A few years back, a Hindi teacher at Moscow University told me to convey her gratitude to Prime Minister Narendra Modi. “Since your PM speaks only in Hindi, instead of English, to interpreters while in Russia, a Hindi-to-Russian interpreter like me is now in demand,” she explained.

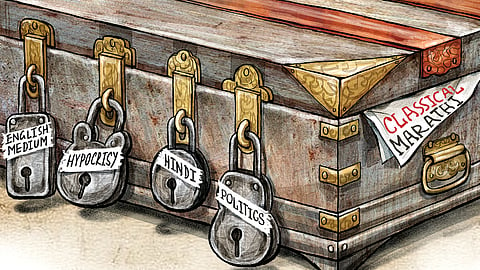

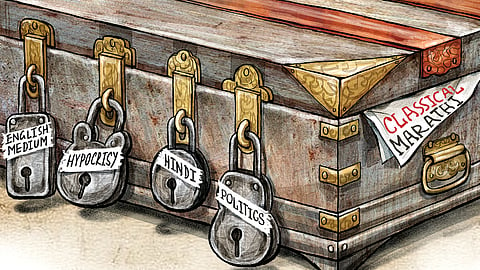

The moral of this story is that expanding the sphere of any language’s application is a must to create a market for it. At a time Maharashtra politics is once again being stirred by the language issue, not just the Thackeray brothers, but many others in the state are missing this point.

Marathi was recently—and very rightly—recognised as a classical language. Classical languages are defined as ‘ancient languages with independent traditions and a rich literary history that continue to influence various literary styles and philosophical texts’. After Tamil, Sanskrit, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam and Odia, Marathi as well Pali, Prakrit, Assamese and Bengali have now become classical languages of India.

A high level of antiquity, the presence of a significant body of ancient literature preserved for generations, originality and distinctness of modern forms are the established criteria for granting the ‘classical language’ tag. Obviously, Marathi fulfilled all these requirements. However, getting the classical language tag doesn’t change the ground situation.

The Maharashtra government’s proposal to introduce Hindi as one of the three languages to be taught under the three-language formula had nothing against Marathi. In no way would it have damaged the future of Marathi. It could be that the Thackeray brothers conveniently used it to mobilise public opinion. But on the ground, three things are clear.

First, exploiting the issue of Marathi versus Hindi will certainly not help the cause of Marathi. Second, it may not help the Thackeray cousins revive their electoral prospects. And third, it may not seriously dent the support base of the Mahayuti government.

No doubt, in Maharashtra the prominence of the Marathi language cannot and should not be undermined at any cost. The three-language formula has been there for decades and many of my generation in the state learnt Hindi from the fifth standard. However, in the context of the recently-manufactured controversy, Marathi lovers would do well to be mindful of certain key factors.

The first and foremost is that the prestige of any language depends on whether its native speakers take pride in speaking it in public. Today, in Mumbai, many Marathi-speaking people routinely use either Hindi or English even while conversing with their Marathi-speaking friends.

One of the many reasons for this strange behaviour is that somewhere deep in their minds, there is a feeling that speaking in Hindi or English adds to their dignity, as against their own mother-tongue. The impact of this complex is so grave that most Marathi-medium schools in Mumbai are on the verge of extinction.

Can one blame Hindi-speaking Maharashtrians for this? Again, unlike in Chennai or Kolkata, in Mumbai, outsiders feel more at home as they can do very well without any working knowledge of Marathi. The Marathi theatre is known for its vibrancy and has a rich tradition. And yet, Marathi plays or movies hardly find a place in non-Marathi newspapers because most English and Hindi newspapers in Mumbai don’t feel the need to have Marathi-speaking mediapersons among their staff. Unless the Marathi language and culture makes a powerful entry into the ethos of the non-Marathi people, Marathi cannot grow.

The next important factor is the element of hypocrisy inherent to the conduct of the so-called saviours of Marathi. The Thackerays see no contradiction in the fact that while they advocate the use of Marathi from the rooftop, they don’t mind not learning in Marathi medium. They fail to understand that language is the vehicle of culture and the medium of instruction in your school helps or harms the cause of not just your mother tongue, but also your mother culture.

To understand the meaning of a proverb in a particular language, one at times also has to scan through the history of the region where the respective language flourished. Today, many Marathi-speaking persons working in Marathi print and electronic media cannot speak their mother tongue without mixing Hindi and English terms. They don’t understand that this adulteration of Marathi hampers its evolution as a knowledge-medium. After Veer Savarkar, rarely a public leader or a journalist has taken pains to evolve new coinages for emerging concepts in Marathi.

Hypocrisy is also evident in the fact that those who are today opposing Hindi had extended a red-carpet welcome to English when it was introduced right from the first standard way back in 2001. Further, in 2006, the then Congress government had defended its decision to introduce a full-length, 100-mark examination of English language skills right from the first standard. Clearly, it was a market-friendly decision and those opposing the teaching of Hindi today were silent when English was in a way ‘imposed’ on the students at such an early age.

All in all, while the cause of the Marathi language needs to be taken up by all who live in Maharashtra,and not just those who have Marathi as their mother tongue. Whipping up an anti-Hindi sentiment is neither relevant nor acceptable. If learning English empowers one to tap global opportunities, learning Hindi has the potential to open up pan-India opportunities.

If Marathi is to gain strength, creating a market for it is the only effective way. While the state language must get state patronage, the public’s patronage is even more critical. Hindi is the official language in nine states. Besides, in states like Odisha, West Bengal, Assam, Telangana and even Gujarat, people prefer to speak in Hindi than in English when they interact with an outsider. In many Northeastern states, Hindi is slowly replacing Assamese.

Non-Marathi speakers definitely should long for learning Marathi and understand its culture comprehensively. But the prerequisite of their longing is generating a sense of belonging towards all that represents Maharashtra—not just language, but food culture, music, theatre and cinema too. And for that, the onus has to be shared by both Marathis and non-Marathis.

Vinay Sahasrabuddhe

(Views are personal)

(vinays57@gmail.com)