Another pilgrimage season in Sabarimala is in full swing, and another set of controversy has erupted. This famous pilgrimage place deep inside the Periyar Wildlife Sanctuary has been in the news for all the wrong reasons for the past few years. Five years ago, it became the battle-ground for left ‘liberal’ activist politicians who were convinced that Indian women’s liberation would come from them being allowed in this temple and the right-wing conservatives who were gleefully rubbing their hands in anticipation of a golden opportunity to whip up religious sentiments and convert them to votes. Unfortunately, both ended up losing in the next elections. The new controversy now is the failure in crowd management that has resulted in huge inconvenience to everyone concerned and political parties of all hues have jumped into the controversy, accusing each other and trying to gain mileage out of the total mismanagement by the Dewasom Board.

In all these political machinations, there are two things that political parties have conveniently forgotten. One is the temple’s sanctity, and the second is the pilgrims. The forest shrine of Sabarimala is unique among many pilgrimage places in India. It opens only for a limited number of days in the year. It is located in an environmentally fragile place, deep inside a national tiger sanctuary. The concept is that of a forest shrine that is secluded from civilisation. One needs to undergo many privations of mind and body for some time, both during the penance period and during the pilgrimage.

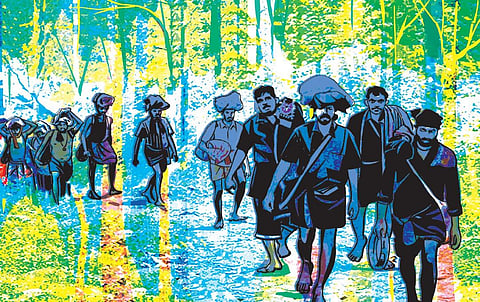

By custom, one needs to follow 41 days of strict austerities where one needs to avoid all non-vegetarian food, take a bath before sunrise, sleep on the floor, practice celibacy, wear no footwear, tell no lies or cause harm even inadvertently to any living being, meditate and undergo many such penances. The pilgrim loses his or her identity and name, and everyone becomes either Ayyappa or Malikapuram based on gender. The differences of caste, creed, language or religion are forgotten, and the pilgrim is supposed to walk through dense forest for days without footwear or any protection other than his belief in the forest god of Ayyappa, which is himself. It is believed that the wild elephants and tigers that abound in this holy forest won’t harm anyone making this pilgrimage.

If the pilgrim forgets this concept of ‘Aham Brahmasmi’ or ‘I am Ayyappa’, it is written in bold letters at the temple entrance—‘Tatwamasi’—or thou are that. In short, this long and arduous journey of self-reflection is to remind oneself about oneness with nature and the true nature of one’s self. It is also about developing self-control and overcoming prejudices based on caste, creed and other identities that get attached to one’s ego. By breaking the coconut at the temple entrance, the pilgrim is again reminded about the breaking of the ego.

Unlike many temples in other parts of India, Sabarimala’s primary purpose is not having a darshan of the idol. Kerala temples are not designed as places for congregational worship or for having a glimpse of the murti. Among many forms of worship in Hinduism, there is nothing right or wrong about any method. The problem becomes an issue when the Sabarimala shrine is turned into a place of congregational worship and idol darshan like other temples, forgetting the basic tenets. The issue becomes a crisis when the pilgrims forget the concept of penance and Ayyappa and throng the temple like a cheap tourist destination.

They come in luxury buses and cars, flood the fragile forest with toxic fumes, litter the pristine areas, and convert the holy Pampa River into a garbage drain. This is nothing new for anyone who has visited India’s temple towns. The holier the town is, the filthier we make it. This crisis turns into a disaster when this desperate need of millions of casual pilgrims—who have no time for penance but want a few microseconds of darshan in a place that was never meant to have so many pilgrims—meet the incompetence and greed of the state Devasom Board, which manages the temple.

This disaster turned into a catastrophe when the state administration used the shrine as a cash cow to milk and fill their empty coffers. In the years we are lucky, we get away with unspeakable inconvenience to the thronging pilgrims who have to wait in the haphazardly erected, ridiculously planned clutter of shacks or in the hot sun for hours. In unfortunate years like 2011 or 1999, we witness stampedes that have taken hundreds of lives. As if they are not satisfied with the mess that has been created so far, the central government has joined hands with the state in putting up an airport near the temple, deep inside the jungle, to attract more tourists.

The use of the word tourist is deliberate as most people turning Sabarimala into a mela ground no longer deserve to be called pilgrims. Woe is to the genuine pilgrims with no place to go without jostling and fighting through this throng. The journey through the thick jungle teeming with tigers and wild elephants of yesteryears was far more meaningful and divine.

They can clear the entire Periyar wildlife reserve, and still, won’t be able to accommodate the number of tourists who are going to masquerade as pilgrims in the coming years. Unless we restrict the number of pilgrims who can visit the forest shrine, we are heading towards a Sabarimala metropolitan city built of shacks and plastic sheets with a filthy drain for Pampa river. Why not have a transparent lottery system that would select the people who can visit the shrine in a particular year? If you get the lottery, it is Lord Ayyappa’s will, and he is calling you. If you don’t get the lottery of visitation, who are you to question the lord’s will? And if you don’t believe in Ayyappa’s will, why are you going there in the first place? This could be a solution with one caveat. This would kill the cash cow that is feeding many politicians and bureaucrats’ pockets but may save Ayyappa’s divine forest and the shrine.

Anand Neelakantan

Author of Asura, Ajaya series, Vanara and Bahubali trilogy

mail@asura.co.in