When Oscar Wilde said, ‘All art is immortal’, he was probably thinking of bone carvers. For, quite literally, they render animal bones immortal by transforming them into artefacts. Ironically, the tradition, which dates back to pre-historic times, has been under a fading spell over the last few decades. The lack of patrons, scarcity of materials and legal restraints have pushed many practitioners away from the craft. Only a handful of artisans, in Uttar Pradesh’s Lucknow and Barabanki, continue to take it forward. Jalaluddin Akhtar is one of them.

The National Award-winning artisan, who recently showcased at an exhibition of local handicrafts at the Central Command of the Indian Army, Lucknow Cantonment, joined the family profession in 1980.

“I have been practising the craft since. I learnt it from my maternal uncle, and it has been in the family

for over 50 years, across three generations,” says Akhtar, who is slowly handing over the reins to his 29-year-old son, Aqeel.

Artisans such as the Akhtars have been carving bones to create intricate artworks for centuries. Born out of the necessity to create hunting tools, bone carving soon transformed into a form of art, adorning the royal courts of the Mughals, as well as finding a special place among the Nawabs. It is said to have been practised in India since the 16th century when royals would commission works in ivory. But when the tusk trade was banned in the 1990s, using buffalo bones emerged as a legal and cheaper alternative.

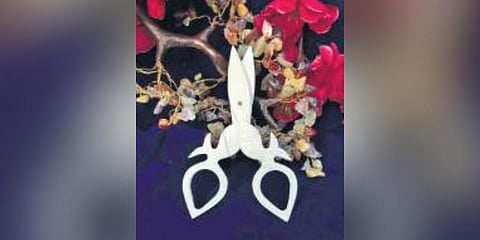

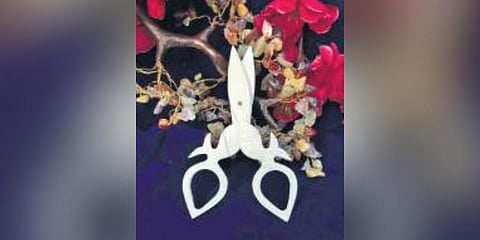

The artefacts are known for their impressive marble-like finish. One of their most attractive features is the well-crafted jaali (lattice) work with bel-patti (floral vines). “While elements of Mughal architecture inspire most designs, to keep up with modern tastes, we have started incorporating newer forms of geometrical patterns,” says 55-year-old Jalaluddin. The Akhtars create products across three categories: jewellery, home décor and office accessories. So there are alluring lamps, handy knives and organisers, wall hangings, dainty earrings, necklaces and more. “There’s no end to what you can create if one keeps improvising,” he adds.

The process begins with procuring bones from slaughterhouses. They are then cut into smaller pieces of different shapes, and straightened and shaved with an electric sander. After that, the pieces are boiled in soda for three hours to remove the fat from the bone surface.

Once dried, the piece, big or small, is designed using a drill and stencils. “The drill press has made the process more time-efficient. Earlier, the entire carving was done manually using the indigenous chausi (chisel),” Jalaluddin says. But that’s limited to the basic shapes; the elaborate carvings, particularly in

the centre, still have to be done by hand using needle files. Sometimes for minuscule designs that require precision and stability of surface, temporary specialised tools are also made by the artisans themselves. For instance, wooden logs are fixed on stone blocks in order to keep the bone canvas and the artisan’s hand in place while carving. Not surprising that the process involves exceptional hand-eye coordination, demanding utmost precision and sheer dexterity.

The edges of the smaller pieces are filed and glued together to form the larger parts of the artefacts, which are first cleaned using hydrogen peroxide, and then laid out in the sun to whiten. Each piece is polished with a buffing machine. All the bits are combined to give the product its ultimate shape. “The process takes around two days for smaller pieces like earrings or key chains, and as long as 35 days to finish larger ones such as lamps or storage boxes for jewellery or perfumes,” says Jalaluddin, adding that the excess fragments and left-over bone pieces are sold to recyclers, who use them in fertiliser industry.

To popularise the art form, his son Aqeel, who joined the family business 15 years ago, has started leveraging modern tools of social media marketing—eye-catching art pieces populate their Instagram account—and now sells their creations both offline and online. The latter also allows them to take international orders. Another effort taken by the Akhtars in the same direction is conducting workshops as part of the government’s initiatives, such as the USTTAD (Upgrading the Skills and Training in Traditional Arts Crafts for Development) and Guru Shishya Parampara Schemes.

When asked why he chose to stay back and revive the dying art of bone carving, instead of looking out for better opportunities like many of his peers, Aqeel says, “These traditions are valuable and cannot

be allowed to disappear. This is our legacy.”