Migrants key to economy reboot

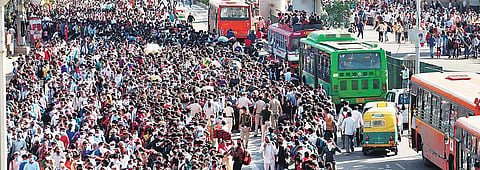

NEW DELHI: Anil Kumar worked as a daily wage worker in Delhi. Left with no work, food and water following the lockdown, he is among the estimated 1.1 million migrant workers sheltered in camps across the country. Facing an uncertain future, he wants to return to his home in Etah, Uttar Pradesh, and has vowed never to return to the city.

Rakesh was a stone cutter employed at one of the many construction sites in Delhi. After the lockdown, he was left to fend for himself, having lost his job and thrown out from his rented room. He, too, wants to go back home in Gonda, UP, and will not return.

Migrant workers like Anil and Rakesh make up 80 per cent of India’s workforce. The country’s infrastructure is built on their backs. Yet, the government’s relaxation of the lockdown’s stringent guidelines from April 20, aimed at restarting the economic engine, does not address the issue of the return of the migrant workers, most whom who have left for their villages.

Experts such as Chinmay Tumbe of the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, said the lack of transport could hamper the productivity of sectors such as agriculture, construction and manufacturing that will be opened up.

“Most of the sectors that have been granted relief have migrant workers as the majority workforce. The extended suspension of transport services is a constraint. I hope the government has a plan to ensure that migrant workers reach their workplaces to ensure that the sectors are up and running,” Tumbe said.

According to the International Monetary Fund, migrant workers comprise 97.1 per cent of the informal workforce in the agriculture sector, 74.5 per cent in construction and 22.7 per cent in manufacturing. The figures underline their importance in setting the wheels of the economy in motion.

A research scholar at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences echoed Tumbe’s view. “If you see the data, the informal workforce in agriculture alone adds around 17 per cent to the economy. So merely by granting relief in guidelines, the sector is unlikely to prosper,” she said.

The need of the hour is to get the workforce to their respective workplaces, she said, adding that “it is high time that the government chalks out and executes a plan to run special transport services for migrant workers.”

A field officer at SHRAM, an NGO working for the welfare of migrant workers, was of the view that getting the workers to their workplaces would help boost their mindset. “Over the past two weeks, these workers have been out of work and with no pay leading to immense psychological stress among them. Once they start working, they will be able to earn again and send remittances home, thus bringing down the agitation levels in their minds,” she said.