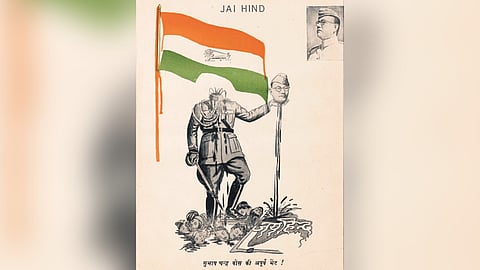

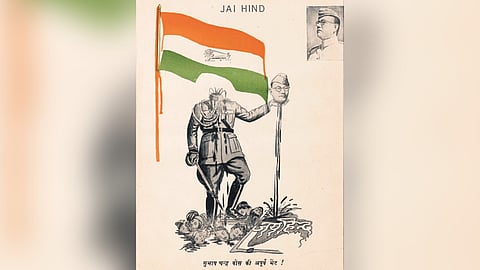

You have to walk a little more than half a circle across the art gallery to spot one of the most unexpected pieces in an exhibition on the Hindu deity Kali. It is a poster featuring a decapitated Subhash Chandra Bose holding his severed head with blood dripping down from his hand. The poster, printed at “National Press Cawnpore” was circulated widely during India’s freedom struggle and epitomises Bose’s iconic words, “Give me blood, I will give you freedom”. The reason why it is part of DAG’s ongoing exhibition, Kali: Reverence and Rebellion is its appropriation of the iconography of Chhinnamasta—one of the 10 Mahavidyas or the 10 aspects of the divine feminine.

Barring three pieces, the rest of the over hundred works are from DAG’s own archives. They range from miniature paintings from Bengal and Jaipur, and colonial-era works to modern and contemporary masterpieces. Their relevance, however, goes beyond mere aesthetics. Art historian Gayatri Sinha, who has also curated the exhibition, explains how the symbol of Kali traverses the idiom of worship to become the face of resistance, and therefore, remains eternal in its resonance.

“Kali steps out of the realm of pure mythology and into India’s social space. In the 20th century mainly, and even before that, she was evoked in times of social crisis. If we take the example of the nationalist movement, the invocation of Kali by people like Subhash Chandra Bose or Aurobindo places her as if she was leading the struggle.” She adds, “So, Kali is not seen as a remote goddess who is accessible only through years of sadhana. She is seen as eminent, and she becomes a participant in the broader social context. That’s what perhaps distinguishes her from other mythic figures.”

The ‘Subalternity’ segment of the exhibition, for instance, shows how Kali “emerges as an omnipresent cultural and social force” through a mix of sculptural and popular art works. It features a collection of paintings of the deity done in the quintessential 19th-century Kalighat pat style. The small-scale paper works executed in colourful bold strokes, were often available outside the Kalighat temple in Kolkata for “pilgrims who would take them back as souvenirs”.

The 19th-century was also the time when British rule in India was at its peak. Having firmly established their reign, the English now invested in literature giving a glimpse of the “orient” to those back home in Europe. The depictions, however, were anything but flattering. The exhibition reiterates literary critic Edward Said’s readings in orientalism, where the imperial powers looked at the colonised through a derogatory lens, in a painting titled ‘Ceremony of Washing the Goddess Cali, and the idol Jagan-Nath’ by British engraver John Chapman.

The watercolour-on-paper work shows an idol of the goddess on a boat with a group of worshippers. The exhibition catalogue notes that it is “erroneously” titled, and it is in fact a depiction of the immersion ritual that is undertaken after the Kali Puja in Bengal. While the “iconography of the goddess is accurate with her garland of skulls, a gently lolling tongue, a severed head and a scimitar”, its representation in a “caricatured manner” reveals a “stark Oriental bias”.

In the same vein is another work—a lithograph titled ‘Procession de la Déesse Kali’ (Procession of procession of the goddess Kali) based on a painting by Russian artist and traveller Prince Aleksandr Mikhailovich Saltuikov. The monochromatic image shows devotees gathered around a Kali idol in celebration. Sinha notes: “Broadly coinciding with the colonial perception of Kali as the goddess of thugs, the print depicts a nocturnal procession of Kali and her supposed army… This lithograph reflects Saltuikov’s attitude towards Kali as the terrible goddess of the cult of Thuggees.” It is interesting, therefore, to note how Sinha has placed these works across the one featuring Bose’s call for action against the British.

For some, Kali is a figure of reverence, for others, she is the symbol of resistance, but there exists an in-between on the spectrum where she finds her way into artists’ imaginations in their unique styles.

A sublime work here is Madhavi Parekh’s ‘Kali on Mahishasur’. Executed in Parekh’s quintessential rural folk style, the acrylic-on-paper work shows the deity on top of a tiger. Its appeal lies not just in the “naive imagery and flying figures”, which provide a fantastical setting, but also in Parekh’s decision to shift her usual colour scheme—bold and bright—and go for monochrome.

There’s only a speck of colour—the yellow of the crown and the red of her tongue and bangles—and it renders the image with a sense of strength. “The potential Kali suggests is that the feminine does not have to be the passive role. It can be active, vigorous and victorious. Kali bucks the trend of patriarchy and that’s why she is such a striking figure.”

Ancient social mores or modern interpretations; Kali is for forever.