Hamid’s mother submitted a mercy plea to Pak PM Nawaz Sharif requesting him to pardon her son for travelling to that country without valid papers. Till date, Hamid hasn’t been given consular access nor allowed to talk with his family.

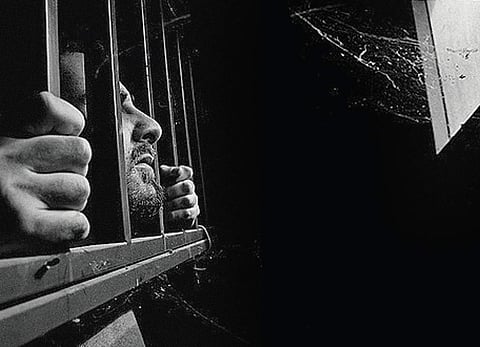

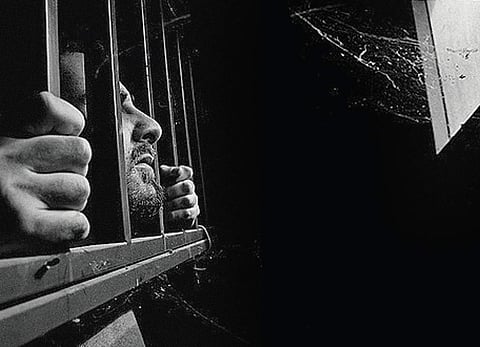

When Pakistan released 447 Indian prisoners on Christmas last year, a distraught mother had lined up at the Wagah-Attari border hoping to see her son return. But that did not happen. Fauzia Ansari’s son Hamid Nehal Ansari continues to languish in a Pakistani jail for the last four years. Like hundreds of others who are behind the bars in the neighbouring country, there’s no word on Hamid too. The ordeal started four years ago. Hamid, a 32-year-old engineer from Mumbai, was always keen to promote education in Afghanistan and Pakistan with his Rotary friends. He arrived in Kabul on a visit visa for a job interview on November 4, 2012. Eight days later on November 12, he crossed over to Pakistan from Afghanistan through the Torkham

Pass allegedly without a visa. On November 14, he was picked up from a hotel in Kohat. (Kohat is a city in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. It is the capital of the Kohat district. The town centres on a British-era fort, various bazaars and a military cantonment).

But questions are being raised why would a person who has been to Pakistan before and who knows what it means to be an Indian on Pakistani soil take such a risk?

The reason: Hamid was in love with a girl in Kohat who was given away in marriage under a jirga ruling to settle a tribal feud called vani. He decided to help her and chalked a rescue plan with his Pakistani online contacts. “The girl sought Hamid’s help. My son wanted to rescue her by taking the help of his friends in Pakistan,” Fauzia says.

The names of Hamid’s Pakistani online friends are known and conversations with them are on record along with the statements of the police officers who picked him up from the hotel. Attempts to register an FIR of his arrest and detention failed till the Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances (CIED) ordered the registration of one in 2014. At the same time, a habeas corpus petition was moved in the Peshawar High Court.

“At the time of his arrest, the only charge against him was that he had illegally entered Pakistan. The maximum punishment for that is six months. But Hamid’s detention has already exceeded four years. If the police had found a missile or a couple of IEDs in his travel bag, he might have been booked for espionage, sabotage and terrorism. But there is no evidence of Hamid being accused of any such offence, or any offence at all,” says IA Rehman, secretary general, Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP).

“The authorities denied of having any knowledge of him for a long time. Finally, they disclosed that he was tried by a military court and sentenced to three years’ imprisonment,” Rehman adds.

Hamid’s mother even submitted a mercy plea to Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif requesting him to pardon him for travelling to Pakistan without proper documents. Till date, Hamid hasn’t been given consular access nor allowed to talk with his family in Mumbai. There have been concerns about threats to his life in prison after he was attacked thrice by fellow inmates. “The government must ensure his safety and it will be proper to start preparing for his repatriation to India,” Rehman says.

The Indian Ministry of External Affairs in a press statement has asked Pakistan to grant consular access to Hamid and Kulbhushan Yadav. Pakistan had arrested Yadav from Balochistan in March 2016 and accused him of being an Indian Navy officer who was deputed to the intelligence agency, Research and Analysis Wing (RAW).

Yadav has been accused by Pakistan of planning “subversive activities” in the country as a RAW agent. India has acknowledged that Yadav had served in the Navy but denied that he has any connection with the government now. Pakistan has so far turned down India’s request for consular access to Yadav.

In accordance with the provisions of the Agreement on Consular Access 2008, both India and Pakistan are required to exchange lists of prisoners in each other’s custody on January 1 and July 1 every year.

According to the exchanged list of prisoners by Pakistan on January 1, there are about 43 Indian prisoners in Pakistan and 25 Pakistani prisoners in India. The earlier list (July 2016) showed 518 Indian prisoners, including 463 fishermen, in Pakistan’s jails.

The figures received by the Pakistan Interior Ministry since 2016 through the Foreign Office from Pakistani High Commission in New Delhi reveal that Pakistani prisoners are languishing in eight Indian jails out of 1,387 across the country. It is unclear if other jails have Pakistani prisoners or not.

One such prisoner is Rubina Akhtar, a young Pakistani woman detained in a Jammu jail since 2012 along with her four-year-old daughter. According to reports in Pakistan media, she had apparently been arrested after she was abandoned in New Delhi by her husband while she was travelling for medical treatment, and left without any money or documents. Though her jail term ended in 2013, it has not been possible for her to return home because the Pakistan Interior Ministry has not confirmed her nationality.

But according to her interrogation report, Rubina has been in jail since November 6, 2012, along with her minor daughter. She was arrested at Kanachak in Jammu after she crossed the border inadvertently and did not know the way home. The Jammu and Kashmir High Court in a verdict has asked the state and Central governments to expedite the confirmation of residential address of Rubina.

Fishermen are often freed on special days only to be caught again. Pakistan released 447 of them on December 25, 2016, and caught another 65 on December 28. The problem is with other prisoners who are not released even after they have served their sentence.

Linked to Hamid’s case is another story of tragic disappearance. On August 19, 2015, Zeenat Shahzadi, a 24-year-old journalist, was on her way to work in Lahore in an autorickshaw when she was abducted by armed men. HRCP believes she was taken away by security forces.

In August 2013, Zeenat had secured the special power of attorney from Fauzia and pursued his case in the Peshawar High Court and at CIED. She was to appear before the commission on August 24, 2015, but was picked up from a bus stand near her house in Lahore on August 19. Earlier in the same month, she was held by the police for a short while after she met the Indian high commissioner at a public event.

“Zeenat was the first woman journalist suspected to have been subjected to enforced disappearance in Pakistan. Her case highlights how this cruel practice is being used against people, even as hundreds of cases of disappearances remain unresolved,” says Champa Patel, Amnesty International’s South Asia Director.

According to CIED–which is investigating Zeenat’s case–1,401 of 3,000 cases are still pending. The number of disappearances is increasing every year with the commission saying 728 people were added to the list last year, the highest in any year since its inception. Most of them were taken away from Balochistan. In 2015, there were 649 cases.

“In Pakistan, journalists face serious threats to their freedom of expression and physical safety from armed groups and security forces. The government’s duty is to protect journalists and punish those responsible for violating their rights,” Patel said.

Zeenat’s disappearance has taken a toll on her family. In March 2016, her teenage brother Saddam committed suicide as he was unable to cope with the loss

of his sister.

“Pakistan should sign and ratify without reservations the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances. If the country wishes to be seen as a modern, rights-respecting nation, then it should break with its ugly history of enforced disappearances and make the safe recovery of thousands of people still unaccounted for,” Patel adds.

Hamid Nehal Ansari

Engineer from Mumbai

Has been languising in a Pakistani jail for the last four years

Keen to promote education in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Hamid arrived in Kabul

on a visit visa for a job interview on November 4, 2012. Eight days later, he crossed over to Pakistan from Afghanistan allagedly without valid documents. On November 14, he was picked up from his hotel in Kohat.

Kulbhushan Yadav

Indian citizen arrested in Balochistan

Pakistan says he’s an Research and Analysis Wing agent

Although India recognises Yadav as a former naval officer, it however denies his links with the government now, and maintains that he took early retirement and was possibly abducted from Iran

according to pakistan’s commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances, 1,401 of 3,000 cases are pending. The numbers of disappearances are increasing with the commission saying 728 people were added to the list last year, highest in any year since its inception

Pass allegedly without a visa. On November 14, he was picked up from a hotel in Kohat. (Kohat is a city in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. It is the capital of the Kohat district. The town centres on a British-era fort, various bazaars and a military cantonment).

But questions are being raised why would a person who has been to Pakistan before and who knows what it means to be an Indian on Pakistani soil take such a risk?

The reason: Hamid was in love with a girl in Kohat who was given away in marriage under a jirga ruling to settle a tribal feud called vani. He decided to help her and chalked a rescue plan with his Pakistani online contacts. “The girl sought Hamid’s help. My son wanted to rescue her by taking the help of his friends in Pakistan,” Fauzia says.

The names of Hamid’s Pakistani online friends are known and conversations with them are on record along with the statements of the police officers who picked him up from the hotel. Attempts to register an FIR of his arrest and detention failed till the Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances (CIED) ordered the registration of one in 2014. At the same time, a habeas corpus petition was moved in the Peshawar High Court.

“At the time of his arrest, the only charge against him was that he had illegally entered Pakistan. The maximum punishment for that is six months. But Hamid’s detention has already exceeded four years. If the police had found a missile or a couple of IEDs in his travel bag, he might have been booked for espionage, sabotage and terrorism. But there is no evidence of Hamid being accused of any such offence, or any offence at all,” says IA Rehman, secretary general, Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP).

“The authorities denied of having any knowledge of him for a long time. Finally, they disclosed that he was tried by a military court and sentenced to three years’ imprisonment,” Rehman adds.

Hamid’s mother even submitted a mercy plea to Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif requesting him to pardon him for travelling to Pakistan without proper documents. Till date, Hamid hasn’t been given consular access nor allowed to talk with his family in Mumbai. There have been concerns about threats to his life in prison after he was attacked thrice by fellow inmates.

“The government must ensure his safety and it will be proper to start preparing for his repatriation to India,” Rehman says.

The Indian Ministry of External Affairs in a press statement has asked Pakistan to grant consular access to Hamid and Kulbhushan Yadav. Pakistan had arrested Yadav from Balochistan in March 2016 and accused him of being an Indian Navy officer who was deputed to the intelligence agency, Research and Analysis Wing (RAW).

Yadav has been accused by Pakistan of planning “subversive activities” in the country as a RAW agent. India has acknowledged that Yadav had served in the Navy but denied that he has any connection with the government now. Pakistan has so far turned down India’s request for consular access to Yadav.

In accordance with the provisions of the Agreement on Consular Access 2008, both India and Pakistan are required to exchange lists of prisoners in each other’s custody on January 1 and July 1 every year.

According to the exchanged list of prisoners by Pakistan on January 1, there are about 43 Indian prisoners in Pakistan and 25 Pakistani prisoners in India. The earlier list (July 2016) showed 518 Indian prisoners, including 463 fishermen, in Pakistan’s jails.

The figures received by the Pakistan Interior Ministry since 2016 through the Foreign Office from Pakistani High Commission in New Delhi reveal that Pakistani prisoners are languishing in eight Indian jails out of 1,387 across the country. It is unclear if other jails have Pakistani prisoners or not.

One such prisoner is Rubina Akhtar, a young Pakistani woman detained in a Jammu jail since 2012 along with her four-year-old daughter. According to reports in Pakistan media, she had apparently been arrested after she was abandoned in New Delhi by her husband while she was travelling for medical treatment, and left without any money or documents. Though her jail term ended in 2013, it has not been possible for her to return home because the Pakistan Interior Ministry has not confirmed her nationality.

But according to her interrogation report, Rubina has been in jail since November 6, 2012, along with her minor daughter. She was arrested at Kanachak in Jammu after she crossed the border inadvertently and did not know the way home. The Jammu and Kashmir High Court in a verdict has asked the state and Central governments to expedite the confirmation of residential address of Rubina.

Fishermen are often freed on special days only to be caught again.

Pakistan released 447 of them on December 25, 2016, and caught another 65 on December 28. The problem is with other prisoners who are not released even after they have served their sentence.

Linked to Hamid’s case is another story of tragic disappearance. On August 19, 2015, Zeenat Shahzadi, a 24-year-old journalist, was on her way to work in Lahore in an autorickshaw when she was abducted by armed men. HRCP believes she was taken away by security forces.

In August 2013, Zeenat had secured the special power of attorney from Fauzia and pursued his case in the Peshawar High Court and at CIED. She was to appear before the commission on August 24, 2015, but was picked up from a bus stand near her house in Lahore on August 19. Earlier in the same month, she was held by the police for a short while after she met the Indian high commissioner at a public event.

“Zeenat was the first woman journalist suspected to have been subjected to enforced disappearance in Pakistan. Her case highlights how this cruel practice is being used against people, even as hundreds of cases of disappearances remain unresolved,” says Champa Patel, Amnesty International’s South Asia Director.

According to CIED–which is investigating Zeenat’s case–1,401 of 3,000 cases are still pending. The number of disappearances is increasing every year with the commission saying 728 people were added to the list last year, the highest in any year since its inception. Most of them were taken away from Balochistan. In 2015, there were 649 cases.

“In Pakistan, journalists face serious threats to their freedom of expression and physical safety from armed groups and security forces. The government’s duty is to protect journalists and punish those responsible for violating their rights,” Patel said.

Zeenat’s disappearance has taken a toll on her family. In March 2016, her teenage brother Saddam committed suicide as he was unable to cope with the loss

of his sister.

“Pakistan should sign and ratify without reservations the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances. If the country wishes to be seen as a modern, rights-respecting nation, then it should break with its ugly history of enforced disappearances and make the safe recovery of thousands of people still unaccounted for,” Patel adds.

Zeenat Shahzadi

Journalist

Had taken up Hamid Ansari’s case before being picked up by gunmen

On August 19, 2015, Zeenat Shahzadi, 24, was on her way to work in Lahore in an autorickshaw when she was abducted by armed men. Pakistan’s HRCP believes

she was taken away by security forces.

Rubina Akhtar

Pakistan citizen and mother of 4-year-old girl

She could not be sent home since Pakistan has not confirmed her nationality

Rubina has been in a Jammu jail since November 6, 2012 along with her daughter. She was arrested at Kanachak after she crossed the border inadvertently