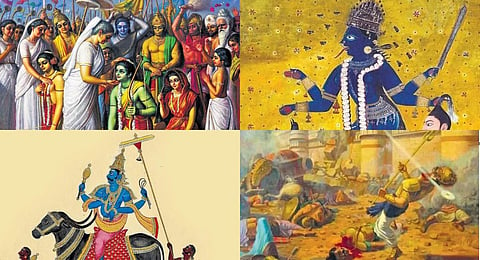

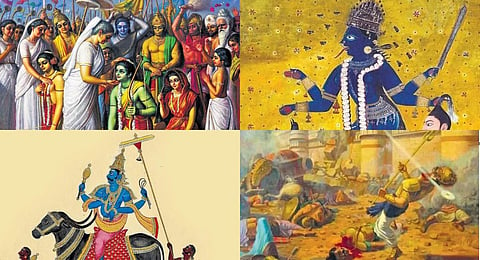

We ask four mythological writers to share their favourite Diwali stories.

The Wrath of Kali

by Koral Dasgupta

Diwali, particularly in northern India, is associated largely with the worship of Lakshmi, the goddess of prosperity. The eastern states, however, host Kali Puja on the day. While both Lakshmi and Kali are manifestations of Shakti, they are vastly dissimilar in their identity. The latter is a warrior, tasked to annihilate horrific demons. The reference is a metaphor for the inner evils of humans, like arrogance, jealousy, greed and rigidity.

Legend has it that two notorious demons, Shumbha and Nishumbha, were destroying the peace and stability of the cosmos. To battle them, Devi Durga transformed into the fierce Mahakali. With a complexion as dark as amavasya (moonless night), her nakedness symbolised her purity—she had nothing to hide and nothing could be hidden from her. A garland of skulls adorned her neck, signifying slayed vices. After a tremendous battle, the Devi eliminated the demons.

Once invoked, however, the energy of Mahakali was inexhaustible. She continued smashing everything that came in her way. To contain her vigour, Devadidev Shiva offered himself before the goddess. Kali stepped on his chest and calmed down immediately, sticking her tongue out in embarrassment. Alternative texts claim that Kali’s holy touch turned a shava (corpse) to Shiva.

Shiva, also called Kaal or Mahakaal, represents time, which puts everything in order. The myth shows Kali partnering with her consort, Kaal, to maintain the cycle of karma and eradicate evil. She reunites with him after restoring purity and peace on earth. The divine union is celebrated as Kali Puja. The idol stands over a sleeping Shiva, and hymns addressing the goddess as Mahamaya are chanted. Liberated from the evils, one no longer sees the furious Mahakali, but the motherly Mahamaya, who wears calm similar to Lakshmi.

Different stories from Indian mythology are thus interlinked. The underlying message of Diwali remains the victory of good over evil. Be it Kali in the east or Lakshmi in the north, both beliefs and practices are in harmony, inviting followers to take that eternal leap from darkness to light.

(Dasgupta is the author of the Sati Series, Rasia: The Dance of Desire and Power of a Common Man: Connecting with Consumers the SRK Way)

Notorious Narakasura

by Anuja Chandramouli

The story of how Narakasura, whose every pore supposedly oozed evil, was slain is a tale with a twist worthy of Hitchcock. Naraka was born at the end of Krita Yuga when Vishnu, in his Varaha (Boar) avatar, took out Hiranyaksha, another asura, whose shocking shenanigans sank Bhumi Devi to the bottom of the ocean. While Varaha bore her to the surface on his tusks, a single drop of sweat—the only sign of his mighty exertions—landed on her, impregnating the goddess.

Blessed with a boy, Bhumi Devi asked Varaha to grant him immortality. She was gently refused, but told that Naraka could only be slain by her. Breaking off his tusk, Varaha offered it to Naraka, urging him to stay true to dharma. The advice was disregarded and Naraka, armed with the promise of invincibility, began his reign of terror. His stronghold, Pragjyotishapura, was impregnably fortified and guarded by the deadly Mura. Naraka eventually went too far when he raided Indra’s capital, Amaravathi, and carried away 16,000 damsels, but not before snatching the earrings mother Aditi was wearing.

Krishna was asked to set him straight. The lord was with Satyabhama (queen consort), who had been complaining that he was always too busy for her. Playfully, grabbing her by the waist, he placed her on Garuda, and they took off on a date/perilous mission. Krishna made short work of Pragjyotishapura’s vaunted defences and slew Mura, earning himself the title of ‘Murari’.

Naraka used the tusk gifted by Varaha to strike Krishna in the chest. Seeing her husband drop in a dead swoon, Satyabhama realised her outing was ruined. Enraged, she picked up a bow and released an arrow, which mortally wounded Naraka. It was then that Krishna rose and allowed the truth to shine through. Naraka understood that Varaha’s weapon could not be used against an avatar of Vishnu, and that Satyabhama was an incarnation of Bhumi Devi. Prostating himself before his parents, he died peacefully having been cleansed of his sins, embracing dharma in his dying moments, thus fulfilling his purpose in the grand design of the universe and achieving moksha.

A tearful Bhumi Devi asks Krishna to ensure that Naraka’s memory be preserved for all of time, and his life and death celebrated with lights and sweets so that his legend may remind humanity to dispel the evil in their hearts. Krishna acceded to her request. True to his word, Diwali has since been celebrated as a reminder to continue the fight against demons within and without, knowing that damnation is always closer than salvation, but that is no reason to stop trying to be better.

(Chandramouli is the author of Arjuna: Saga of a Pandava Warrior Prince; Kamadeva: The God of Desire; Shakti: The Divine Feminine; and Abhimanyu: Son of Arjuna)

Kaikeyi’s Redemption

by Kavita Kane

In the Ramayana, Kaikeyi is a looming paradox: from a loving but ambitious mother to a hated wife, she is reduced to become the most reviled character in the epic—a symbol of female villainy in the collective cultural narrative. Diwali is the day Rama, the son she wronged, forgives her by bowing down to touch her feet in honour.

Kaikeyi is that doomed woman who plays the significant role of the archetypal wicked stepmother. Her goodness quickly dissolves to get myopically bracketed into extremes of black—the Devi becomes the she-devil. By being slotted into antipodes, Kaikeyi is turned into an oversimplified embodiment of evil. Remove this lens of prejudice, and you will see a person of conviction—strong and assertive in manner and measure.

If Rama’s magnanimity makes him virtuous, it also makes Kaikeyi vulnerable to several interpretations. One thread is that Rama saw her as his saviour and that of the entire family from a fate only she could help pave. Dashratha was an overprotective father who would not have allowed his beloved son to step out of the palace, so how could he have ventured into the dreaded forest of Dandak, and later Lanka, to confront the purpose of his life: the death of Ravana? Kaikeyi, being not just Dashratha’s favourite wife, but also a woman of courage, was the only one who could have ensured it. And so she conceives this plan where she demands her two boons, and the rest follows quickly.

Another folklore claims Kaikeyi’s father, King Ashvapati, who was conversant with the language birds spoke, once overheard two birds talking about the fate of Ayodhya, Dandak and Lanka, and how only one man—Rama—could save all three. Ashvapati recounts the incident to his daughter—the wise warrior princess of Kekeya. Astutely, Kaikeyi realises what she was fated to do—guide Rama to his destined path, braving the collective fury of her husband and son Bharata, as well as that of society, even if it meant dishonour and disgrace for her. That is why probably on Diwali day, Rama ‘forgives’ Kaikeyi; for us to later weave stories of her redemption.

(Kane is the author of Lanka’s Princess; The Fisher Queen’s Dynasty; Ahalya’s Awakening; and Saraswati’s Gift)

Yami’s Yearning

by Madhavi Mahadevan

The five-day celebrations around Deepavali end with a festival that, like Raksha Bandhan, marks the bond between brothers and sisters. Popular as Bhai Dooj, Bhau Beej or Bhai Phonta across different regions of the country, it has its origin in an ancient endearing tale of two children of the Sun.

Samjna, as the story goes in Markandeya Purana, could not bear the fierce glare of her husband, Surya, and shut her eyes in his presence. Angered, Surya said, “Since you always restrain your eyes, (one of the) twins born from you will restrain all creatures.” The frightened wife flickered her eyes, to which he said, “Since your eyes dart about, you will give birth to a daughter who will never be still.” The hexes engendered the twins, Yama and Yami (mentioned in the Rigveda). The boy is known to us as the ruler of Yamalok, the underworld, while Yami is the life-giving river Yamuna. He symbolises death; she brings renewal.

After giving birth, Samjna, unable to bear her husband’s company any longer, created a replica of herself, Chhaya (shadow), and vanished. The abandoned siblings, sensing an imposter mother perhaps, grew closer to each other. It was a time, we are told in the Maitrayani Samhita, when there was only day and no night. No dusk to draw a curtain, and no dawn to herald a new day, but an eternity of sunshine. Still, it was all good until the moment Yami discovered her brother sleeping, only to realise that he was, in fact, dead.

Her grief knew no bounds. She buried him, but couldn’t stop crying. Everyone consoled her—“Yama was a mortal”, they repeated—yet her tears flowed unceasingly. “My brother died today,” she said. A while later, when they approached her, she iterated in undiminished anguish, “My brother died today.” Understanding that the freshness of her loss meant that she was unable to turn off the tears—there was also the danger of the torrent drowning the world—the gods of creation got together and created night. Darkness fell and Yami slept. When she woke up, she was still heartbroken, but now she could say, “My brother died yesterday… a week ago… a month ago.” She missed Yama, but the passage of time healed her.

As the first mortal to enter the underworld, Yama, aka Dharmaraj, had the task of assessing whether the people who followed had lived righteously. Dispassionate as he was, he missed his sister too. One day, he paid her a surprise visit. Yami welcomed him joyously and cooked up a lavish feast. Sated, he gave her two wishes. “Please visit me again on this day every year,” she said. “And bless every brother who visits his sister on this day with a long life.” That day, the second in the waxing phase (Shukla Paksha) of the new moon in the month of Kartik, is also known as Yamadwitiya.

(Mahadevan has published two collections of short stories, Paltan Tales and Doppelganger, and is also the author of The Kaunteyas and The Forgotten Wife)

Region-specific Rituals

Punjab

For Sikhs, Diwali celebrations are not complete without commemorating the Bandi Chhor Divas or the release of Guru Hargobind (the sixth of 10 gurus) from imprisonment in the Gwalior Fort. Gurdwaras, especially the Golden Temple in Amritsar, are decorated with diyas and candles, and people engage in the Akhand Path. Langars or the community kitchens serve free meals.

Madhya Pradesh

A notable ritual here is the observation of Enadakshi, a day after Diwali when calves are bathed, decorated and worshipped in a practice called Vasu Baras. Rooted in agrarian traditions, it stems from the belief that cows are a symbol of prosperity.

Himachal Pradesh

In this otherwise tranquil state, a stone-pelting ceremony called ‘Pathar Ka Mela’ is held in the former princely state of Dhami village, about 25 km west of Shimla. Locals get together and fling stones at one another, and the blood from the injured is used as tilak for Goddess Kali.

Goa

In the coastal state, Diwali is a time to commemorate the victory of Krishna over Narakasura, the evil king of Goa. The rituals kick off with an early morning bath and the application of scented oil, a practice believed to emulate the god cleansing himself after killing the demon. The latter’s effigies are also set ablaze during the early hours.

Maharashtra

Bali takes centre stage here with the tradition of Bali Padyami, which celebrates the notional return of the king to earth. A puja is performed through which his symbolic footprints, also known as paduka, are adorned with flowers. Besides drawing rangoli and lighting lamps, traditional sweets are prepared and shared with the community.

Tamil Nadu

The custom of preparing a herbal powder mixture called Pavali Legium with coriander, cardamom, carom seeds, black pepper, cumin, dried ginger, liquorice, chitrak, pippali powder, jaggery and ghee is unique to the state. Believed to be a cure-all, the elixir is consumed a day before Diwali, and is traditionally had on an empty stomach.

Gujarat

Kanku Anamika is common among people of rural Gujarat wherein kanku or vermillion powder is put on grains and prayers are offered to the land and its tillers. It is believed that doing so results in

a bountiful harvest.

West Bengal

In Bengal, Diwali festivities are marked by the worship of goddess Kali. Temples, especially Dakshineshwar and Kalighat in Kolkata, burst into life with vibrant blood-red hibiscus flowers as an ode to the essence of adishakti or feminine power. Celebrations commence the day before Diwali with Bhoot Chaturdashi, as part of which 14 diyas are lit at temples and homes to ward off the evil eye.

Rajasthan

Throughout various regions of the western state, people use lamps filled with kohl to dispel negative forces. The protective mixture is created by adding ghee to coal powder and shaping it into compact spheres inserted with a cotton wick. The lit lamps are then placed at the main door and windows.

Odisha

Kauriya Kathi is a unique ceremony to honour one’s ancestors in Odisha. On Diwali, locals burn jute stems to summon their forefathers from the heavens and seek their blessings. The offerings are placed in a sailboat-shaped rangoli.