A ceasefire in Ukraine is of personal interest to almost half the world’s people—not only for geopolitical reasons, but because the origin of the Indo-European languages has been traced to its battlefields. Hundreds of Ukraine’s culturally significant sites have been endangered by the war and thousands of archaeological artefacts have vanished into Russia. The loot of prehistory is a faithful companion of war, but this case is special, because it concerns the Holy Grail of philology, the search for the origins of the vast Indo-European family of languages and communities.

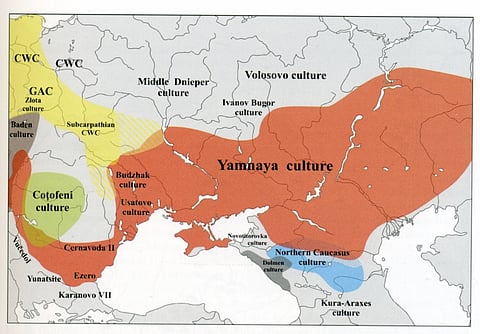

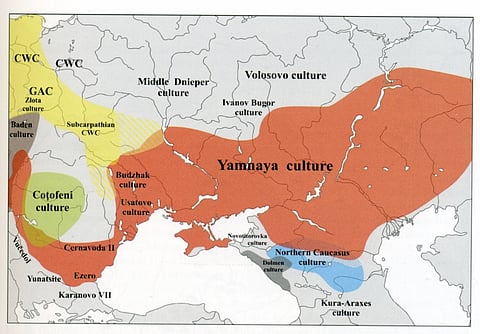

Earlier this month, researchers at Harvard Medical School mapped ancient genetic data to archaeological finds and linguistic history, and established that proto-Indo-European, a lost parent language which exists only in reconstruction, originated in a Russian-occupied region of Ukraine. Kherson Oblast seems to be the point of origin from where cultures identified with cattle herding and chariots spread across the Old World.

Genetic data supports the theory of the steppe origin of Indo-European groups, suggested by the German philologist Otto Schrader in the 19th century and the Australian archaeologist V Gordon Childe between the world wars, and developed into the ‘kurgan hypothesis’ (kurgan is Turkic for ‘burial mound’) by the Lithuanian archaeologist Marija Gimbutas in the 1950s. One Kurgan community, the Yamnaya culture, is now the focus. The very name shows how close the Indo-European languages are. It derives from yama, which means a burial pit in Russian and Ukrainian. Across most of South Asia, it is the name of the god of death himself.

Max Müller would have called these closely-related cultures ‘Aryan’, but that term has become loaded by generations of racist politics in Europe and South Asia. But Müller believed that Aryans formed a linguistic category, not a racial one. Present thinking retains that line―the title of the most recent major work on the subject is David W Anthony’s The Horse, the Wheel and Language.

While a ceasefire in Ukraine would pause the organised loot of archaeological sites, Russia may contest Ukraine’s right to be regarded as the original homeland of Indo-European speakers. It’s a long-running battle for cultural supremacy. Russia has come to signify a political and cultural territory controlled by Moscow, but the Kievan Rus, a mostly eastern Slavic coalition, ruled from Kyiv from the 9th century, was about 400 years older than Muscovy. Kyiv developed the basis of many features of Russian culture, from religious architecture to the Russkaya Pravda, the statute book which started Russia’s legal traditions. Now, the two countries have something much older and more valuable to fight over—the cultural origins of half the world.

The Ukraine war is one of several recent events which remind us that so long after the destruction of the libraries of Alexandria, Persepolis and Nalanda, the archive remains under threat. Conflict remains the biggest threat to museums, as in the systematic destruction of the pre-Islamic record in Taliban Afghanistan and the looting of the Egyptian Museum of Antiquities on Tahrir Square in Cairo during Arab Spring. After the fall of Saddam Hussein’s government, not only was the National Museum of Iraq looted, but the robbers conducted their own excavations across the Fertile Crescent and thousands of artefacts disappeared. The part of the archive of human civilisation that remains underground is at the greatest risk in volatile times.

Meanwhile, digital technology has broadened and deepened the capacity and accessibility of the archive. But its record is far more fragile than the brick-and-mortar museum. This is becoming obvious as the government, academia and other institutions in the US expunge content associated with ‘wokeness’. Entire websites have gone offline and thousands of pages, reference material for the administration of subjects from immigration to medicine, have been pulled down. Doctors want to know how they can write research material about, say, ovarian cancer, without referring to ‘women’ and ‘gender’—words whose use is now discouraged.

Military history could be purged of references to people named Gay, a surname derived from the Medieval French gai. People with that surname are being identified, but the prize target is Enola Gay, the ‘superfortress’ that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. The pilot had named it after his mother, a strange choice for a machine built to deliver death.

Eliding history would make room for interest groups looking to rewrite history, further reducing the credibility of records that are already compromised by reckless publishing. Retraction Watch, which tracks academic mea culpas, reports that five papers by a French academic infamous for a field study on ‘bust size and hitchhiking’ are being dropped. A Pakistani scientist whose work was rejected by a journal found it published elsewhere by a professor in Bengaluru. And multiple instances of the peculiar phrase ‘vegetative electron microscopy’ in learned papers were traced to faulty scanning and machine translation of a Farsi original. These cases illustrate how easy technology has made it to poison the well of knowledge.

The removal of politically-targeted words is blurring the line between truth and falsehood. The way forward is to maintain a healthy scepticism while remaining mindful of the motto of Mehitabel the alley cat, as reported by Archy the free-versifying cockroach in Don Marquis’s classic Archy and Mehitabel: “Toujours gai, toujours gai (Always cheerful, always cheerful).”

(Views are personal)

(Tweets @pratik_k)

Pratik Kanjilal | Senior Fellow, Henry J Leir Institute of Migration and Human Security, Fletcher School, Tufts University