No caste without Jati, Varna, Dvija and Adhama

We cannot talk about Hinduism without caste. When we say caste, we are using a European word. The local words are jati and varna. Jati refers to a community, and varna refers to a classification system which determines which jati is ‘high and pure’ (dvija) and which is ‘low and impure’ (adhama). There are 2,000 jatis, but only four varnas. The varna idea is far more recent than jati.

A jati is based on the roti-beti system. Only members of a jati can share roti (bread/vocation). Only members of a jati can marry a beti (daughter). These two simple rules created the vast number of castes across India over 2,000 years. While many trace this system to the Vedas, which are over 3,000 years old, recent genetic studies have revealed endogamy became the norm only 2,000 years ago. Prior to this period genetic mixing was widespread.

The Vedas, composed 3,000 years ago, are ambiguous about caste ideas. In fact, the earliest hymn that suggests a division of society refers to three categories, not four. These are the Brahmins, who compose poetry; the Kshatriyas, who defend the community; and the Vishaya, who take care of the cows. We know this from Rigvedic hymn 8.35, addressed to the Ashwins. In this context, the poets who compose hymns to the gods are distinguished from the fighters who wield weapons and the general populace who care for the cattle, indicating a pastoral society.

Later, in the Yajurveda, we are told that Vaishyas are born of the Rigveda, Kshatriyas from the Yajurveda, and Brahmins from the Samaveda. The Samaveda recounts the story of three boys raised by hymns, each of whom receives a boon. The eldest wants to be a Kshatriya and hold power, the second aspires to be a Brahmana and possess language, while the third, the Vishaya, asks for cows. Between the Rigveda, the Yajurveda, and the Samaveda, dated to 1000 BC, we see three groups of Aryas, with no particular hierarchy established between them. In Aranyaka texts, dated to 700 BC, there are ritual competitions in Mahavrata rituals between Aryas and Shudras, indicating Shudras were seen as outsiders.

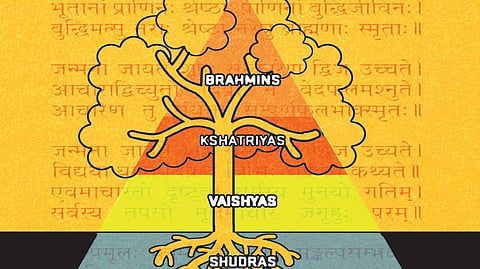

However, most curiously, in the 10th Mandala of the Rigveda, in the Purusha Shukta hymn, we are told that the primal being is quartered: from his head come the Brahmins, from his arms the Kshatriyas, from his trunk and thighs the Vaishyas, and from his feet the Shudras. This establishes a hierarchy of four groups of people. Where did this fourth category come from? Interestingly, this is the only time the word Shudra appears in the Rigveda. This has led to speculation that this particular verse was added much later to legitimise the four-fold varna system that was popularised by the Dharma-sutras and Dharma-shastras composed after 300 BC.

The oldest Dharma-sutra, dated to 300 BC, does not use the term dvija or twice-born. However, by 100 AD, the Dharma-shastra uses the term dvija to describe the Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas. Kshatriyas controlled land. Vaishyas controlled markets and trade routes. Both were patrons of the Brahmins. The fourth group, too poor to patronise a Brahmin yagna ceremony, was deemed Shudra, unworthy of the second birth that allows a member to hear the Vedic chant. A more popular term was adhama jati, or those communities that were deemed to be lower, inferior, and less pure.

Manusmriti explains that originally the creator, Brahma, established only four groups. But they intermarried and so hundreds of ‘contaminated’ jatis arose. But in all probability, the jatis have always existed in India, emerging from old tribal communities. The gated and walled communities of 4,500-year-old Harappan cities look very much like the ‘pols’ of Gujarat cities. This suggests segregation of communities involved in one vocation is perhaps pre-Vedic. The Brahmins categorised these many jatis, and created the varna classification system, to position themselves on top, and then creating the dvija category for their patrons.

Outside the dvija, were the Shudras (service-providers, servants, slaves), the Chandala (crematorium keeper), the avarna (outcaste), the mleccha (barbarian), the nishadha (tribal). The upper and lower end of the Brahmanical four-fold varna system is clear: the pure Brahmin above and the impure Chandala below. But the position in between is confusing. Where do you locate the Kayastha, or influential scribe community, as dvija or adhama? The Rajputs were called Kshatriyas but the Marathas were denied this status even in the early 20th century.

Now we have a neo-varna system: General Category (GC), Other Backward Communities (OBC), Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST). Earlier everyone wanted to be the higher varna, the dvija, and get the privileges from royal courts. Now, in a secular democracy, more and more communities want to lower their neo-varna status and get benefits of reservation and positive discrimination. This flexibility is only found in the middle, not available to the Brahmin anymore.

Devdutt Pattanaik

Author and TED speaker

Posts on X: @devduttmyth