Peacekeeping is not a job for soldiers but only soldiers can do it,” remarked Dag Hammarskjold, former secretary general of United Nations. In the past seven decades, a contribution of 2,40,000 troops and an ongoing presence of 6,200 Army personnel along with 150 military observers makes India one of the largest contributors to peacekeeping; of note is that 15 per cent of the military observers are women, a prime UN requirement. With the world commemorating 29 May as International Peacekeepers Day, it is time for a reality check of whether blue beret operations have contributed to New Delhi’s aims in world politics or are we only glorified flag bearers of altruism?

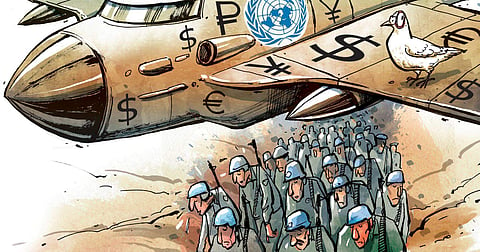

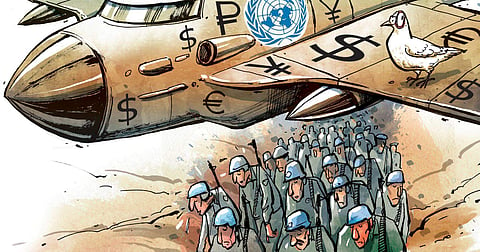

The UN is the most political of all world bodies. While the overt stance of every country is to further world peace, and fancy terms like R2P (Responsibility to Protect) keep getting generated, each nation drives its own agenda sub-surface. The P-5 countries wield enormous power due their monetary contribution; 22 per cent by the US and between 3 per cent and 5 per cent by Russia, UK and France.

Their personnel, accordingly, occupy pivotal decision making positions in the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) in New York and in peace keeping missions in the troubled regions. China, a late starter, has crept up the power ladder and contributes 7.92 per cent of the budget, presently has 3000 peacekeepers in UN missions and has pledged 8000 additional troops for deployment if an emergency arises.

Beijing has also contributed $100 million to the African Union for deployment of troops from the continent for its peacekeeping missions. This, however, is not all kosher; its economic interests lie in Africa and by influencing local leadership and different faction and clan leaders, it is pumping out oil and carting back timber and minerals from that continent.

Similarly, the contribution of P-5 members is agenda driven, with regime changes, business contracts et al being surreptitiously pursued—think Libya, Syria, Iraq! India’s contribution is only 0.737 per cent of the UN budget but it needs to take a leaf out of the strategy of the P-5 by building on the sacrifices and goodwill generated by Indian peacekeepers for enhanced politico-economic leverage on the world stage.

India has a total of six battalions in the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan and Lebanon, 250 troops in Golan Heights and has pledged engineering and signal companies to be moved at short notice when required by the UN.

Additionally, we have police contingents, including all women units, deployed for their specialist roles in peace missions. For a period of a decade there were 28 helicopters (equivalent of three helicopter units) in Sudan and Congo till their withdrawal in 2011 for internal anti-Naxal duties. Having been the assistant chief of air staff at Air HQ looking after UN ops, this writer is aware of the desperation that UN was driven-to as no other country was willing to send any costly rotary wing assets (UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon reportedly telephoned Dr Manmohan Singh for a re-think of New Delhi’s decision). Since the IAF has now acquired 80 new Mi-17 helicopters, with another 48 on order, these important mission enablers could be offered again. Should this, and the enormous ongoing Indian Army contribution, be a quid pro quo for something in return?

While the P-5 are loathe to commit their soldiers due to their high casualty aversion, we have lost 165 brave Indians to the cause of world peace. Since politics is not a place for philanthropy, due returns must accrue for India’s consistent contribution of human capital to peacekeeping.

The reality, however, is that at present there is no Indian Force Commander in the 15 ongoing peace missions and our representation of only five to six mid-level officers in DPKO is miniscule. India’s inputs in policy making and drafting of mission mandates has, thus, reduced considerably putting Indian lives in greater danger. This needs rectification since peace missions are seeing an increasing number of fatalities, as witnessed last year in Congo when 14 Tanzanian peace keepers lost their lives in a single rebel ambush; that this was not debated much by the world speaks for itself—imagine had they been peacekeepers from the P-5.

Additionally, India’s foreign policy initiatives and economic outreach must build on our impressive peacekeeping credentials. The Asia-Africa Growth Corridor could do well by building on the goodwill in Africa for Indian soldiers. As commander of the IAF mission in Sudan this writer was witness to how the word Inde would remove all inhibitions among locals, who otherwise consider the UN suspect.

This soft power asset must translate to the next step of enhanced economic engagement, which has lost out to others, especially China. For example, Mahindra Scorpio vehicles taken by our contingent competed on an equal footing with the Toyotas and Mitsubishis that populate UN inventory. So, how about Indian automotive firms pitching for local and UN contracts? Why not send ALH Dhruv helicopters and showcase them for markets? Sudan has one of the world’s largest livestock and veterinary doctors of the Indian Army have been very popular; could engagement of veterinary scientists piggyback on the successes of our peacekeepers? How about the defence minister visiting Indian contingents and pushing our geo-political agenda a la George Fernandes, who was the last political executive to have done so three decades back?

The avenues are many—all it requires is a direction from the ‘top’ and a multi-disciplinary and multi-ministerial knocking of heads together. India must definitely transcend from being happy at routine and superficial platitudes being showered on its Blue Berets to being smart in furthering our cause in the tough world of real politik.