Delhi’s pollution crisis needs evidence-based policy reform

The capital of the world’s largest democracy—Delhi—is grappling with a pollution crisis. With approximately 80 per cent of Delhi’s waste being generated by only about 20 per cent of the people, the city is finding itself in an increasingly challenging situation.

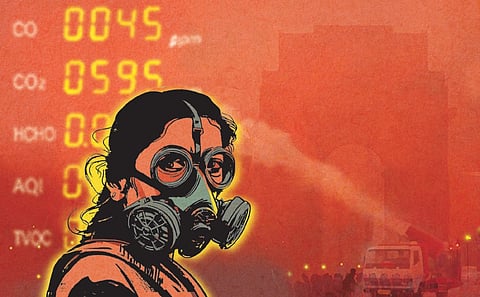

Simultaneously, the air quality in Delhi has reached alarming levels, with the people of Delhi breathing in PM 2.5 almost 30 times higher than the WHO standard. Coupled with this, the Yamuna river, once a vital water source, now runs filled with toxins and heavy metals.

The initiatives by the Delhi government to combat pollution are lacking in both necessary vigour and scientific rigour. Several of the current initiatives fail to meet established standards or do not seem well-researched. For instance, the mechanised sweeping vans frequently seen on Delhi roads are largely ineffective due to several factors: uneven road surfaces, their inability to sweep the dust off the full width of the road, and limited daily coverage. Machines procured from a foreign country at the cost of crores of rupees cannot work in the Indian context unless specifically tailor-made for our needs.

Anti-smog guns, a prominent feature of Delhi’s winter pollution control efforts, are unsustainable. These machines consume lakhs of litres of water daily, worsening the city’s ongoing water shortages. Further, while Delhi government’s guidelines advise against using treated sewage water at active work zones and construction sites, several reports indicate that treated sewage water is often used for sprinkling in Delhi, which could result in additional health problems.

The issue of pollution in the Yamuna is dire, with several sections now declared ecologically dead. Recently, ahead of the Chhath celebrations, the Delhi government resorted to spraying chemicals into the river to mitigate the toxic foam that has become a recurring problem. While officials claim these chemicals are food-grade and safe for public health, one must question why such measures are not implemented year-round. Despite numerous promises—many of which date back over a decade—and significant funding from the central government, the situation remains unchanged.

Solid Waste (Mis)Management

A few years back, the Supreme Court criticised the solid waste management in Delhi. It highlighted that about 3,800 tonne per day of solid waste remained untreated, which ultimately reached landfills. In 2022, the AAP took over the reins of the unified MCD with a bold promise—it would make Delhi garbage-free.

The Bhalswa landfill was to be cleared by June 2022, Okhla by December 2023 and Ghazipur by December 2024. The reality is much different. The city’s population is expected to rise to 2.85 crore by 2031, and along with it will rise the daily generation of waste. Without effective policy measures, there is no hope.

Waste management strategies must target major contributors, implementing measures such as stricter regulations, incentivising recycling, overhauling solid waste treatment, and promoting sustainable practices.

The Impact of Pollution

A study conducted by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC) revealed a shocking statistic: every resident of Delhi is losing an average of 11.9 years of life due to air pollution. This alarming finding should serve as a wake-up call for policymakers and citizens alike.

Moreover, the Economic Survey of Delhi indicates that approximately 40 per cent of the population is exposed to TB germs and is vulnerable to the disease. The incidences of TB in Delhi are 175 per cent higher than the national average, while TB related mortalities in Delhi are the national average. The link between environmental degradation and public health cannot be overstated; as pollution levels rise, so do the risks of communicable diseases and chronic health conditions.

Policy Failures and Inaction

Despite numerous schemes announced by the Delhi government aimed at tackling toxic air, many remain unimplemented. These include using drones to map bad air sources and making PUC certificates compulsory to buy fuel, conducting workshops on ‘urban farming’, and developing 17 “world class” city forests. While some of these are stuck in various stages of the tender process, others are yet to be notified. Further, the numerous promises made by former chief minister, Arvind Kejriwal, regarding the Yamuna river should also come under scrutiny.

To effectively address pollution in Delhi, there is an urgent need for policies grounded in scientific research and data-driven decision-making. Establishing robust mechanisms for data collection on pollution levels, regular monitoring to identify trends, and timely assessment of the effectiveness of policy interventions should guide future policy decisions. As residents advocate for change, it is imperative that government officials respond with actionable plans rather than empty promises.

Sumeet Bhasin

Director, Public Policy Research Centre

Posts on X: @sumeetbhasin