The Supreme Court of India stood out in 2018 for several landmark verdicts which included decriminalising homosexuality (certain provisions of 377 were struck down), decriminalising adultery and allowing women's entry into Sabarimala.

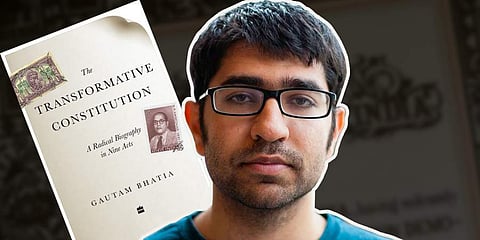

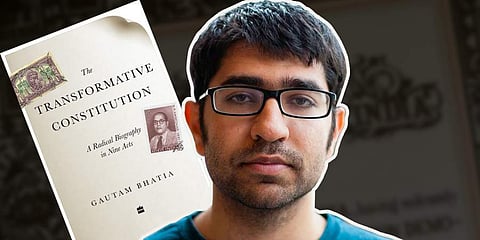

Although, these verdicts touched upon the "transformative" part of the Constitution, advocate and author Gautam Bhatia argues not only colonial laws, but also post-independence laws that conflict with fundamental rights need to be revoked.

In his book "the Transformative Constitution", Bhatia contends that contrary to conventional wisdom the Constitution is an evolving document which must evolve constantly to keep pace with the times. Bhatia, a strong critic of Aadhaar, explores the principle of equality, fraternity and liberty through nine "radical" judgments.

In an exclusive interview, he speaks about Aadhaar, Supreme Court, sedition and women's participation in the legal system.

Would you like to elaborate for our readers what you mean by the term "Transformative Constitution"?

By a “Transformative Constitution”, I mean a Constitution that set out to transform not merely the political structure (by transferring political power from an alien, colonial regime to an elected government of the people), but also to transform oppressive social practices centred around caste, gender, and religion. A Constitution that set out also to democratise the relationships between individuals and social groups, as well as between individuals themselves.

You have reiterated that the Courts over the last seven decades have failed on multiple occasions to fulfil the Constitution’s “transformative promise”. Will you say that in the wake of recent landmark judgements things are getting better?

Some recent judgments – such as Section 377, the decriminalisation of adultery, and the Sabarimala judgment – that specifically invoke transformative constitutionalism – give cause to hope. At the same time, judgments such as Aadhaar, or the recent proliferation of “sealed covers” in high-stakes cases, suggest more of the same old story.

In your book you wrote, “The Constitution is treated as an evolving document, with judges bearing the responsibility of updating it”. Are you happy with the interventions? What more can be done in your opinion?

It’s important to note that the “updation” I’m talking about is not about judges applying their own personal sense of right or wrong, or contemporary morals; the “updation” refers to excavating the core values of the Constitution and applying them to an always-changing world. For example, the Constitution is committed to pluralism and tolerance for different ways of life, values that stem from Articles 14 (equality), 15 (non-discrimination), and so on. When you understand these underlying values, it is easy to see how criminalising same-sex relations violate the guarantees of equality and non-discrimination, as understood in the light of these values. So, even though the Constitution makes no specific mention of sexual orientation - because the issue simply wasn’t in the mind of the framers - the Court can legitimately hold that criminalising same-sex relations is ruled out by the Constitution.

You have also documented the need to repeal colonial laws that contravene with fundamental rights. Parts of Section 377 have now been struck down. What other colonial-era relics should be repealed and why?

The issue is not only colonial laws, but also post-independence laws that have been framed directly along the lines of colonial laws. The most glaring example of this – which I discuss in the book – is national security legislation such as the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), the National Security Act (NSA), the Goonda Acts, and so on. These laws heavily stack the deck against an accused individual, and guarantee that they will spend long years in jail before their trial is even completed.

You have been critical about article 19(2) in your book. Will you say that the Narendra Modi government has abused the Sedition law?

Every government has abused the law of sedition, something that has been enabled by the Supreme Court choosing to uphold it in 1962.

As Aadhaar raises questions on state surveillance, how safe are we as digital citizens?

In the absence of strong data protection legislation – a lacuna that the Supreme Court has pointed out on more than one occasion – we remain vulnerable both to State surveillance, as well as commercial exploitation of data.

At present, what pending/ ongoing cases are you looking forward to?

Recently, a case was filed challenging the provision of the “restitution of conjugal rights”, which is something I’ve discussed at length in the book, while talking about democratising family relations. It will be interesting to see if the Court reconsiders its original judgment from 1983 that upheld it. There’s also an ongoing case in the Hyderabad High Court against the large-scale deletion of voters from the electoral rolls, by using Aadhaar. Among other things, it demands that the software used for these deletions be made public. This is a very crucial case for the future of our democracy, and I’m watching it keenly.

The DNA Technology (Use and Application) Regulation Bill, introduced in January 2018, failed to get the Parliament’s nod. It has been criticised for posing a potential threat to privacy and security, how do you read it?

It’s a huge threat to privacy – as well as equality because DNA databases have been documented to have an adverse effect on the most vulnerable populations – and I discuss why in the Epilogue of the book. It allows for widespread DNA collection and storage in a disproportionate manner and lacks adequate safeguards. A “dissenting note” by Usha Ramanathan, who was on a Committee of Experts that discussed the bill, sums up many of the problems with it.

As per a report, only 9 per cent of the High Court judges are women. What do you think led to such gender disparity and what is the need of the hour to fix it?

The legal profession is institutionally hostile towards women. This is not simply a function of the widespread sexism at the bar – which, unfortunately, exists beyond a shadow of doubt – but also a function of structural issues. For example, I have colleagues who need to travel long distances between home and office, and also have to do very long and late working hours. In a city like Delhi, there are serious concerns about physical safety in situations of this kind. But there’s pressure upon you not to go home early, for fear of missing out on important matters at the office – an absolute Catch-22 situation. Examples of this kind abound, and create an environment where it is significantly more difficult for women to succeed than it is for men.

You obviously need to fix an institutional problem by taking institutional measures, but that requires a large-scale overhaul of the workings of the profession. That can only be achieved incrementally, and through spreading awareness; in the meantime, I think there need to be more effective remedies, such as ensuring adequate representation of women on the bench, in terms of numbers.

Title: The Transformative Constitution: A Radical Biography in Nine Acts

Author: Gautam Bhatia

Publisher: HarperCollins India

Price: Rs 699