In a recent judgement, the Kerala High Court devised a bizarre directive on using elephants for temple festivals. The directive includes maintaining a gap of three metres between elephants, a five-metre distance from fire torches, and an eight-metre buffer for spectators, besides norms for adequate rest and safe transportation of the beasts. At first glance, this directive looks progressive and humanitarian.

Much cruelty is inflicted by taming the elephants, and the hardships these beasts face during the festival season are indescribable. They are chained for hours, forced to stand in the heat without proper food or water, listening to the high-decibel drumming amid a huge crowd. As most temple festivals happen around the same time, they are transported from one temple to the next in cramped trucks for hours. They have not evolved to take this torture, and often, they go berserk, resulting in tragic accidents and stampedes.

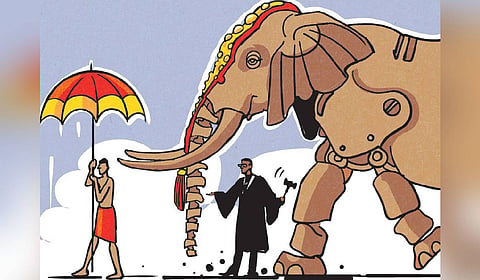

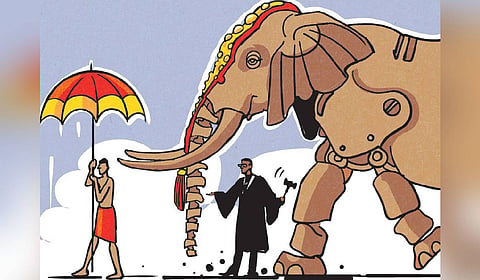

The Cochin Devasom board had challenged an earlier directive, stating the procession of elephants is an essential religious tradition followed for many centuries. The deity is mounted on caparisoned elephants and taken on parades. However, the honourable court, in its wisdom, has decreed that it is not an essential practice of Hinduism. One is curious to know how the court arrives at what is a necessary practice of a diverse religion like Hinduism and what is not. Hinduism has no central tenets, books, church, etc, to dictate what is essential and what isn’t.

Many temples practice animal sacrifice in India. Does that constitute an essential practice? If so, should other temples that don’t follow the same be guilty of breaking the fundamental tenets of Hinduism? Or are the temples like Kamakhya in Assam, where such practices exist, violating Indian law? Is taking the life of a goat or chicken in the name of worship and tradition any less cruel than walking an elephant in the hot sun in chains? Does the court’s compassion not apply to the goats that get sacrificed for Bakrid? Or is all religious practices equal, but some are more equal indeed?

How about the millions of chickens, cattle, pigs, etc, that get butchered and eaten for non-religious purposes? A few years ago, the Madras High Court decreed that the age-old sport of Jallikattu, the bull race, is cruel to animals and banned it. No doubt, no bull will be thrilled to be chased by a group of humans trying to hang on to their horns, and there could be no doubt that such acts do amount to a degree of cruelty. But if I am a bull with some degree of common sense, and I am left with the choice of being chased by eccentrically foolhardy men trying to hang on my horns or tail for a few seconds against being butchered, barbecued and eaten, I would prefer the former.

To my limited bull sense, running around with dangling humans from my horns beats being fried in oil and gobbled up with parrotta. To add insult to injury, when the voices of those who supported Jallikattu grew louder, the ban was revoked, and this became an essential traditional practice once again. The result is that now, as a bull, I have the privilege of being ridden on my horns, whipped as a beast of burden, being made to walk (not just stand) in the sun carrying a yoke and till the land, and being finally butchered and eaten too. As a bull, I reserve the right to call the bullshit on this selective human compassion that bleeds only for elephants standing in the sun and not for any other beasts, fowl or fish. All lives are equal, but some are more equal indeed.

Such judgements and directives come as a part of the activism and headline-hogging tendencies of individuals in power. They often get modified, forgotten or ignored when there is a collective pushback from more powerful groups, as seen by the Jallikattu issue or in the blatant animal sacrifices done in many temples and during religious festivals. Votebanks dictate our flow of compassion, framing of law and activism.

For now, we are bemused by the sight of forest officials roaming around in the temple festival grounds of central Kerala with a measuring tape to ensure the prescribed distance norms between the elephants. The famed Thrissur Puram is a few months away. In all probability, this new directive would get modified or ignored before the same as it is an emotional issue that can change the course of Kerala elections. Last year’s messing up of the age-old festival due to excessive police activism created a tectonic shift in Lok Sabha results. So it is a matter of time, before the poor elephants return to their miserable life.

That being said, temples need to seriously consider retiring the elephant and using alternatives to conduct the festival. Hinduism has always been a flexible religion, and it shouldn’t lose its sense of compassion in competitive religious fervour and whatabouttery. The fact that such judicial activism is targeted towards softer targets shouldn’t be the reason for correcting mistakes, no matter how old they are.

A substantial section of Hinduism, perhaps due to the influence of Buddha’s and Mahavira’s compassion, had turned to vegetarianism centuries ago, and most of the central Kerala temples where elephant parades occur follow these tenets strictly. It shouldn’t be challenging to extend the same compassion to these poor giants in chains without being lectured from the hoary high table of the judiciary.

Kerala temples can take a leaf out of chariot festivals in other parts of South India instead of chained elephants, or perhaps popularise the alternative of robotic elephants for parades that some temples have already started using. So many traditions have changed, and leaving these gentle beasts alone would be more faithful to the tenets of the branch of Hinduism these temples profess.

mail@asura.co.in

Anand Neelakantan

Author of Asura, Ajaya series, Vanara and Bahubali trilogy