Last week, I woke up to a woman sitting on vigil beside her newly married husband’s dead body, and went about my day as usual. Social media is not for sissies. I finished other tasks, but again, my social media timeline kept tossing bits and pieces at me—parts of New Delhi going up in flames, parts I had visited a decade ago, owing to my earlier life in fashion design. I’d walked the alleyways to collect the work I’d given out, made friends with the women living in the shanties and the buildings piled over each other under a maze of black electric cables. Shared a meal or two with some of them.

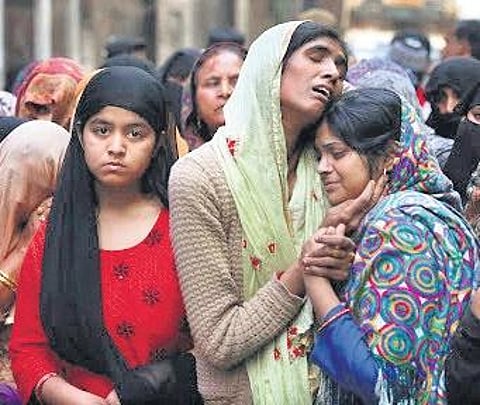

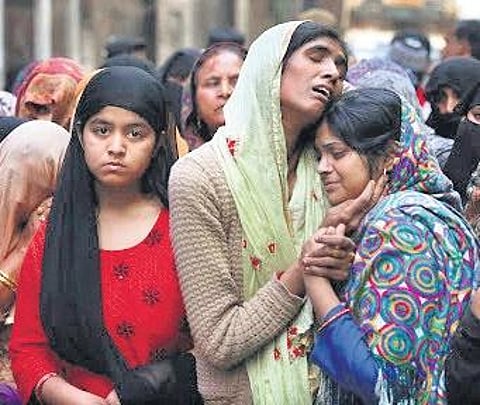

These were women I had nothing in common with. Their hands were skilled, I worked for an export house that needed those skills. That was all.The pictures have not stopped, and I cannot stop thinking of how those friends I made years ago might have fared during this spate of violence.Two sides to every story, they say, but there’s one group that has suffered the most—underprivileged women. Women in India, and perhaps the world over, often have the most to fear in times of violence, because in many societies, their bodies are considered battlegrounds of family honour. Of male pride, if you really look at it. Though reports are yet to emerge of sexual violence against women, I see the sleepless eyes in the videos and pictures of women who have suffered in the Delhi riots on my timeline. Women displaced because their homes were burned, and they escaped at 3 am under the cover of darkness, dressing their children in clothes still wet from washing.

Women returning to homes filled with stopped clocks, empty vessels and cupboards, ash and soot instead of clothes and documents. Mothers mourning their sons gone out to buy milk, never to return. Women jumping from terraces, getting the limbs of their children broken in the process. Women still struggling to feed their children because of the increased prices of food and milk. Then there are the women journalists who covered these events. Women at work who gave out different names and wore different clothes, according to the neighbourhoods they were heading to or escaping from. And then there is us, the women who are far away from it all, in our privileged cocoons. Some trying to use that privilege to protest against what they see as a government-sanctioned pogrom. Others using the same privilege to support the government’s policies. Taking to social media to fight proxy wars, exchange insults, to incite, to grieve, from both sides of the divide.

These are women, too. Not ones who were affected by the violence (almost everyone able to read this right now either has had no direct experience, or is able to escape from the horrors, one way or another), but engaging in the discussion of it. I belong to this class of women—who are far away and insulated from the streets where the carnage took place, yet cannot or will not keep away from it, because it is everywhere on social and traditional media, or perhaps because we either believe that we are somehow responsible for the situation, or believe that others are.

The reality is, each one of us is part of it. If not by commission then by omission, because we are all part of the system that allows violence, greed and hatred to continue unabated. Hatred and violence have been part of human nature, and it would be naïve to think we can change it any time soon, but we can improve the human condition. The majority and the powerful, be it from any communal belief system, will always resort to domination—a very male quality. Our lot as women is to be either victims, enablers, or spectators. Toxic masculinity sets it all off; those who create and sustain belief systems for their own advantage, those who either worship women or render them invisible, or both at the same time, those who divide and rule, largely go unpunished. The violence remains, its path paved by greed and hatred. It turns cyclical. Those who suffered today will retain the trauma and carry forward the toxins into the next generation.

The question for women then is whether they should continue to stay relegated to their roles as victims, enablers and spectators. Or should they stand up and initiate a new cycle, one that is built and focused on compassion? On healing, not revenge. On justice. On seeking to limit the toxins of human nature, because as history tells us, they cannot be eliminated. On cooperation, not competition.Be it on social media, or profession, or politics, I wonder if there can ever be a rise of mutual nourishment, of making friends, of gratitude and forgiveness, despite a history of violence? Could women lead that movement?I once watched a documentary on white pelicans fishing in random groups. Perfect strangers often team up to form a semi-circle, driving schools of fish towards the shore. All of us might do well to learn from those pelicans.

Damyanti Biswas

Author and activist

Twitter: @damyantig