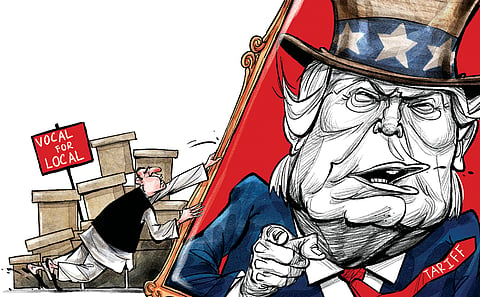

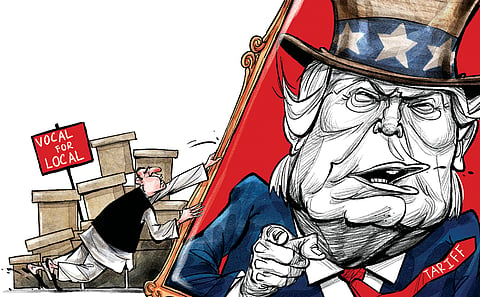

We live in two Indias. They are starkly juxtaposed against each other in situations such as the ongoing tariffs challenge from the US.

Of the two, one India is adept at making a case that this country will fall behind unless it recognises that Donald Trump is not unreasonable in his demand for balanced trade.

This India argues that the Narendra Modi government ought to use Trump’s threat of higher tariffs—at least his initial demands—as an opportunity to usher in the next wave of economic reforms. This India also views Trump’s tariff imposition as a chance to raise this country’s competitiveness in industrial production and other business activities.

The other India is more rooted in the realities of this country, sensitive to the conditions of ordinary Indians. It does not have the tools at its command to make a case that Trump’s actions and behaviour are symptoms of a deep-rooted malaise.

So far at least, Prime Minister Modi has not called the spade in Washington a spade. Lula da Silva, President of Brazil, also facing high tariffs, has said Trump was elected “not to be the emperor of the world”. Modi is still hoping for a trade deal and has been advised by his trusted aides not to escalate matters with the volatile and unpredictable White House.

Hidden behind these symptoms is Trump’s chronic disease, which India must not overlook. At the root of what Trump is seeking is a haughty and imperial imposition on sovereign nations. This disease is not limited to tariffs. He wants to make Canada the 51st US state, take over the Panama Canal and get Denmark to surrender its autonomous island of Greenland to the US.

What if Trump demands one day that in the interest of permanent peace in South Asia, Jammu and Kashmir should be placed under Washington’s trusteeship? Until 1994, when the United Nations Trusteeship Council was wound up, many territories from Tanganyika in Africa to Nauru in Oceania were administered by major powers as they moved step-by-step towards self-government or independence.

It is not inconceivable that in Trump’s view, Jammu and Kashmir fits this bill. After all, he wants to ethnically cleanse Gaza Strip and develop it into a riviera of the Arab world.

As India begins its life under the highest tariffs imposed by the Trump administration, those who are in favour of surrendering to Washington are painting a dismal picture ahead. This India foresees sectors of industry primarily sustained by the American market collapsing, high unemployment in information technology business and a slowdown—if not an end—to business process outsourcing to Bengaluru or Hyderabad.

They insist that the loss of the US market for Indian goods and services cannot be compensated for in the foreseeable future.

There is a sense of déjà vu in this. When India tested nuclear weapons in 1998, triggering automatic sanctions under America’s penal ‘Glenn Amendment’ non-proliferation legislation, one India similarly predicted unimaginable disaster for this country.

They said American sanctions would wipe off much of India’s progress since independence. One newspaper editorialised that India would descend into a dark age. It was a parody of what Jesse Helms, the influential chairman of the Senate foreign relations committee, said about the nuclear tests: “The Indian government has shot itself in the foot. It has most likely shot itself in the head.”

Did India descend into a dark age because Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee sought to assert national power by exercising the country’s nuclear option? Because Vajpayee stood his ground, the US enacted a law 17 months later—the Department of Defense Appropriations Act, 2000—to begin waiving sanctions against India. It led to the most comprehensive review of India-US relations ever between aides to their top leaders: Jaswant Singh and Strobe Talbott.

President Bill Clinton visited India in 2000, the first such presidential visit in 22 years. The two countries have not looked back—until now, that is. For those Indians who are now campaigning for surrendering to Trump, the twists and turns in India-US relations during the two years following the nuclear tests will be instructive.

There is a similar earlier history that is worth recalling now. In 1989, President George H W Bush’s administration invoked America’s Trade and Competitiveness Act to threaten action against India for its high duties and closed markets—exactly the same complaints that are now being voiced by Trump.

That story had a different ending than the nuclear tests episode. Bush Senior’s threats—known as Super 301 actions after the relevant section of US legislation—dragged on for over a year.

Then India went into a severe economic crisis, which had nothing to do with the US threats. After the country’s gold reserves were pledged abroad, newly elected Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao initiated his vaunted economic reforms in 1991.

The reforms, inter alia, addressed many of America’s concerns and the Super 301 threat lost its relevance and vanished.

True, the current state of geoeconomics is vastly different from 1989 or 1998. The world is more integrated and supply chains are more global than ever. An entire generation has grown up in India used to greater prosperity and open doors for easier migration to richer nations.

The clamour for compromise with Trump is a weakness, not a sign of strength in being the fourth largest economy in the world in GDP terms. It is an excuse to avoid pain today, forgetting that national achievements without struggles are bound to be ephemeral.

India has strengths that can alleviate the pain of Trump’s tariffs, although avoiding pain altogether is not an option. What is needed now is a sense of business confidence and national purpose. Gleaming Samsung factories, iPhone assembly plants and Japanese industrial townships have obscured a burst of small entrepreneurship in aspirational blocks across India.

Several districts in India have now adopted an innovative ‘One District, One Product’ scheme and are nurturing micro enterprises in various sectors. The national media has mostly ignored that ‘vocal for local’ is not a mere slogan.

Markets like Dubai are proof of this new trend. These are pain relievers. Ultimately, a trade deal will have to be negotiated with America, but not one dictated to New Delhi from Washington.

K P Nayar | Strategic analyst

(Views are personal)