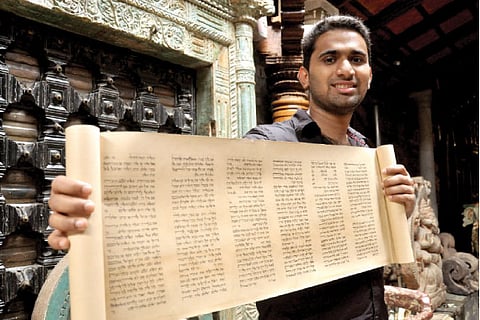

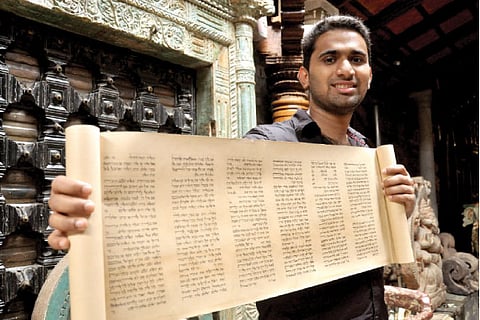

For Thoufeek Zakriya (24), the written word knows no religion. The Muslim calligrapher’s fascination with the Hebrew script took on a new dimension following a meeting with his friend and Kannur resident Srinath at Fort Kochi in 2009. Zakriya had told Srinath about his interest in calligraphy and Jewish history, and he took along the Birkat Ha Bayit, the Jewish blessing for the home, to show his friend. The words went like this:

Let no sadness come through this gate.

Let no trouble come to this dwelling.

Let no fear come through this door.

Let no conflict be in this place.

Let this home be filled with the blessing of joy and peace.

Srinath was impressed. Their shared interest in Jewish culture took the friends to Jew Town, Kochi. While there, the duo saw an old woman sitting outside her house, stitching a kippah (a skull cap). At the insistence of Srinath, Zakriya showed his Hebrew calligraphy to her. “When she saw it, she became very excited,” says Zakriya. “That was Sarah Cohen. She asked me how I had learnt the art. I said I was self-taught.”

Cohen then invited them into her house, and there began a life-long friendship. “She is like a grandmother to me,” says Zakriya, who is a management trainee at a Taj hotel in Bangalore.

Apart from Hebrew, Zakriya is an expert in Samarian, Syrian, English, Sanskrit, Hindi and Aramic calligraphy.

“The printing of an alphabet has evolved from the calligraphic script,” says Zakriya. But to do the art well, you need to have an idea of the language. “Since Arabic is the base for all Semitic languages, it was easy to learn. I know a little bit of Arabic,” says Zakriya. The Semitic languages start from right to left. The first alphabet for all the languages is the Aleph.

The Syrian script is one of his favourites. A few years ago, Zakriya went to the office of a Syrian Christian spice merchant. While there, he saw a picture of a cross placed against a floral background with a Syrian script underneath. “The merchant did not know how to read the language,” says Zakriya.

Thereafter, Zakriya, who was intrigued by the Syrian calligraphy, designed a similar one, based on the first verse in the Bible: ‘In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth’.

Incidentally, the equipment to make these eye-catching words is simple: a bamboo reed, to be used as a stylus, a Lamy calligraphic pen, which costs `1,500, and Indian ink.

Happy with his art, the otherwise reserved Jews of Fort Kochi embraced Zakriya into their fold. “One day, Cohen took my parents, sisters and me for a visit to the Jewish synagogue on the festival day of Simchat Torah (a celebration marking the conclusion of the cycle of public readings of the Torah),” says Zakriya. “This is a rare honour for a Muslim family.”

Along the way, Zakriya also gained international attention. “Zakriya has made many calligraphic representations of the Torah by using the ancient Kufic Arabic script,” says Paul Rockover in an article in Huffington Post. “Such work is a rarity in the calligraphic world, and his innovation has brought Zakriya accolades from all over the world.” In fact, Zakriya has been commissioned by Jews from as far away as Ukraine and US to create works that combine Arabic calligraphy with Jewish prayers. “Some people saw the different exhibits on my blog, got interested, and contacted me,” says Zakriya.

Today, Zakriya is regarded as the only Muslim Hebrew calligrapher in south Asia. “His work reminds us of the shared cultural and religious heritage of Jews and Muslims,” says Dr Navras Jaat Aafreedi, assistant professor, Department of History and Civilisation, Gautam Buddha University, who has done extensive research on Indian Jews. “It will help overcome disputes, conflicts and differences between the two groups.” In fact, while presenting a paper at a conference at the University of Sydney in February, Aafreedi spoke at length on Zakriya’s calligraphy.

Zakriya “accidentally” discovered the art form. When he was a teenager, he brought a pen on which there were symbols in English done in the calligraphic style. “I decided to copy them and that was how my interest in calligraphy began,” he says. Brought up on the island of Mattancherry, near Kochi, he spent hours doing calligraphy. “It has become a passion and an obsession,” he says today.