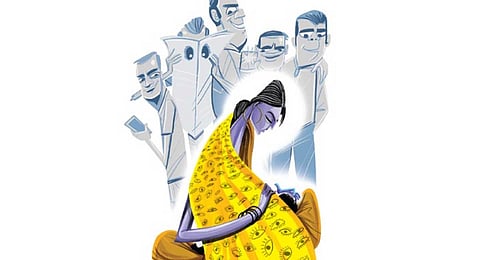

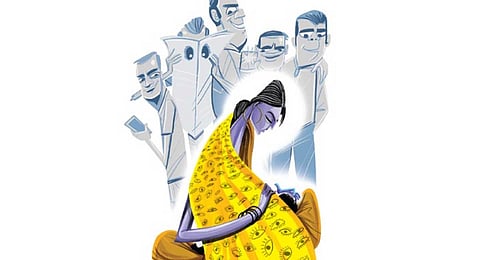

NEW DELHI: Breastfeeding is essential for both mother and infant, but many urban women in India struggle with stigma and discomfort when doing it in public spaces, a latest study has found.

The study, published in Preventive Medicine: Research and Reviews, said the main challenge was the sexualization of breasts in urban India, which led to feelings of discomfort, shame, and fear of judgment.

“The study found that breastfeeding in public is not a natural or comfortable experience for many urban women. It is something they must carefully plan, negotiate, and emotionally manage,” Dr Nupur Bidla, the principal author of the study, told this paper.

The study found that urban Indian women want to breastfeed anytime, anywhere, which does not necessarily require an assigned space.

“But she wants a healthy, normalised environment and people around that do not make the woman feel judged,” said Dr Bidla, who is also Central Coordinator of Breastfeeding Promotion Network of India (BPNI), a 32-year-old organisation working to promote exclusive breastfeeding in the country.

Highlighting the importance of incorporating breastfeeding counselling for women, the study said that social, cultural, and psychological barriers can be addressed at an early stage to empower women and their partners to overcome inhibitions related to public breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding is the most beneficial form of infant nutrition in the first year of life. Yet in India, despite 88.6% institutional births, only 41.8% initiate breastfeeding and 63.7% exclusively breastfeed. This has improved over the years, but remains low.

The study stressed that unless breastfeeding, considered to be a preventive strategy against child morbidity and mortality, does not become socially acceptable across settings, its full protective potential cannot be realised.

“This qualitative study shows that breastfeeding in public is far from a natural or comfortable experience for many urban women. Instead, it involves constant planning, emotional labour, and coping strategies - using dupattas as covers, choosing discreet seating, feeding before stepping out, or organising daily routines around feeding schedules or avoiding going out of the house,” she said.

She said there is an urgent need for a mindset change - to normalise breastfeeding in public as a natural and essential act - so that women no longer have to adapt themselves to hostile spaces, but are supported by society, policy, and infrastructure.

“What often goes unnoticed is the emotional and mental labour women perform while breastfeeding in public, constantly anticipating reactions and adjusting their behaviour,” Dr Bidla added.

The study found that in India, many women grow up with the belief that public spaces, especially those with male presence, are unsafe, leading to internalised fears around public conduct and bodily exposure.

“While most women initially felt hesitant or fearful about breastfeeding in public, concerns about their child’s health and support from family, especially partners and elders, often helped them overcome these inhibitions,” the study added.

The authors surveyed 40 urban women, aged 26-39, in the national capital who breastfed in public (their children ranged from 3 months to 5 years).

Of the 32, eight were first-time mothers, and 24 were second-time mothers. While 21 had regular deliveries, nineteen underwent caesarean deliveries.

Twelve women initiated breastfeeding within the crucial one hour of birth, aligning with global recommendations, while five initiated after two hours. Thirteen mothers initiated breastfeeding within 24 hours, and ten began only after 24 hours, indicating delays that may be linked to hospital practices or lack of support.

Twenty-five were working mothers, seven were homemakers, and eight had quit their jobs for child-rearing responsibilities.

The study said that despite government promotion of breastfeeding, women commonly limit outings during breastfeeding months due to discomfort, fear of sexualization, or past negative experiences like harassment.

Clothing played a key role in shaping public perceptions of breastfeeding. Dupattas, covers, and specially designed outfits offered women a sense of modesty and social acceptance.

In contrast, traditional or tight outfits (such as lehengas) made feeding more challenging.

In urban settings such as malls, women and their partners often search online for breastfeeding-friendly facilities.

When unavailable, they resorted to changing rooms or secluded corners.

Traditional markets sometimes offered informal support through accommodating shopkeepers.

Cars were often used as private, mobile spaces for feeding, though some women reported feeling exposed when parked in crowded areas.

The study highlighted that husbands played a supportive role, accompanying their wives, shielding them from unwanted attention, and helping normalise public breastfeeding.

“We found that metropolitan women navigate public breastfeeding challenges through social, emotional, and practical strategies. Recognising these coping mechanisms can help advocates, policymakers, and healthcare providers foster a more supportive environment,” Dr Bidla said.