Important to question government’s motivation behind Agnipath Scheme

The Agnipath scheme has once again returned to the centre of controversy, with the opposition taking it up vociferously in the parliament.The employment situation in India is getting grimmer by the day despite the economic boom. In many economically backward states, the defence forces have been one of the biggest employers. When this door is getting closed, it is natural to see resentment among the youth.

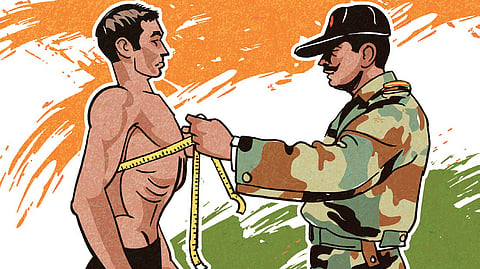

The Agnipath scheme, launched in June 2022, recruits youth called Agniveers for four years. Afterwards, only 25 per cent are retained, and the rest are left without support. The hope is that their training in the defence forces will make them employable in the job market.

There has been a debate over this scheme. The opposition raised the issue of pay disparity and compensation for Agniveer soldiers compared to regular soldiers. This raises concerns about different rules for soldiers fighting together and potential impacts on unit cohesiveness. Regular soldiers receive years of training, while Agniveer soldiers only get six months, which many former defence officers have questioned.

In an interview with renowned journalist Karan Thapar, Admiral Arun Prakash, former Navy chief stated, “It must be recognised that at least five to six years are required before a new entrant can acquire hands-on experience to be entrusted with the operation or maintenance of lethal weapon systems and complex machinery and electronics.”

As experts debate the benefits of this military scheme, it’s important to question the government’s motivation behind it.

The Agnipath scheme aims to reduce pension payouts and allocate more funds towards defence investments and modernisation. By providing a fraction of the regular pay, and no pension liability, the scheme targets financial benefits rather than other justifications.

The question is whether we can afford to compromise on our national security for financial considerations. The assumption that the forces could maintain their current operational efficiency with significantly less experienced personnel is dubious at best. It’s like expecting a car to run with the same performance after replacing its core components with cheaper, substandard parts. The danger inherent in such a gamble is clear.

While cost-cutting may be an essential aspect of any government regime, it is also crucial to balance fiscal prudence against national security interests. This becomes especially relevant in the face of rising global political instabilities and unpredictable trends in international warfare. A military force that is not adequately prepared for the demands of modern combat scenarios is a liability, not an asset.

A few critics also argue that the Agnipath scheme could potentially create a divide among the ranks, resulting in decreased morale and erosion of unity within the troops.

Years ago, India was struggling with poverty and food shortages. The country had recently lost its flamboyant Prime Minister and suffered a defeat at the hands of China. A humble man was now in charge, facing both a famine and a war.

Under Lal Bahadur Shastri’s leadership, India’s army grew strong enough to defeat Pakistan in just seven years. Additionally, our farmers successfully made the country self-sufficient in food, despite a five-fold increase in population.

Now, India is a powerful country, or so we say. We are about to become the fourth richest nation by GDP soon. Our infrastructure is booming and we are building gigantic statues and bullet trains that all of us are proud of.

We are proud of taking good care of many government servants. There are around 16 lakh pensioners in Railways, a department known for its gross inefficiency, paid from our tax money. There are approximately 4 lakh telecom and 3 lakh postal department pensioners, again supported by our tax money.

Numerous state and central administrations have so many babus who have vowed to make our lives easier and we pay them salaries and life-long pensions far higher than the average income of Indians. We have enough, and more, money for maintaining the power and pelf of Indian Administrative Services. We have no issues with resource draining central and state PSUs that have been in red for decades. What are our taxes for if not to feed all these departments? However, what baffles us is that none of these departments have anything similar to the Agnipath scheme. Is it that the bureaucratic tasks like pushing pens and scrolling through files require permanent employees with high salaries and life-long pensions, while young men, who are called to put their lives on the line, deserve only temporary employment at a lower pay?

When we were a poor and broken country, we had prioritised the kisan and the jawan. Now, we claim to be a super power, but we have no money for either the farmer or the soldier.

If a country cannot find sufficient budget for maintaining its armed forces and giving pensions for the soldiers who risk their lives for the protection of the nation, then the priorities of that country certainly need to be questioned. If budget is the priority, why not extend the Agnipath scheme to all government departments and PSUs, and offer only temporary employment of four years? That way we can employ all Indians on a rotation basis and solve the employment problems too.

Anand Neelakantan

Author of Asura, Ajaya series, Vanara and Bahubali trilogy

mail@asura.co.in