Terms such as ‘electoral mandate’ or ‘verdict’ are the most misleading expressions of what we actually deal with in democracies, for they convey the idea that ‘the people’ are in some sense ‘sovereign’ and they periodically elect ‘their’ representatives. The task of the representative in this mythical understanding of democracy is to simply represent and execute the ‘will of people’.

The reality is this mythical ‘people’ does not exist. People are simply the ruled or the governed: subjects of kings in earlier times and other citizens at best in modern democracies. Citizenship is merely the membership of a political community that entitles you to certain rights and is always the attribute of the individual—though occasionally we might loosely talk of communities too as rights-bearing entities.

Democracies relentlessly attempt to reduce populations into passive entities that can be manipulated at will by rulers or demagogues. But the reality, equally, is that the people often play their rulers or prospective rulers too. Democratic politics ties the ruler and the ruled—the ‘people’ and their ‘representative’—in a complex dynamic that results in electoral outcomes which quite often defy descriptions like mandates and verdicts.

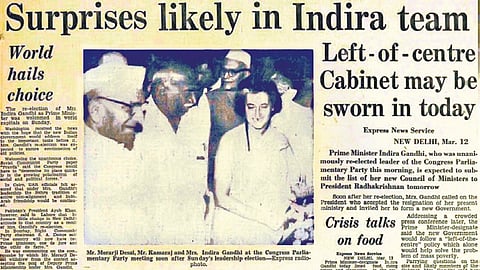

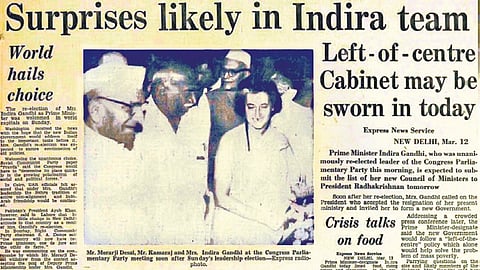

The year 1967 constitutes a turning point in the democratic history of India. That was the time when the giant figure of Jawaharlal Nehru had already passed, as had his successor Lal Bahadur Shastri. Twenty years after independence, the ruling Congress was facing its first major crisis in terms of popular legitimacy and it lost power in nine states. The leadership issue was open at that point.

For the first time since independence, we saw the emergence of a wide array of regional and relatively backward caste parties like the Dravida Munnetra Kazhgham (DMK) in Tamil Nadu, Bharatiya Kranti Dal (BKD) in Uttar Pradesh, and Samyukta Socialist Party (SSP) in ruling coalitions, even if most of them were short-lived. In UP, Charan Singh crossed over to the opposition with many Congress MLAs to become the CM of a non-Congress coalition government. In West Bengal and Kerala, the new coalition governments were dominated by Left parties.

Indira Gandhi was still a novice, who became leader as a compromise between the left and right wings in the Congress. The rise of non-Congress governments, often coalitions with no substantial political vision, demonstrated simply that the old Congress hegemony was collapsing. The outcome was hardly a ‘mandate’—either for any particular party or for any alternative set of policies.

More interesting is the fact that in the next two years, as Indira Gandhi got down to crafting her own political persona, she produced a new configuration in politics with her ‘left turn’. With nationalisation of 14 banks in 1969, followed by abolition of privy purses in 1971 and finally her slogan of ‘Garibi hatao’ in the general elections that year, Indira actually created her own mandate. The people, voting with their feet by deserting the Congress in 1967, had forced Indira Gandhi to take cognisance of the reasons behind popular discontent and come out with a credible programme.

It is another matter, of course, that the new vision that she brought into the party was to remain largely on paper, as powerful vested interests within and outside would ensure that the new vision be subverted. Indira herself might not have wanted to take her own radical rhetoric very seriously beyond a point.

The experience of the first UPA government presents us with a very different picture. Formed after the 2004 elections, the UPA emerged from a constellation of political forces that had worked closely during the preceding six years of NDA rule under Atal Bihari Vajpayee. The Congress, the Left parties and numerous social movements that came together to craft a Common Minimum Programme once again produced a mandate for themselves, with one difference: the programme was the result of years of work on the ground.

It therefore led to enactment of landmark legislations like the Scheduled Tribes (Recognition of Forests Rights) Act, the Right to Information Act and the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, apart from a number of other critical interventions. To be sure, there were other forces at work too within the UPA government that found this orientation inimical to its interests, leading to a wholesale attack on the National Advisory Council that was primarily an advisory body that provided the government a non-bureaucratic feedback channel.

In sharp contrast stands the 2014 election, where the agenda was set up symbolically in the divisive figure of Narendra Modi. Even with formal slogans of vikas or development, most people who voted knew exactly what they were voting for or against. Behind the scenes, as always, were also those who wanted to reverse the changes initiated by the UPA government, especially ones like those embodied in the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act 2013, which had been enacted in response to a major struggle against dispossession. The overt agenda was very different from this covert one. Even though some people may have been led into believing the slogans on development, given the total control of information flows, the core support for the regime came from a series of messages purveyed by the IT cell.

An entirely new definition of ‘the people’ was thus put in place—a people that was called into being through invocation. The ‘mandate’, once again, simply followed.

(Views are personal)

Aditya Nigam | Political theorist formerly with the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Delhi