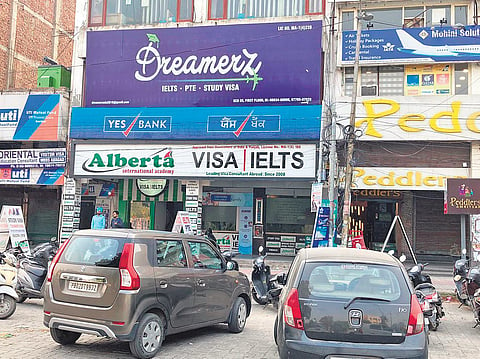

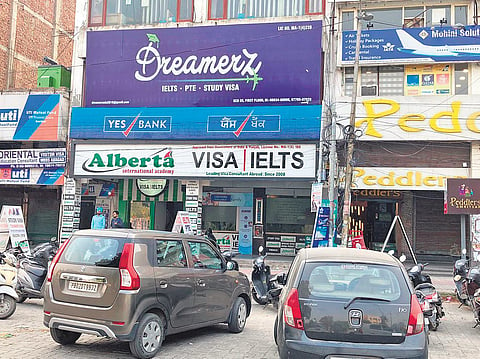

All of Punjab’s eyes may be fixated on the high-octane contest in Amritsar East constituency, where two political giants, Navjot Singh Sidhu of the Congress and Bikram Singh Majithia of the Akali Dal, are pitted against each other, but it is a big yawn for Sallupreet Kaur, 22, a college student who has enrolled herself in one of the many International English Language Testing System academies in Amritsar.

“I don’t know where Amritsar East is and I don’t care, all politicians are thieves. All I know is I have to clear the IELTS to go to Canada,” she said as she took out a black dupatta from a cabinet of the scooty, wrapped her face with it, revealing only her eyes, before starting on a dust-ridden ride to her home about 6km away.

Arti Kaushal, 24, an IELTS coordinator at Sky Bridge Academy in the heart of Bathinda, also had similar dreams to fly away abroad, but it crash landed as her parents had matrimonial plans for her. “I had cleared my IELTS from this academy itself but now I now work here, maybe someday I will also migrate,” she said in hope.

Kaur and Kaushal are among the lakhs of youth for whom politics and the ongoing elections are of least interest. With little job avenues in the state, particularly for the educated, coupled with the tentacles of drugs that lurk from every quarter, most of the youth, urban and rural alike, harbour dreams of going abroad to escape the double-fisted punch of berozgari (unemployment) and nasha (drugs).

For Gurpreet Singh, 20, a second year college student in Abohar town of Fazilka close to the Pakistan border, politicians are the devil-incarnate. “In the last five years only a few roads have come up in this town but there are no jobs here, all the leaders are useless. After college I plan to go to Australia,” he said, his language often laced with expletives.

The 2011 Census put Punjab’s population at 2.77 crore, of whom about 60 lakh are in the 18-30 age bracket. This huge mass could have potentially constituted the much-touted demographic dividend but a large number desires to go abroad lest they turn into social pariahs.

According to the Punjab Ghar Ghar Rozgar & Karobar Mission under the state’s Department of Employment Generation, more than 13.48 lakh had registered with the mission’s websites for employment, but there were only 7,561 government jobs available, 4,126 in the private sector.

While the economically better-placed youth aim to leave the country, the poorer sections pick up vocations after dropping out of school. Gursevak Singh, 25, of Ramdas town in rural Amritsar, had hoped to get a class IV job in the government after finishing “plus two,” but luck was not on his side. He then trained to become a barber and now runs a sparsely equipped, single-seater salon from a garage-type shop taken on rent. “Before Captain (Amarinder Singh) became the CM in 2017 he had promised one job for each family. Had he kept his promise I wouldn’t have become a barber, I barely manage to earn enough,” he rued.

Like Gursevak, Surinder Singh, 30, a combine harvester mechanic in Dhaula village, Barnala, also left school as his family could not fund his education anymore. “Parties like the Congress, Akali Dal and the BJP need to be thrown out or there will be no employment. I had to leave school to feed my family,” he said.

As in 2017, all parties have made a slew of job promises this year also. While the Congress has vowed to generate one lakh jobs every year, the Akali Dal and the Amarinder-BJP combine have announced 75% quota for the state’s youth in private jobs. But, Raja Singh, 24, an unemployed youth in Gumrah, a

village deep into rural Amritsar, is both cynical and hopeful. “If they had kept even half the promises they mad then the drug problem would not have been so bad. It has been a story of betrayal so let’s see,” he said, his village largely untouched by the election fervour elsewhere.

H Khogen Singh @ Bathinda/Barnala/Amritsar (Punjab)