A 1992 leaf plate from Nepal; photographs of tree huggers from the Chipko movement in the Himalayas, circa 1994; and a paper bag from Delhi, dated 2022. Separated by time and place, the three objects have traversed all boundaries to now find a spot next to each other at the newly opened South Asia gallery at UK’s Manchester Museum.

The seemingly random articles talk about the “traditions of care for the environment that are everyday customs in South Asian cultures”, says Nusrat Ahmed, who has curated the inaugural exhibition at the space.

“The Indian eating plate displayed in the gallery is made with dried leaves stitched together with tiny wooden sticks. Traditionally made by women, and often used for festivals and at temples, these plates are being used today as biodegradable alternatives to plastic,” she says, adding, “These stories needed to be told to inspire people.”

With this gallery, the Manchester Museum, last month, became the first such institution to have

a permanent space dedicated to the subcontinent in the country. The objective is to represent the diaspora from the region and preserve its history in museums, something that Ahmed acknowledges

was long over-due.

A first-generation British-born Pakistani, she remembers growing up feeling a void when it came to accessing her cultural heritage in public spaces in the UK. “I felt that I didn’t belong in museums,” she recalls, adding, “If I had the opportunity of seeing myself within such spaces, through the stories being told, then finding a way to connect to my heritage would have been far easier.”

So, for the exhibition, she teamed up with the South Asia Gallery Collective, comprising 30 co-curators —community leaders, educators, artists, historians, journalists and musicians—who have centred their storytelling and the development of the gallery around their own and their families’ experiences in both professional and personal spheres. They have lent tangible memories documenting their histories for the showcase. For instance, Fal Sarker, the grandson of physicist and mathematician Satyendra Nath Bose, who is best known for his work on quantum mechanics, has contributed a collection of letters exchanged between Bose and Albert Einstein. Another Collective member (name not revealed), a journalist, uses her grandmother’s saree passed during Partition to tell the larger story of migration and the shared histories of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. “This unique personalised approach humanises the gallery, telling stories about real people,” Ahmed says.

Unlike other museums that have exhibits usually categorised by time periods, the exhibition, featuring 140 historic artefacts, is divided into what Ahmed calls “anthologies”. The categories include ‘Past & Present’, ‘Lived Environments’, ‘Science & Innovation’, ‘Sound, Music & Dance’, ‘British Asian’, and ‘Movement & Empire’. The most important part, for her, while curating the show was to make sure “lots of voices are heard and equally represented”.

Which is why a significant part is also dedicated to stories of the LGBTQ+ community. Like the one that is put forth by social worker and another Collective member Kirit Patel, who has created a collage-of-sorts out of pamphlets, media clippings and other literature from the late 1990s about queer spaces in the UK, especially for people of colour, to document and encourage dialogue around experiences of coming out.

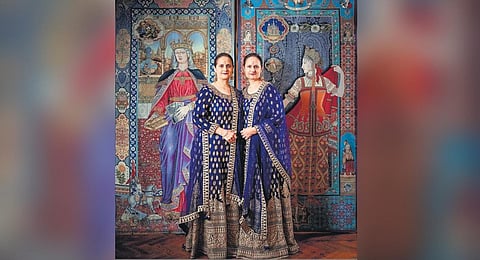

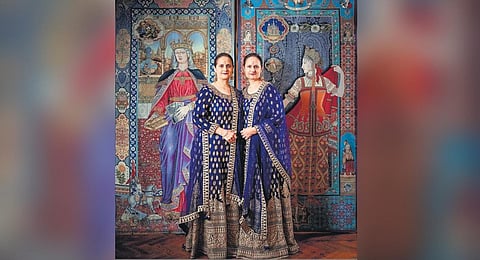

The most striking and completely unmissable exhibit, however, is an azure mural by two sisters—the Singh Twins (Amrit and Rabindra Kaur Singh)—that welcomes visitors right at the entrance. The 17-metre-long commissioned work, an “emotional map” of South Asia, features both British and Indian iconography that capture how the subcontinent’s experience transitioned from the ancient times to present-day, making its way through colonialism. In this shared history of an entire region, reflects the twins’ own identity and experience as artists of dual descent. “It explores interconnected and hidden histories, which challenge institutionalised prejudice, racial stereotyping and misperceptions about cultural identity and ownership,” Ahmed further elaborates.

Another installation that is symbolic of the juxtaposition of the South Asian and British identities of the diaspora is a cycle-rickshaw from Bangladesh that has been decorated by citizens of Manchester.

There is, however, only so much that a single exhibition can showcase about a region that has such a rich and diverse history. Which is why, Ahmed says, “the space will continue to evolve and we’ll continue to co-curate and collaborate with new people moving forward so that we can represent different cultures and countries”.