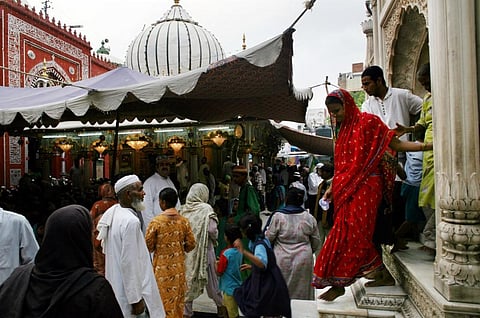

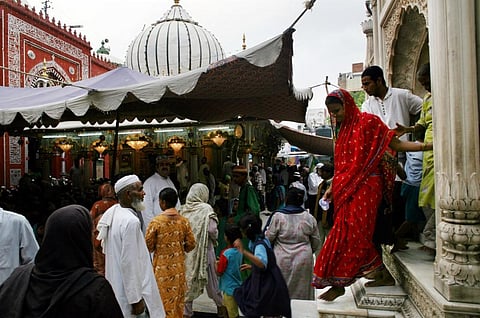

Perhaps, for the first time in over 70 years, more khwaja ke ghar rang hai ri won't reverberate in the courtyard of Delhi's Hazrat Nizamuddin Dargah to celebrate the 716th Urs (death anniversary) of Amir Khusrau, who rests next to his beloved peer.

The lanes of Nizamuddin Basti that lead to the Dargah won't be filled with the intoxicating scent of incense and sandal. Neither will the tombs be lit up with lights and laughter, nor will the qawwals sit in a circle repeating the glorious words that Khusrau left for the world to cherish.

The Urs is among the several things that the pandemic has robbed from humanity this year. The Dargah which used to witness a sea of devotees across religious spectrum celebrate Khusrau and his Mehboob-e-Ilahi, now wears a gloomy silence, almost as if it's grieving for a lost love.

"The Urs is being held from June 9-13 and there won't be celebrations this year given the current situation. A few members of the dargah committee will offer prayers inside the mosque. We are praying for the health of everyone," said Syed Aziz Nizami, the administrator.

The celebratory langar which was started by Saint Nizamuddin Auliya in the 14th century has been called off as well.

It is rather alluring how the death anniversary of a Sufi saint is not mourned but celebrated. Urs in Arabic means "wedding" which symbolises the union of the lover with the beloved (often the union with God).

Khusrau couldn't be buried with his peer Nizamuddin Auliya, so he lies in a tomb next to him and the Urs is a celebration of their union. The Sufi is said to have blessed the world with Qawwali, at the centre of which lies Zikr or remembrance of God. The Qawwali, a part of traditional Mehfil-e-Sama, is a Chishtia Sufi practice to invoke the glory of a peer. And Khusrau turned it into a vehicle for communicating his love for his peer, Nizamuddin.

"Devoted to a Sufi who disliked emperors, he himself made his living by serving in their courts. It was a shrewd balance of sense and sensibility: day job in the court, evening spirituality in the shrine," writes Mayank Austen Soofi, chronicler of Delhi.

So indestructible was his love for his peer that after Nizamuddin passed away in 1325, Khusrau left everything behind and surrendered himself at Nizamuddin's tomb. He wept During that time he wrote:

"Gori sovay sej par, mukh par daarey kes,

Chal Khusrau ghar aapnay, saanjh bhayee chahu des."

(The fair maiden rests on the wreath, her face covered with tresses

Oh Khusrau, let us go home, the dusk settles in four corners)

The subcontinent owes a lot to this 13th-century Sufi -- Hazrat Amir Khusrau -- known as the original poet of the people and who was remarkable for bringing forth a linguistic and cultural synthesis. The mystic mingled Persian and Hindavi (a mixture of Khari Boli, Braj Bhasha, Awadhi dialect) and went on to write 92 odd books in the new language called Khaliq Bari.

"Khusrau darya prem ka, ulti waa ki dhaar

Jo utra so doob gaya, jo doba so paar."

(Oh Khusrau, the river of love runs in strange directions.

One who jumps drowns, and one who drowns, gets across)

"Khusrau is one of the most transformative and influential figures in the cultural history of northern India -- a history that is also tied to the other parts of the subcontinent like the Deccan. He epitomises the coming together of the genius of the South Asian and Central Asian creative process, it was in his persona that the diverse streams of the two worlds came together like never before," writes Saif Mahmood in his book Beloved Delhi.

A polyglot, poet, musicologist, composer, Khusrau has been touted as a poet whose writing offered a secular way of thinking and living. Being a Muslim, he often wrote and sang songs on Hindu devotional themes.

Born to a Turk father and Rajput mother, the Dilliwala called himself Turk-e-Hindustani while his peer Nizamuddin Auliya called him Tooti-e-Hindustan, (parrot of Hindustan).

In his Hasht-Bihisht (Eight Paradises), he narrates a dialogue between a Muslim Haji going to Mecca and a Brahmin on his pilgrimage to Somnath, where he insists on religious tolerance.

Although Khusrau is remembered as one of the greatest symbols of cultural pluralism, it's his resting place that was demonised by the right-wing and a section of the media earlier this year.

Amid the coronavirus pandemic, a Tablighi Jamaat event was held in early March, which was attended by foreign delegates who turned out to be COVID-19 carriers. Once the news gained traction, Nizamuddin Basti was sealed and the Jaamatis, who had returned to their respective home state were hounded for days. Soon, the incident was painted with all shades of communal colour.

The Urs might have fallen silent this year, but it's shameful that we as a country must let a Markaz overshadow the brilliance of Khusrau.