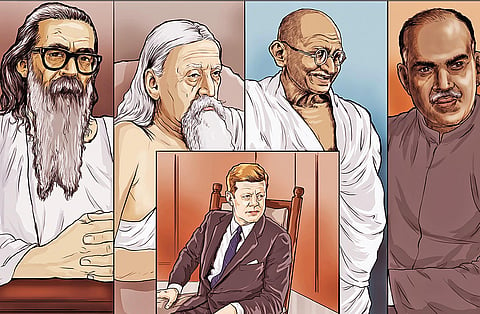

When he was asked a line of thought on the Korean conflict sometime towards the end of June 1950, Sri Aurobindo replied that the whole affair was as plain as “pike-staff. It is the first move in the Communist plan of campaign to dominate and take possession first of these northern parts and then of Southeast Asia as a preliminary to their manoeuvres with regard to the rest of the continent—in passing, Tibet as gate opening to India”.

In 1949, while he was revising his opus, The Ideal of Human Unity, against the backdrop of current events, Sri Aurobindo had included a ‘Postscript Chapter’, in which he clearly wrote on how the Communist powers would eventually “overshadow with a threat of absorption South-Western Asia and Tibet” and might attempt to “overrun all up to the whole frontier of India, menacing her security…”

If one were to go by the editorials of the fortnightly Mother India, then published from Mumbai and edited by one of Sri Aurobindo’s most articulate and politically astute disciples—KD Sethna—Sri Aurobindo was against the move of according a hurried recognition to Communist China.

Sethna is on record having said that the Mother India editorials, between 1949 and 1950 were whetted, altered and cleared by Sri Aurobindo himself before the issue was finalised.

On China, the Mother India editorials were remarkably prescient and sharp, “Whether India recognises Red China or no, she will never cease to be marked out by the latter as a field for subversive activity…” and therefore, “not to see Red China’s basic antagonism to democracies like India is political childishness”.

Nehru’s “much-vaunted neutrality”, his “unwillingness to be teamed up with either bloc” will not make Mao the “least bit affectionate” towards India, it argued.

On Nepal, another Mother India editorial was equally farsighted when it warned Indian policymakers that India’s recognition of Mao’s government “will not stop his coveting Nepal”.

Interference in Nepal was an “item already included in the Communist plan for self-aggrandisement in Asia”.

Another editorial written sometime towards the end of 1950, when China had already invaded Tibet, spoke of “Mao’s mechanised millions” posing a threat to democracy in the region.

“The significance of Mao’s Tibetan adventure”, the editorial noted, “is to advance China’s frontiers right down to India and stand poised there to strike at the right moment and with the right strategy… the primary motive of Mao’s attack on Tibet is to threaten India as soon as possible…”

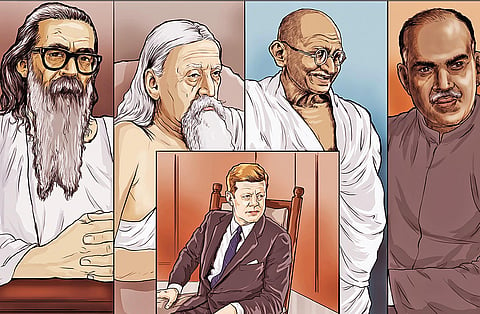

In 1963, President Kennedy was shown Sri Aurobindo’s predictions. Poring over them several times, Kennedy blurted out to Sudhir Ghosh, diplomat, parliamentarian, who had presented him a copy of The Ideal of Human Unity following a meeting at the White House, that “Surely there is a typing mistake here. The date must have been 1960, not 1950.

"You mean to say that a man devoted to meditation and contemplation, sitting in one corner of India, said this about the intentions of Communist China as early as 1950?” To think that Sri Aurobindo foresaw all this between 1949 and 1950, while Nehru indulged in a rudderless “Non-alignment”, devoid of all strategic depth, is indeed striking.

On December 6, 1950, just a day after Sri Aurobindo’s passing, the Indian Parliament discussed the “International Situation”.

Dr Syama Prasad Mukherjee in a detailed intervention displayed an incisive understanding of Communist China. Cautioning Nehru against adopting a policy of drift and indecision vis-a-vis China, Dr Mukherjee argued, “We must also guard against the possibility of trying to please everyone. That is a dangerous pastime.”

On China, he articulated what ought to have been free India’s approach towards the hegemon.

“We have no quarrel with China so long as China is anxious for the liberation of her own people. Everyone will have sympathy with the Chinese people but if China takes on herself the task of liberating other people also who may not be anxious to obtain liberation at her hands, naturally that creates complications which will affect not China alone, but the rest of the world, particularly Asia.”

Twelve years later in 1962, the ideological and political justification proffered by communist cartels in support of China’s aggression on India was the same “liberation” theory.

On China, Sri MS Golwalkar too displayed a far-seeing vision. In one of his last interviews, Guruji observed that the Chinese “have not broken with their past. Wait for some more time. All their traditional ways will become patent again. Their present designs to spread their tentacles of power and influence are in keeping with the tradition of their old emperors.”

But just as he foresaw the collapse of the Soviet Union, for Guruji, Communism in China was “also a temporary phase.”

On China, all these stalwarts could see what Nehru sadly did not. Today once again on China, Modi sees what Rahul cannot!

ALSO SEE: