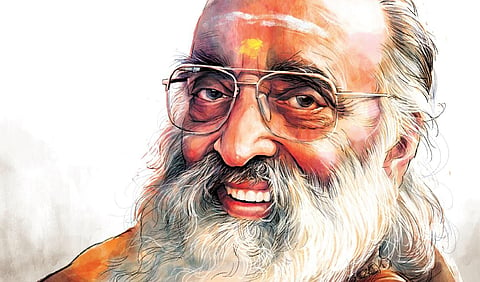

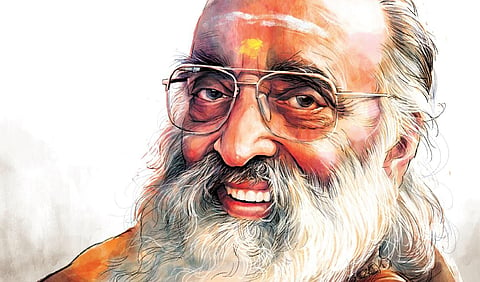

Few in India know that celebrations to mark the 108th birth anniversary of Swami Chinmayananda (1916–1993) commenced on May 8. The numerous programmes and activities to mark this occasion are to continue into 2026, the start of the two-year diamond jubilee commemoration of the Chinmaya Mission, which he founded in 1953. With over 300 centres in more than 25 countries, the Mission is a force to reckon with not only in India but abroad as well. What is its purpose? As Chinmayananda famously said, “Let us convert Hindus to Hinduism, then everything will be all right.”

I was unaware of this significant 108th milestone until I was invited to give a talk on the “Dynamic Silence of Ramana Maharshi” as part of the lecture series organised to mark this event. I immediately agreed although I knew that it would be impossible to do justice to the silence of realisation in any number of words. Dynamic silence, as expounded by the Maharshi, is not the absence of speech or thought, but a state of pure awareness that remains unaffected by the fluctuations of the mind. Maharshi taught that by turning inward through the process of self-enquiry, one could know the Self as oneself.

By going into the very root of the question “Who am I”, the illusion of separation fades away, leading to the direct experience of one’s true nature—the pure consciousness that underlies all existence. This profound realisation brings about a radical shift in perception, allowing one to perceive the world and oneself from a place of clarity, compassion, and unity. As Shankaracharya’s famous Dakshinamurti Stotram puts it: Guro’stu maunam vyaakhyaanam sishyaastu chchinna samshayaah—the Guru’s silent exposition destroys the doubts of the disciples.

Did something similar happen to young Balakrishna Menon—for that was Chinmayananda’s pre-monastic name—in his chance encounter with Ramana Maharshi in 1936? In his own words, “The Maharshi suddenly opened his eyes and looked straight into mine … A mere look, that was all. I felt that the Maharshi was, in that split moment, looking deep into me—and I was sure that he saw all my shallowness, confusions, faithlessness, imperfections, and fears.” Later, reminiscing over this fortuitous encounter in 1982, Chinmayananda said, “Sri Ramana is not a theme for discussion; he is an experience; he is a state of consciousness. Sri Ramana was the highest reality and the cream of all scriptures in the world. He was there for all to see how a Master can live in perfect detachment.”

It is said that fools venture where angels fear to tread. I foolishly accepted the invitation to speak on an unspeakable subject because I felt that the interconnectedness of India’s great modern sages needs to be explored and expounded. In the case of Swami Chinmayananda and Ramana Maharshi, there is also a connection with the order of monks founded by Swami Sivananda, who was the guru of Swami Chinmayananda. It was Swami Chidananda, another disciple of Sivananda, who gave the Ramanasramam president, T N Venkataraman, sannyasa diksha in 1994 (As it happens, Ramanasramam is also celebrating its 100th anniversary this year). As the famous verse from Guru Stotram puts it, the guru principle is one indivisible, all-pervading whole (akhanda mandala karam vyaptam yena cara caram). Even if we see it, because of our identification with our bodies, as manifesting in so many different entities.

But from a mundane point of view, a question does arise. How did a chain-smoking, self-proclaimed atheist become the world-famous proponent and propagator of the message of the Bhagavad Gita and Indian spiritual traditions? That transformation is in itself a remarkable story that exemplifies the profound potential for spiritual awakening within each individual. Menon’s early life as a student activist, colonial prisoner, vagabond, dandy, and journalist with socialist leanings—seemed rather an unlikely prelude to what turned out to be a remarkable career in spiritual, educational, and social leadership.

His encounter with his guru, Swami Sivananda, proved to be a great turning point. It was a couple of months before India’s Independence. Menon, who then worked for National Herald, set out in the summer of 1947 to Rishikesh, determined to check out the claims of the gurus, sanyasis and spiritualists with a critical, journalistic mind. His biographer, Nancy Freeman Patchen, records that Menon’s purpose was far from spiritual: “‘I am going to find out how those holy men are keeping up the bluff! I am prepared to expose the whole racket,’ he declared to his friends.”

Those observing Menon in those days were also confounded: “There did not appear to be a spiritual bone in Menon’s body—he was an extrovert, always on the move, forever talking, constantly drilling everyone as the reporter that he was. They never saw him in a meditative mood; instead, his main interest seemed to be his ever-present cigarette and a cup of tea.” Except for his “big, bulging yogic eyes and extra-long arms,” considered signs of a spiritual propensity, there were no outward signs to indicate a master in the making.

Two years later, on Sivaratri, February 25, 1949—after treks in the Himalayas and reluctant permission granted by his father—Balakrishna was initiated into the ancient order of renunciates and took on the name Chinmayananda. But the task ahead seemed too big to handle. Chinmayananda himself wondered, “Can I do it? Can I face the educated class of India and bring to their faithless hearts at least a ray of understanding of what our wondrous culture stands for?”

On the banks of the Ganga near Rishikesh, Chinmayananda got the answer he was looking for, from Mother Ganga herself: “None could argue against the Eternal Truth that man is in essence God. But could I explain it to others? Sitting, watching the Mother Ganga in her incessant hurry, I seemed to hear the words interlaced in her roar, ‘Son, don’t you see me; born here in the Himalayas, I rush down to the plains, taking with me both life and nourishment to all in my path. Fulfilment of any possession is in sharing it with others.’ I felt encouraged, I felt reinforced. The urge became irresistible!”

The rest, as they say, is history.

Makarand R Paranjape

Professor of English at JNU

(Views are personal)

(Tweets @MakrandParanspe)