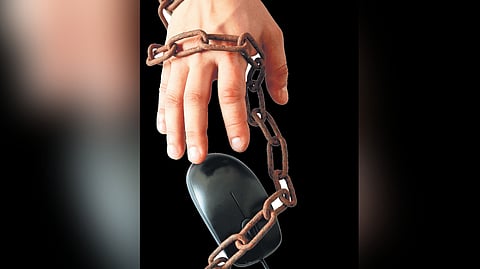

Web of Slavery

Nandan Sah was living an ordinary but peaceful life at Behra Sikta in Bihar’s West Champaran. For this 30-year-old father of three, the proceeds from running a photocopying stand at home contributed to the budget of the joint family he was part of. Sah has a diploma in computer science; he fancied a better vocation. To his joy, a dream job came calling last December when he was offered a position as a data operator in a foreign country. The salary promised seemed like a life-changer, and Sah signed up immediately. For a fee of Rs 1,30,000, his Delhi agent placed him in Cambodia.

Sah packed his bags for a better life. Only, life became worse. He was put to work on internet scamming operations with a team of others trapped like him. Sah just couldn’t take it, not the long hours, not the criminal activity. He protested, and was beaten to an inch of his life. He was given electric shocks and tasered, and left to die alone in a Cambodian forest. Nearby villagers helped him call for rescue. Sah is back home now, battered and impoverished, but way wiser.

Sah’s brutalisation was like a computer algorithm. Another unfortunate young man who rebelled against forced criminality was run through the same. “They used tasers, again and again. They hit my knees and joints with sticks. When we asked for water, they beat us more. I was bleeding, and sure I would die,” he says.

Sah’s ordeal continues; it has only mutated into a search for justice. “I am at home now, recovering, and have begged my agent to return my money,” Sah says. The agent also took him to a hospital for treatment, but without an FIR, no one was willing to help. With no other option, Sah returned to Behra Sikta, and tried filing an FIR there, but was told that the “issue” was beyond the jurisdiction of that station. He has since written letters to the Prime Minister, Ministry of External Affairs, Union Minister S Jaishankar and Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, all with a 16-GB pen drive that has “proof of torture and accounts of others”.

“It is my prayer that someone helps us as we are left to die in such scam companies. I am poor and cannot afford a lawyer,” says Sah. He revealed two mobile numbers, both of Indians still stuck in a Cambodia fraud factory, but when contacted they refused to speak for fear of their lives.

Nandan Sah's plight is a classic example of a new form of exploitation and human trafficking called cyber slavery, where computer-literate job-seekers are lured into cyber-scamming outfits offering attractive salaries for jobs that sound like marketing and currency trading. These dupes are almost always made to pay significant amounts of money to get the ‘job’. They are then put to work, scamming people with a myriad of fraud business opportunities and fake online romantic liaisons, mostly in the West and wealthy sections of developing countries. Long hours are par for these cyber slavery courses; those who can’t keep up are usually subjected to brutal punishment. In short, cyber slavery is human trafficking for forced criminality or exploitation in scamming activities run on the Web.

Bad news broke through the woolly clouds of the election cycle last week: 5,000 Indians were found to have been forced into cyber slavery in Cambodia. These unfortunate captives were being bullied to cheat people living in India, extorting money by pretending to be law enforcement officials who said they had found contraband or suspicious materials in parcels addressed to their targets. They allegedly duped their marks of at least Rs 500 crore over the past six months.

The Indian government had to swing into action, and it did. Early last month, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) held a meeting with officials of the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (Meity), the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C) and other security experts to draw up a strategy to rescue such ensnared Indians in Cambodia. The effort is beginning to yield results: a group of 80 Indians has been rescued from Cambodia by government operatives. Some are still stuck in Myanmar, however, since they entered the country illegally.

Cyber slavery is a three-headed monster, encapsulating human trafficking and forced labour to create a vast criminal empire. It’s relatively new, having been seeded during the Covid pandemic, but estimates of the number of cyber slaves run into the thousands. And that’s a conservative figure. The Humanity Research Consultancy, a non-affiliated group dedicated to the fight against slavery and trafficking, estimates some 25,000 cyber slaves toiling in South-East Asia, largely in Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos and the Philippines. Others say the figure could be four times that. No wonder then the issue was discussed at the ASEAN meet in May last year.

Evidence reveals that cyber slavery is exploding. It began with The Virus: the ban on travel from China during the pandemic meant Chinese gangs running gambling and casinos in South-East Asia were cut off from their clientele. Given that these gangs had their own places, the lucrative world of cyber scams was a throw of the dice they couldn’t resist. All they needed was people familiar with English and computers. So the personnel had to be lured in. Making them work long hours and abusing them for ‘non-performance’ was the forced labour bit, and the criminal defrauding of nameless victims on the world wide web completed the triad.

A worrying aspect of cyber slavery is its expansion to conflict. Sufiyan from Telangana is an example. The prospect of a high-paying IT job led him right into the middle of the warzone in Ukraine. Deceived into joining the Wagner Group, a mercenary force fighting for Russia, 22-year-old Sufiyan made an SOS call from the warzone even as shells exploded all around, killing a Gujarati boy next to him whom he knew. This Narayanpet boy’s family has contacted the Indian embassy in Moscow, appealing to officials for his safe return. There’s no word yet. Another Hyderabad lad, Mohammed Afsan, 30, was reportedly killed in bombings near the Ukraine frontlines. His family awaits the body.

Sufiyan’s contract was to serve in the armed forces of Russia in an IT job, on a ‘letterhead’ from the ministry of defence of the Russian Federation for a military service contract in Kostroma district. Enticed by the Rs 1.5 lakh per month salary, travel included, he and three other young men from Karnataka’s Kalaburagi district ended up as cannon fodder on the Donestk front in eastern Ukraine. Another 60 Indians are believed to have been drafted similarly through an agent running a YouTube channel in Maharashtra.

Cyber slaves are being recruited from across India. The Rourkela Police recently detected a cyber crime syndicate with links to cyber slavery, stock fraud, suspected forgery of passports, etc. The accused were arrested following 210 complaints from India as per data from JCCT Management Information Systems (JIMS) of I4C, MHA. The accused—of their own volition—joined a scamming company in Cambodia where they posed as girls to target Indian males through a dating app called Happn.

Once they established a modicum of trust, targets were convinced to invest in crypto currency trading. The perpetrators later joined another company focused on investment scams by creating fake online applications showing Indian stock market fluctuations, targeting Indians to invest in fake stock options by showing fake returns online. Gifts were also offered to sweeten the deal. Victims were first lured into investing, getting paltry initial returns. Then the app stopped payouts. This gang confessed to defrauding about 40 people, one of Rs 2 crore. In the world of cyber slavery, closing the deal on a victim and extracting money as the final step is called pig butchering, a term that is rather apt for the final act of these crimes.

In the swampy world of online and digital scams, the runaway growth of cyber slavery shows how human capital is expendable—riding the hopes of the less fortunate or those looking to make a quick buck illegally. India’s job hopefuls from the lower strata are easy targets. The I4C, entrusted with providing a framework and eco-system for law enforcement agencies (LEAs) for dealing with cyber crime, helps investigate and research cyber crimes and forms the knowledge arm. The understandable greed of job-seekers and the criminality of syndicates working through what is called social engineering feeds cyber slavery.

In 2023, some 13 lakh cases of online financial fraud were reported in India, with about 1.41 lakh of them related to social media. Many job-seekers acquiesce to the illegal nature of work, and the few that oppose it are held captive, their documents confiscated.

Social engineering

Social engineering in cyber slavery, as opposed to the innocuous use of the term in electoral politics, is the practice of deceiving people by gaining trust to obtain valuable information—phone numbers, bank account details—followed by a cyber attack (phishing, whaling, baiting, smishing, etc).

A United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) policy report on casinos, cyber fraud and trafficking states that at least 1,50,000 hapless youth are stuck in Myanmar in fraud factories. Over 50 per cent of these scam factories originate in South-East Asia, which is

a breeding ground. There is growing evidence, however, that locations like Dubai and Georgia (in the Russian Federation) are also witnessing a rise, according to Dr Rakshit Tandon, risk advisory and cyber consultant, CID, Haryana Police, and advisor to state cyber crime cells.

Terrifying Ordeal

One of Sah’s co-workers was being taught to use social media to communicate and lure individuals into divulging personal details. His salary was $800 at that point. This can go up to $2,000 in rare cases. Along with 16 others, the new recruits were taught to influence individuals, to work on Facebook ads to connect with customers. “My job was to chat with customers and to convince them to share their WhatsApp number, which was given to a senior who worked on financial fraud. ‘Give your child a great future,’ one ad promised, and we targeted anyone who commented, liked or shared the ad,” he says, preferring to remain nameless.

Indians often scam Indians, because of cultural, language and accent similarities.

The UNODC report quotes an NGO representative saying, “They (agents) have a quota—you’re supposed to trick people into the scam compound. There is a $300 payment for each new recruit, so it’s an incentive. The pay offered is usually the equivalent of around $1,000-1,500 per month with generous benefits—free food, housing, travel costs, etc.” Rajat Ahlawat from Crystal Intelligence is

a crypto investigation and intelligence researcher based in the Netherlands. “These individuals are monitored, unable to leave the premises, toilet breaks are limited. Most compounds have restaurants, gambling and drug dens, especially in Myanmar where a lot of MDMA is produced,” he explains.

After training, the pig butchering commences when scammers ‘fatten’ (in profit terms) their victims by slowly building trust before moving in for ‘the kill’, as the UNODC policy report puts it. Beware of ads promising “too much”—as job-seekers or internet users, says Ahlawat. “Awareness is crucial so that others are not sucked into the cyber slavery syndicate,” he adds. Thus, the increase in theft of personal data owing to cloud misconfiguration, new ransomware attacks and increased exploitation of vendor systems shows skyrocketing figures: In the US, at least 42 million records were exposed by data breaches between March 2021 and February 2022. Tandon insists, “Malware is increasing substantially, and personal identities are compromised.

I believe a ‘zero trust’ attitude is important. Do not trust a phone call offering work-from-home and large amounts of money. Some use fake videos of Virat Kohli, Priyanka Chopra and Narayana Murthy to entice people into such scams,” Tandon says. “What is unnerving is that apart from social media, even the trusted LinkedIn has been targeted with fake profiles to dupe people to pay for jobs, visas, travel—professionally done. Well-known TV journalist Nidhi Razdan was duped during the pandemic when she got a mail appointing her to Harvard.”

Often, pig butchering involves gaining trust to inveigle bank details, informing one of winning a lottery, having received a dubious package, writing Google reviews, etc., and then asking one to join Telegram on promises of high financial gains. “Some chats are so believable, as hundreds share screen shots of money invested, paid, returns received that the innocent internet user falls prey. Be careful, always look for a time stamp on such chats, and don’t believe any offer without due diligence,” advises Tandon.

Too Good To Be True

A source in cyber crime safety observes, “Offer letters given are extremely detailed, and professional. The thumb rule for any online interaction is—don’t believe anyone upfront. Do not share personal details or documents, and do not click on links. Double check veracity of company, website, verify with agent lists that government websites update. Professionally conducted bogus job interviews follow. Often, to make the job ads more legitimate, scamsters have started to fraudulently use the names, logos and branding of real companies,” says Ahlawat.

“In India, there are also romance camps, and guaranteed investment scams where the perpetrator develops a relationship with the victim,” adds Ahlawat, stressing that social engineering and human greed play a huge role in luring individuals.

Deeply concerning is the human trafficking angle—most workers are trapped inside a compound for 15-16 hours of work a day. In case a new recruit is unable to “scam” (about five per cent are unable to), torture and beatings ensue. It can be noted that many individuals might not be forced to commit online scams and fraud, rather, may be trafficked for forced labour or sexual exploitation too, according to media reports. The UNODC report cites the case involving a 13-year-old girl recruited from China, for the ‘sales department’ of a scam compound in Cambodia. When she did not perform well conducting online scams, she was sold into prostitution by the organised crime group.

Tough Nut to Crack

The deeper malaise lies in policing and legal recourse of cyber slavery, which due to cross and open borders, the lack of jurisdiction and legal framework in the country of crime versus origin, makes it almost impossible to redress or police.

Due to the cross-border issue, international pressure through the UN has often been applied on the Cambodian government. Sometimes enforcement officials are sent into suspected cyber slavery compounds to check if individuals are being held against their will. All these scam compounds are heavily guarded and barb-wired; the confiscation of documents of people working there is the rule. “India is a fertile ground because of its skilled labour in terms of IT skills, and also because many of these youth want a better paycheck/life,” says Ahlawat.

Tandon believes increased awareness of the practices can help. “Every week the government of India issues a high-risk warning to protect incoming threats, to install only trusted apps, etc. Cyber hygiene or digital quotient is crucial to avoid falling into such traps with education and awareness. Everyone uses a smartphone, but few know what the different codes signify; digital literacy is missing. Someone gets a call from a shopping site about a package, and they say, ‘We are sending you a number to call an agent, routing it through a company line, pls dial *401*.’ Don’t. This is a code for call forwarding, from the moment you do that your device is in their hands.”

A little knowledge can also be devastating. “Influencing the mind with the help of digital content is an addiction, a form of slavery. I have seen many gamers lose lakhs, young boys committing suicide. Recently, an IT CEO in Bengaluru lost `2.3 crore in the Fedex scam. Content which should reach people is not reaching them, and scamsters and their dodgy algorithms are ruling the day,” says Tandon.

Forewarned, Forearmed

In a macro perspective, Rostow Ravanan, a cyber expert, chairman and CEO, Alfahive Inc, realises the gargantuan task of policing cyber crimes and cyber slavery. “Inter-disciplinary collaboration, innovative legal frameworks and enhanced technological tools are needed with collaboration between experts and policy makers. Updating laws to encompass digital exploitation and enhance enforcement mechanisms for a more robust system, strengthening international cooperation and raising awareness, and defining clear legal boundaries are very important. Empowering law enforcement with specialised training and resources is needed too,” says Ravanan.

While investment in technology and people can address this nascent organised crime industry, Ravanan adds, “On the technology front, more infrastructure—physical, computing, etc.—dedicated labs, both owned and co-located with academic institutions, partnerships with industry (with appropriate safeguards), launching bug-bounties, practices for whistleblowers to submit cases anonymously, etc. can help.”

The lure of a dream job, or big bucks and indulging in illegal scams of their own volition will always find takers. Delving deeper, Ravanan lays out more steps: “Introducing rotational/time-bound assignments for professionals and academicians to be part of law enforcement task forces, connecting with the open-source community, specialised and in-depth training of the Indian Police Service, establishing a specialised cyber crime cell at national and state levels, and a cyber crime task force within regulators like RBI, SEBI, etc.”

India is struggling to deal with cyber slavery and cyber crime, yet it is among the few where law enforcement when dealing with crimes of such nature is a state issue. Ahlawat feels scammers are fearless because of this. In one case, a Nigerian man was confident he would not be held accountable, because of jurisdictional issues.

For the local police task force to investigate a cyber crime originating elsewhere is a tough ask. The legal framework would require, in Sah’s case for instance, the Delhi Police to send a team to Bihar, and locally to the victim’s village where the police have no incentive or know-how. Most South-East Asian countries where these factories operate have open borders. In places like Myanmar with its military junta and the States Border Guard Force, bribery is rampant, and a blind eye is turned to cyber slavery rackets. Another suggestion is to form a global task force, akin to what was done to combat terrorism and drugs.

Save The Youth

“India needs to go beyond knee-jerk reactions, and streamline the process. Most importantly, cyber crime should be investigated by a central agency,” says a cyber crime expert. Another expert adds, “The government should invest in a track-and-trace tool. Currently, all the police officials use the open source versions.”

Finally, the ground reality is bone-chilling, terrifying even, because of the insidious nature of internet scams, and human greed. Ravanan agrees that track-and-trace methods offer promise, but their effectiveness depends on implementation.

A robust response that can fight cyber slavery will take time to develop. Till then, thousands of Indians will continue to be exploited in these 21st-century digital hell-holes, and thousands will be trafficked into this web of slavery every year. ‘Save’ has acquired a whole new meaning in the digital age.

Scam-proof Yourself

● Do not trust social media ads on Google or Facebook

● Be cautious about investment schemes and apps offering high returns

● Check veracity of company, account details, etc.

● Do not transfer money into random accounts

● Desist from any financial transactions with unknown entities, individuals or companies

● While using dating apps, confirm identity, ask for reference, proof, before embarking on any relationship

For Job-seekers

● Do not answer ads for IT- or tech-related job without checking company on government sites

● If the offer is too good to be true, IT IS

● Check companies, address, phone numbers, email ID, call and reconfirm

● Check official agent lists on government websites

The Tandon Protocol

Cyber evangelist Rakshit Tandon on how to protect yourself and your smartphone

● Keep your mobile device OS updated for latest security threats

● Keep all apps updated from playstore and App Store

● Be smart and careful while giving permissions to apps installed from playstore or App Store

● Don’t install any apps from unknown sources—especially any app file sent by an unknown source

● Don’t press any USSID codes on mobile if caller is asking to do that—like *401* is used for call forwarding

● Never install any unknown app

● Keep all accounts safe with multi-factor/two-step verification on

● Don’t keep any personal credentials in photo gallery—like Aadhaar/PAN Card photo

● Use DigiLocker to secure such data or keep it in drive or cloud

● Have a zero trust behaviour for calls/SMS/message, etc. Verify before any action

The Law Needs New Teeth

The war on cyber crime and cyber slavery needs new tools and processes:

● Collaboration among law enforcement agencies at the state, national and international level, and between tech companies and governments to track and prosecute cyber criminals

● Stronger regulations on digital transactions that can hold tech platforms accountable for facilitating fraud

● Proactive measures by tech companies to detect and prevent fraudulent activities

● Enhancing public awareness and digital literacy to recognise and report fraud

● Implementing robust identity-verification measures to prevent fraud

● Developing advanced cyber security measures to detect and mitigate online threats effectively

● Facilitating seamless information sharing across borders to track and apprehend fraudsters effectively

● Establishing global databases to track fraudulent entities and swift extradition agreements could deter scamsters from exploiting legal loopholes

● Setting up a national level investigative organisation to attack types of cyber crimes which cut across state boundaries