agree with the violence of any party, especially the Maoists, but I personally feel that the legalised violence of the state is far more destructive.”