Abhijit at the age of twelve, like many of his friends, was in love with Audrey Hepburn. He discovered her as Eliza Doolittle in the movie version of the Lerner and Loewe musical My Fair Lady, based on the play Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw (a radical left-winger in his time). In the play her father, Alfred, makes this truly wonderful little philosophical speech (before more or less offering to sell his daughter for five pounds even):

I ask you, what am I? I'm one of the undeserving poor: that's what I am. Think of what that means to a man. It means that he's up against middle class morality all the time. If there's anything going, and I put in for a bit of it, it's always the same story: "You're undeserving; so you can't have it." But my needs is as great as the most deserving widow's that ever got money out of six different charities in one week for the death of the same husband. I don't need less than a deserving man: I need more. I don't eat less hearty than him; and I drink a lot more. I want a bit of amusement, cause I'm a thinking man. I want cheerfulness and a song and a band when I feel low. Well, they charge me just the same for everything as they charge the deserving. What is middle class morality? Just an excuse for never giving me anything.

It was hard being poor in Victorian England where the play is set. To be deserving of charity one had to be abstemious, thrifty, church-going, and above all hard working. If not, it was off to the poorhouse where work was enforced and husbands and wives were kept apart, unless you happened to be in debt, in which case it was to debtor's prison or an enforced trip Down Under. An 1898 "map descriptive of London Poverty" classified some areas as "lowest class, vicious, semi-criminal."

We are not very far from this today. Mention welfare in a well-heeled crowd in the United States, India, or Europe and there will always be a few shaking heads, worried that welfare turns the poor into "good for nothings", to use a Victorian expression still popular among a certain class of Indians. Give them cash and they will stop working or drink it up. Somewhere behind this is the suspicion the poor are poor because they lack the will to achieve; give them any excuse and they will check out...

...In India, the government is now considering moving to what it calls direct benefit transfers, sending money to people's bank accounts rather than giving them food (or other material benefits), on the grounds that it would be much cheaper and less subject to corruption. However, there is considerable opposition, led mostly by left-wing intellectuals. One of them interviewed twelve hundred households throughout India about their preferences for cash versus food. Overall two-thirds of the households preferred food transfers to cash.

In states where the food distribution system worked well (mainly in South India), this preference was even stronger. When asked why, 13 percent of households mentioned transaction costs (the bank and market are far, so it's hard to turn cash into food). But one-third of the households who prefer food argued that getting foodstuff protects them against the temptation to misuse cash. In Dharmapuri in Tamil Nadu, one respondent said, "Food is much safer. Money gets spent easily." Another said, "Even if you give ten times the amount I will prefer the ration shop since the goods cannot be frittered away."

And yet there is nothing in the data to suggest they are right to be so worried. As of 2014, 119 developing countries had implemented some kind of unconditional cash assistance program and 52 countries had conditional cash transfer programs for poor households. Together, one billion people in developing countries participated in at least one of these.

The initial phase of many of these programs was implemented as an experiment. What is very clear from all these experiments is that there is no support in the data for the view that the poor just blow the money on desires rather than needs. If anything, those who get these transfers raise the share of their total expenses that go to food (i.e., it is not just that they spend more on food when they have more money, but they might even spend so much more that the fraction of food spending goes up); nutrition improves and so does expenditure on schooling and health. There is also no evidence that cash transfers lead to greater spending on tobacco and alcohol. And cash transfers generally increase food expenditures as much as food rations.

Even men do not seem to waste the money; when the transfers are given at random to either a man or a woman, there is no difference in how much is spent on food versus, say, alcohol or tobacco. We are still in favor of giving the money to the woman, because it restores a little of the balance of power within the family and might allow her to do what she deems important (including working outside of the home), but not so much because we think that the man will drink it up.

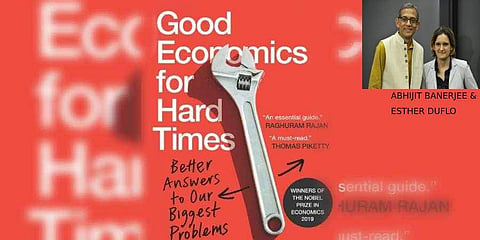

Excerpted from Good Economics for Hard Times: Better Answers to Our Biggest Problems, authored by Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee (winners of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences 2019), published by Juggernaut Books.